The Hollywood Reporter‘s Kirk Honeycutt has huffed and puffed and unequivocally panned Rob Marshall‘s Nine (Weinstein Co., 12.18). And Variety‘s Todd McCarthy, playing it cooler and more circumspect. has given it a friendly and approving pat on the back.

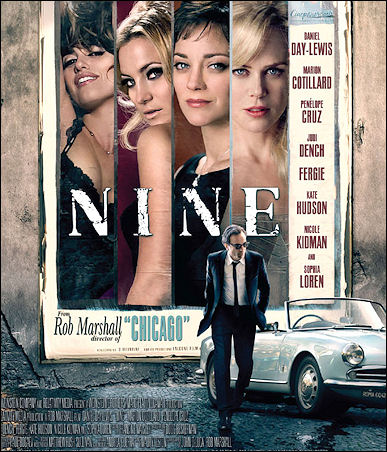

Nicole Kidman, Daniel Day Lewis in Rob Marshall’s

Nine.

And yet between the lines you can sense an absence of serious gushing pleasure in McCarthy’s reactions. The ultimate effect is that his review doesn’t really counter-balance Honeycutt’s, which is much more impassioned. What Nine needs now is a champion — an advocate to ride in on a white horse with wings (like the TriStar horse) and write something about Nine that’s not just knowing and supportive but operatic. An orgasm review that gets high off its own juices…anyone?

“The Nine disappointments are many,” grumbles Honeycutt, “from a starry cast the film ill uses to flat musical numbers that never fully integrate into the dramatic story. The only easy prediction is that Nine is not going to revive the slumbering musical film genre. Box-office looks problematic too, but moviegoers are going to be enticed by that cast, and the Weinstein brothers certainly know how to promote a movie. So modest returns are the most optimistic possibility.

“Federico Fellini‘s 1963 masterpiece takes you inside a man’s head. Since he happens to be a movie director, those daydreams and recollections are visually striking but, more to the point, you sense, through the nightmares of an artist blocked from his own creativity, everything that is going on inside this man. In Nine, written by Michael Tolkin and the late Anthony Minghella, you get a tired filmmaker with too many women in his life and not enough movie ideas.

“Daniel Day-Lewis plays Guido and, to his credit, it’s not Marcello Mastroianni‘s Guido but a new character, more burnt-out than blocked and increasingly sickened by his womanizing. He’s an incredibly sexy man and performs all the right moves. The problem is he keeps doing those moves over and over so you experience not so much artistic angst but a guy trying to sober up from a two-week binge. Sporting a scruffy beard and running a hand through long hair only goes so far.

Penelope Cruz, Daniel Day Lewis.

“With Nine you never get inside the protagonist’s head. You just can’t decide whether his problem is too many women or too many musical numbers breaking out for no reason.”

McCarthy finds not just reason but rhyme. “Cutting between black-and-white and color in the musical numbers and, like Fellini’s film, constantly on the move as Guido is buffeted about with scarcely a moment to breathe, much less write a script, Nine takes the the matter of directile dysfunction seriously without being pretentious about it,” he writes.

Michael Tolkin and Anthony Minghella‘s script “notably finds a way to honor 8 1/2 while enabling one to put it to the side of one’s mind, and in illuminating Guido’s folly while still taking seriously his relationships with women.

“Instead of making Guido entirely self-absorbed and self-serious, Day-Lewis at once places the viewer firmly in the palm of his hand and then in his pocket by emphasizing the character’s humorous awareness of his position in life. He puts on a grand show at a press conference, although one journalist, noting that Guido’s last two films flopped, pierces the armor of jokiness by asking, ‘Have you run out of things to say?'”

Which instantly recalls a Randy Newman lyric from a few years ago: “I got nothin’ left to say / “I’m gonna say it anyway.”