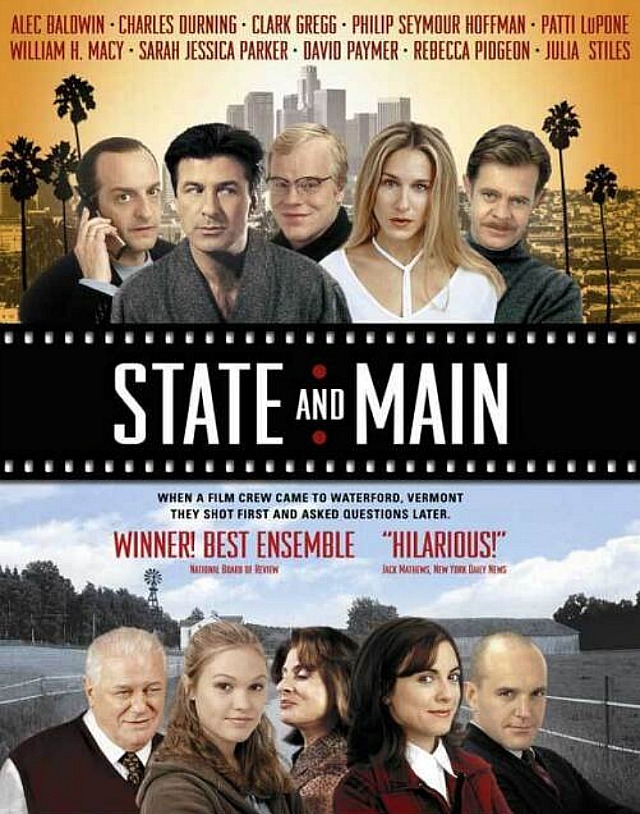

David Mamet‘s State and Main, a critically approved culture-clash satire, opened nearly 20 years ago. It’s about character issues (morality, honesty, “purity”) that arise in a small Vermont town during the location filming of a Hollywood movie called The Old Mill. It’s actually more about the townspeople being co-opted by Hollywood opportunism and amorality than a “clash” of values, although a divide between some of the characters is eventually exposed.

All Mamet plays and films are written in Mamet-speak (short staccato sentences, a tone of flat irony, not much in the way of natural-feeling interplay), and the more strictly this is adhered to the better they work. That said, Mamet material has always played better on stage. I still maintain that the 1984 Broadway production of Glengarry Glen Ross (which I attended on opening night — 3.25.84 at the John Golden Theatre) was the most perfect Mamet experience anyone has ever savored.

In any event I recall being half-amused and half-annoyed by the Mamet-speak in State and Main, but mostly tolerating it. And yet for years I’ve told myself that the only truly luscious line was Alec Baldwin‘s “heh…so that happened!” after he crawls out of an overturned station wagon. I actually adopted it as one of my fall-backs whenever some calamity or misfortune occurs. I use it to this day.

So last night I re-watched State and Main on Amazon to see if there were other great lines that I’d forgotten. And there aren’t — the Baldwin is still the only keeper.

And while Mamet is castigating Hollywood boy’s club sexism, particularly in the matters of Baldwin’s Polanski-like yen for teenage girls and the ruthless pressure that Sarah Jessica Parker‘s actress character endures when she decides not to perform a nude scene unless her fee is upped by $800K, the film feels callous in this post-#MeToo realm. “It hasn’t aged well” is putting it mildly.

And Phillip Seymour Hoffman‘s screenwriter character behaves like a submental Boy Scout dingbat dweeb. He’s a published playwright who’s attracted to fetching, intelligent women (he falls for small-town book seller Rebecca Pidgeon) and, being a writer of some perception, is presumably aware that Hollywood is a culture defined by big money and moral relativism. And yet he goes simple when asked to testify about whether Julia Stiles (who was 18 when State and Main was filmed and looks no younger than that) was in the car with Baldwin when it crashed. She was but so what? And yet if he tells the truth he’ll be blackballed by the industry, and if he doesn’t his soul will be forever soiled.

Then again Hoffman isn’t an eight year old — he’s a 30something adult in bed with reptiles. With the film company having been forced to leave a previous New England location because of another young girl episode, Hoffman is fully aware that Baldwin’s “hobby” (i.e., seducing teens) is a fixed feature. And it’s not as if Stiles is a wrecked victim accusing Baldwin of sexual assault — she clearly schemed to bed him and got what she wanted without much effort.

So a morally unsavory episode happened, but no actual crime was committed. (The age of consent in Vermont is 16.) So if Hoffman is any kind of realistic Hollywood careerist, he has to somehow wiggle out of testifying. Or he has to develop amnesia. It’s how this industry has dealt with embarassing episodes (including incorrect sexual dalliances and car accidents) for many decades, and unless Hoffman is ready to commit career suicide (not an attractive trait) he has to somehow slither out of this.

The way to avoid embarassment all around, obviously, would be for Hoffman to go to William H. Macy‘s director or David Paymer‘s studio chief and urge them to keep Stiles quiet by paying her off. A $50K college fund, let’s say. But they don’t pay Stiles off, and before you know it a local attorney (Clark Gregg) is threatening the movie company with some kind of sexual assault lawsuit and so they have to pay him off with a $300K bribe, which he will use for a forthcoming Congressional campaign. Brilliant!

So with Hoffman playing a starry-eyed idiot there’s no one to identity with or root for, and so I didn’t care about anyone in State and Main…not really. And so it isn’t a comforting or satisfying moral fable. It just feels precious.