[Partly borrowed from “Peak Years“, posted on 3.11.13]:

Which present-tense, brand-name directors are peaking right now? In 2024, I mean. Generally speaking peak director runs last around ten years, sometimes a bit longer. You would think 15 or 20 or even 25 years would be closer to the norm, but I’m not talking about mere productivity or financial success — I’m talking about peak years, great years.

Two things have to happen for a director to enjoy a special inspirational run. One, he/she has to be firing on all cylinders — adventurous attitude, good health, relentless energy. And two, the culture has to embrace and celebrate his/her output during this run of inspiration.

Just being a gifted filmmaker doesn’t cut it in itself — the public (or at the very least the critics and the award-bestowing fraternity) also has to agree.

David Lean had a high-quality ten-year run run from Brief Encounter (’45) through Summertime (’55), but his prime-zeitgeist period lasted only eight years — The Bridge on the River Kwai (’57) to Dr. Zhivago (’65). The poorly received Ryan’s Daughter nearly finished him off, but then he came back in ’84 with A Passage to India.

John Ford‘s zeitgeist decade ran from The Informer (’35) to My Darling Clementine (’46), then he began to caricature himself with his Monument Valley western films of the late ’40s and ’50s. Ford then resurged with The Horse Soldiers (’59) and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (’62).

Alfred Hitchcock did superb work in the ’30s and ’40s, but his window of mythic greatness lasted only nine years — Strangers on a Train (’51) to Psycho (’60).

Billy Wilder‘s grace period ran ten years — Sunset Boulevard (’50) to The Apartment (’60).

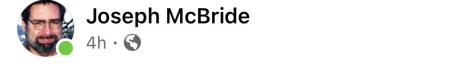

Francis Coppola‘s window ran from The Godfather (’72) to One From The Heart (’82).

Oliver Stone had a 13-year window — Salvador (’86) to Any Given Sunday (’99).

So far [written in ’13] Alejandro Gonzales Inarritu has had a decade-long grace period — Amores perros (’00) to Biutiful (’10).

David Fincher has enjoyed an eleven-year window so far — Fight Club (’99) to The Social Network (’10).

In HE’s book Geta Gerwig is cuurently peaking, obviously, although the prospect of her making a Narnia film depresses me. Todd Phillips, who pole-vaulted up to a new level with 2019’s Joker and appears to have a slam=bang sequel with Joker: Folie a Deux, is peaking bigtime as we speak. Who else?

In an 11.1.11 interview with N.Y. Times columnist Frank Bruni, Alexander Payne, who’d recenty turned 50, admitted that he’d made too few movies up to that point, and that he intended to pick up the pace.

“I’m in my prime right now,” Payne said. “I still have energy and some degree of youth, which is what a filmmaker needs.”

Is Payne concerned about using it before losing it? “Oh yeah,” he said. “Big time. You look at how many years you have left, and you start to think: How many more films do I have in me?”

He mentioned, for the second time in our talks, that Luis Buñuel didn’t really get going until he was in his late 40s. That consoles him. The Descendants, then, isn’t just a movie. It’s a marker, a dividing line between his slowly assembled oeuvre until now, including Election (1999) and About Schmidt (2002), and the intended sprint ahead.

“I want to move quickly,” he said, “between 50 and 75.”

On the other hand Andrew Sarris‘s remark about artists having only so much psychic essence (i.e., when the cup has been emptied, there’s no re-filling it) also applies.

Sidenote: While I did pretty well as a journalist and a columnist in the ’90s and early aughts, my big decade began in ’06 when I took HE in to a several-posts-per-day bloggy-blog format. Everything was pretty great for 13 years until the wokester zealots ganged up on me in ’19 and ’20.