I got into a disagreement with a fellow columnist after last week’s screening of John Patrick Shanley‘s Doubt. He didn’t have a problem with the acting or the writing or the general thrust of it, even, but he felt it “wasn’t visual enough.” I gathered that he wanted to see Doubt meets Children of Men. Something swoopier, fiercer, crazier…whatever.

The irony for me is that the visual delivery in this film (and I don’t just mean the beautifully muted fall-winter colors in Roger Deakins‘ cinematography) is just right. Shanley’s direction serves the holy grail of the text and lets the performers — Meryl Streep, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Viola Davis, Amy Adams — do their stuff. They do that and more. And when it’s over you know you’ve bitten into something, or it’s bitten into you.

There’s so much to be said for a contained and compressed high-pedigree drama that does exactly what it intends to do, and is very content with this. A film without lunging, stumbles or missteps. Doubt doesn’t waste a frame or a line or a single shot, and it leaves you hanging in just the right way. That is to say it disturbs and agitates without resorting to easy catharsis. A play this well served isn’t just a play well served. It morphs into something else — a dramatic life form of its own.

This is why I feel it’s Best Picture material. The chops and the content serve the whole and vice versa. And, like I said last week, when you throw in Deakins’ cinematography it’s even more of a feat. Doubt is a smallish film — a story about ambiguity and uncertainty among a small group of people in two or three rooms with a hallway and a park thrown in — that acts and in fact becomes “big” because of its sharpness and discipline. There’s really no way to assail it that cuts any ice with me.

Todd McCarthy‘s Variety review aside, I loved Streep’s performance as Sister Aloysius Beauvier. She’s the very model of a pinched and joyless crone, an old- school harridan with a habit — the kind of nun that used to try and “beat an education” into Marlon Brando‘s Terry Malloy. The fact that she’s a kind of mythical beast and that Streep is expert at letting you know precisely what’s going on in her hard and damning head is, for me, a trip. She’s almost Mommie Dearest, and I mean that as a genuine compliment.

If I still got high I would get royally blitzed next month and go see Doubt with friends and quietly chuckle at every gesture.

And I don’t mean she tries for comedy. The genius of Streep’s performance is that you can take her work as dead straight drama component or a hoot, depending on your mood or attitude. What counts is that you can sit there and read her each and every second. There’s never any doubt what she’s thinking, intuiting, suspecting.

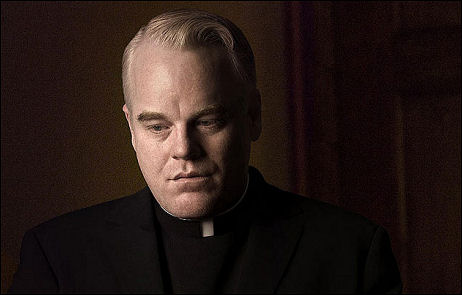

Set in the Bronx in 1964, inside a grim Catholic school called St. Nicholas, Shanley’s play is basically about Sister Beauvier’s growing suspicions that Father Flynn (Hoffman) has gotten a bit too intimate — perhaps more than that — with an African-American altar boy named Donald (Joseph Foster II).

But it’s not just an “is he or isn’t he?” thing. Shanley’s play is clean and precise in the way the themes of the piece are made unmistakable from the get-go. “What do you do when you’re not sure?” Flynn asks in his opening-scene sermon. And yet Streep is sure — she doesn’t allow for any overt uncertainty because she damn well knows. And she may be right, we come to realize as things move along.

But is she in fact that? Is Hoffman’s priest a born diddler — a Johnson-era manifestation of a malignancy that has turned the Catholic church’s rep into a sick joke over the last decade or two? Or is he being steamrolled to some extent? Or maybe a little bit, at least?

Doubt‘s dramatic peak comes when Sister Aloysius has a frank conversation with Donald’s mom (Davis) about what may in fact be going on. The scene is harrowing because of what Davis does with it. Streep pretty much listens and reacts and slowly becomes more and more appalled as she considers the mother’s rationalizations — her fear of going into this realm, knowing or believing as she does that it’s not Father Flynn as much as…well, let’s not spoil.

The scene lasts only ten or twelve minutes, but Davis’ performance is Beatrice Straight great — and if you have to ask what that means, forget it. It’s a bulls-eye performance that everyone but everyone is going to have to acknowledge.

Hoffman’s Flynn delivers…how to say it? A pervy but earnest ambiguity. Your gut tells you he’s probably a pederast, certainly in terms of latent desire, but at the same time something tells you he may not quite be. He may finally be a straddler, and that in itself is not a punishable offense.

Adams plays a kindly young nun who senses the undercurrents and cross-currents as clearly as Streep does, but whose function is mainly to emotionally telegraph all this to the slower folks in the audience.

There’s no coming out of Doubt and going “meh.” There’s nothing amiss about any of it. Okay, it’s not madly David Fincher or Alfonso Cuaron but it is like a kind of perfect moral swiss watch, and such things are very hard to sculpt in just the right way. Anyone who sees it and shrugs is looking into some kind of cavern of their own soul. Every move is nailed down tight in this thing. And class, focus and discipline can’t be faked. Either a film has these things in abundance or it doesn’t. There’s no ambiguity here.