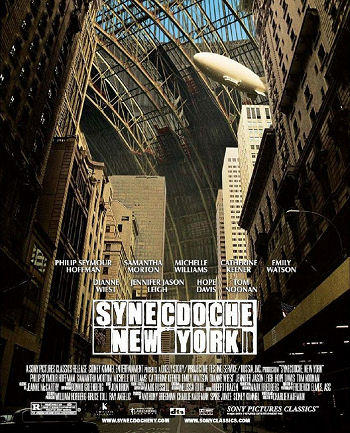

Charlie Kaufman‘s Synecdoche, New York opens limited today. But before getting into my own complex, semi-enthused, slightly tortured feelings about this undeniably interesting, densely layered film, let me quote one of the greatest opening paragraphs of a N.Y. Times film review that I’ve ever read, written by Manohla Dargis and concerning, naturally, the matter at hand:

“To say that Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York is one of the best films of the year or even one closest to my heart is such a pathetic response to its soaring ambition that I might as well pack it in right now. That at least would be an appropriate response to a film about failure, about the struggle to make your mark in a world filled with people who are more gifted, beautiful, glamorous and desirable than the rest of us — we who are crippled by narcissistic inadequacy, yes, of course, but also by real horror, by zits, flab and the cancer that we know (we know!) is eating away at us and leaving us no choice but to lie down and die.”

That, ladies and germs, is what writing can be, needs to be, should be, and damn well ought to be at times. Perhaps even often.

But back to my own reaction, which I posted on the morning of Tuesday, 5.26, or four days after I saw it in Cannes, sitting in a sixth-floor studio apartment in the Montparnasse section of Paris. It was a partly…okay, 60% negative response, but I didn’t intend to come down on the film in a scolding way, given that I enjoyed and even relished it in many respects.

To illustrate this point, here are three graphs (composed of this and that sentence rescrambled for maximum effect) from the original review:

Untitled from Hollywood Elsewhere on Vimeo

“I loved it in portions, understood the point of it, and was intrigued and somewhat amused by in the early rounds. An imaginative Alice in Wonderland-type thing, it has rich ideas and a certain fully worked-out totality. It is clearly smart-guy material, wise and witty, at times almost elevating, at times surreal, and with performances that strike the chords just so.

“I was especially wowed by a sermon scene that happens sometime in the last third. It’s just some young bearded clerical letting go with the gospel according to Kaufman (we live in a gloomy, fearful universe), but the way it was written and performed made me feel alive and re-engaged. It encapsulates what’s really good and special about the film.

“I was never exactly bored. In a way it’s a riff on Federico Fellini‘s 8 and 1/2. It’s been 45 years since that landmark film. Isn’t it good for our collective moviegoing soul to wade through such films now and then?”

I’m basically saying I feel badly about having slammed it, given that I admire Kaufman and feel roused by Synecdoche‘s ambition. But I need to disagree with a claim made in Dargis’s final graph, to wit:

“Despite its slippery way with time and space and narrative and Mr. Kaufman’s controlled grasp of the medium, Synecdoche, New York is as much a cry from the heart as it is an assertion of creative consciousness. It’s extravagantly conceptual but also tethered to the here and now, which is why, for all its flights of fancy, worlds within worlds and agonies upon agonies, it comes down hard for living in the world with real, breathing, embracing bodies pressed against other bodies. To be here now, alive in the world as it is rather than as we imagine it to be, seems a terribly simple idea, yet it’s also the only idea worth the fuss, the anxiety of influence and all the messy rest, a lesson hard won for Caden. Life is a dream, but only for sleepers.”

Synecoche, New York did not strike me as “coming down hard for living in the world with real, breathing, embracing bodies pressed against other bodies.” It struck me as coming down hard for the beautiful obstinacy of Charlie Kaufman’s vision, which is basically that life is a flower, a miracle and a banquet all in one, but that we’re all nonetheless fucked and heading for the grave.

Kaufman has said again and again that this movie is about fear of death and decrepitude. In a Salon interview with Andrew O’Hehir up today, he says it thusly:

“I think as you get older you start to — I’ve always been preoccupied with issues of dying and illness. All that stuff is not new for me, but it does become more a part of my life as I get older and watch people I know die and get sick. It’s a real thing and it’s a universal thing. No matter where you are in your life, it dictates your decisions.

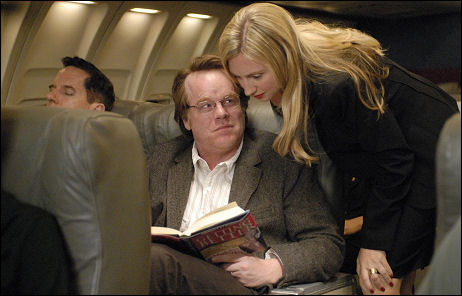

Hoffman, Hope Davis

“I know that as a very young child, I was afraid of death. Many children become aware of the notion of death early and it can be a very troubling thing. We’re all in this continuum: I’m this age now, and if I live long enough I’ll be that age. I was 20 once, I was 10, I was 4. People who are 20 now will be 50 one day. They don’t know that! They know it in the abstract, but they don’t know it. I’d like them to know it, because I think it gives you compassion.”

All that is well and good, but does this sound like a guy who in the final analysis believes in and swears by the primal simplicity and transcendence of bodies and souls hungrily entwined?