“Sometimes of course I have failed. Tippi Hedren did not have the volcano”. — Alfred Hitchcock quoted on 5.28.66 by the El Paso Herald-Post, and re-quoted on page 649 of Patrick McGilligan‘s “Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light.”

There’s an old saying that goes “never trust the artist — trust the tale.” I can imagine Marnie defenders using this to justify their belief that Hitchcock made a better film than even he himself realized. But that’s a stretch, I think. When an esteemed director who was entirely candid with Francois Truffaut about every film in his storied career turns around and says “this movie didn’t work because the lead actress wasn’t sexy enough,” it’s hard to call him deluded. Failure is never easy to admit to but Hitchcock, to his credit, did so.

The quote is even more fascinating when you consider that it was Hitchcock and not Hedren who “had the volcano” (i.e., was burning with sexual current) during the filming of Marnie and, I’m sure, during the filming of The Birds. This feeds into my theory (posted in a piece that appeared on 4.16.15) about why Marnie feels fake, flat and strained. It was, I supposed, because Hitchcock “was emotionally off-balance, torn between his secretive lust and his often dazzling directorial technique, when he shot it. I’m sure he thought he knew what he was doing when he made Marnie, but deep down I don’t think he knew which end was up. The much-written-about fact that he was invested with ‘having’ Hedren means that he must have felt enraged and probably disoriented when he realized his efforts wouldn’t come to anything.”

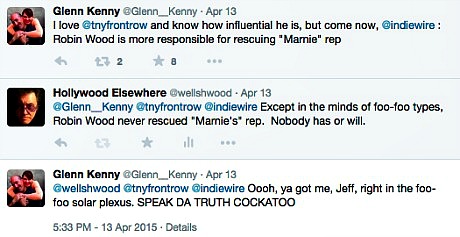

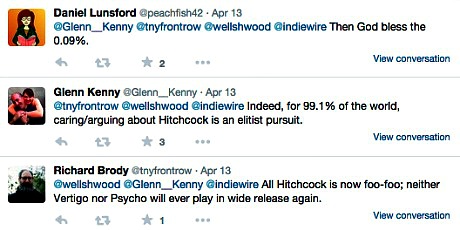

In any case I felt hugely dispirited this morning when I read a 7.20 BBC Culture poll that ranked Marnie as #47 among the 100 Greatest American Films of all time. Hitchcock’s Psycho is ranked #8 (fine) but why is Marnie ranked 47th instead of the far more brilliant and deserving Strangers on a Train, North by Northwest, Rear Window or Shadow of a Doubt? The main reason, I said this morning, is due to the fervent efforts of “a small, tightly-knit fraternity of hardcore Marnie dweebs” (Richard Brody, Glenn Kenny, Dave Kehr and two or three others) “who’ve been beating the drum for years.”

This remark inspired HE commenter “brenkilco” to joke that this determined fraternity is “insidious and frightening…they’re just like ISIS except instead of beheading people they like Marnie.” This inspired “Duke Savoy” to add, “Sort of a spiritual decapitation.”

I laughed along with everyone else, but the ISIS analogy inspired a thought. Many have noted that the ISIS army numbers only about 20,000 so why don’t U.N. forces just go into Iraq and Syria and wipe ’em out? By the same token there are…what, less than ten serious, credentialed, name-brand critics who are staunch Marnie devotees? Why don’t the legions of Marnie haters just go after them and rhetorically surround them like Santa Anna’s forces surrounded the Alamo and stop this “Marnie is a masterpiece” crap once and for all?

I’ll start things off with a partial reposting my three-month-old piece, “Don’t Marnie Me”:

“The vast majority of Hitchcock fans…regard Marnie as an intermittently interesting but mostly dull and actually quite grotesque film for the most part — Hitchcock’s first major misfire since Under Capricorn and perhaps even his all-time worst movie. Even the sometimes awful Torn Curtain, which I had trouble re-watching when the Hitchcock Bluray box set came out two or three years ago, is better than Marnie.

“The Birds was the end of Hitchcock’s glorious 14-year run which began with 1951’s Strangers on a Train — Marnie signalled the beginning of the downturn.

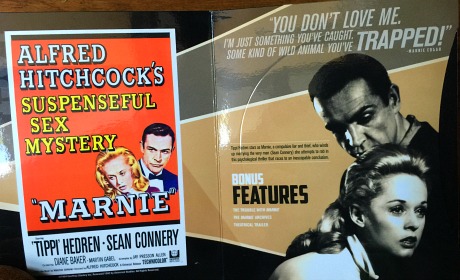

“Marnie is plagued by an initially intriguing but finally quite dull lead character (augmented by a chilly, constipated performance by Hedren), and by oppressively slow pacing, expositional on-the-nose dialogue, a tedious psychological scheme and some truly atrocious visual effects (hokey matte paintings, gruesome rear-screen projections and some kind of sexual or menstrual bloodbucket freak-out effect that has to be seen to be believed).

“A drama about the fetishy manipulation of a somewhat icy, psychologically screwed-up femme fatale, Marnie was as much of a ‘personal’ Hitchcock film as Vertigo (’58), which dealt with similar characters and themes. Marnie‘s basic story, about a frigid kleptomaniac (Tippi Hedren ) being blackmailed into sex and marriage by an ex-boss (Sean Connery ), reflected Hitchcock’s relationship with Hedren, whom he groomed and controlled and tried to sexually access between the making of The Birds and Marnie in late ’62, ’63 and ’64.

“Sean Connery‘s Mark Rutland, obsessed with Hedren’s Marnie, uses the threat of informing the authorities about her larcenous history to force her to marry him, even though he also has a semblance of tender feelings for her, just as Hitchcock allegedly threatened to torpedo Hedren’s career if she didn’t put out.

“Hitchcock worshipper Robin Wood, who died in ’09, made one of his points on “The Trouble With Marnie,” a 2000 Laurent Bouzereau documentary contained on the Bluray.

Wood claimed that Marnie‘s ludicrous visual effects ‘can be defended if one notes the roots of the film in German Expressionism,’ according to the Marnie Wiki page.

“‘Very early on when he started making films, [Hitchcock] saw Fritz Lang‘s German silent films, [and] was enormously influenced by that, and Marnie is basically an expressionist film in many ways,” Wood wrote. “Things like scarlet suffusions over the screen, back-projection and backdrops, artificial-looking thunderstorms — these are expressionist devices and one has to accept them. If one doesn’t accept them then one doesn’t understand and can’t possibly like Hitchcock.’

“Except before Marnie Hitchcock never went all German expressionist on his audience. With pretty much every film from The Birds on back to his 1920s and ’30s British period, everything he shot was more or less in the language of “realism,” or at least realism as far as he (or the technology of the day) was able to reconstruct it. Not 100% strict docu-realism, of course, as there was always a certain visual flourish or a touch of impressionism in every Hitchcock film, but close enough.

“I think Hitch allowed the influences of Fritz Lang to run the show when he was shooting and cutting Marnie in order to convey what must have felt to him like an unreal emotional episode — pining for an icy blonde actress who wouldn’t even give him a handjob and going half-crazy because of this…a world-class director reduced to the status of rejected schoolboy or, worse, that of a dirty old man who had failed to behave in an appropriate manner.”