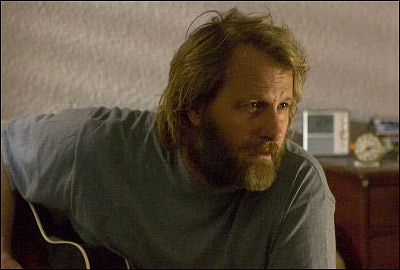

Last Monday afternoon I did a brief phoner with the great Jeff Daniels while standing outside a neighborhood luncheonette on Madison and 81st. The idea was to pay tribute to his fine supporting performance in The Lookout, Scott Frank‘s midwestern bank-job drama. Daniels plays a guy named Lewis — a lazy, bearded, low-rent, shoulder- shrugging, guitar-playing, middle-aged smartass — with a dry, succinct wit that settles in and hits the spot. He’s far and away the best thing in the film.

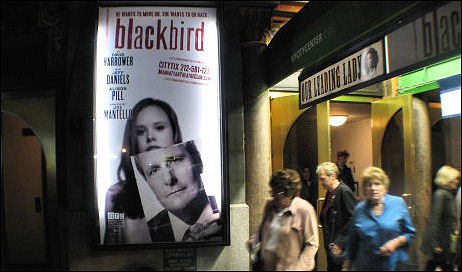

After last Tuesday’s performance of

Blackbird at the Manhattan Theatre Club — Tuesday, 3.27.07, 9:20 pm

I’m not a huge fan of The Lookout (it has a few good things), but I really liked Daniels and I was trying to do Frank a small favor. But I waited until today to run this piece, and that makes me two days late and a dollar short. The Lookout opened and died this weekend with only $1,929,000 in the till and $2000 a print. Face it — DVDs of The Lookout will be sitting in the Walmart bargain bin four or five months from now. It’s a cold, cruel, fuck-you world out there.

Plus the interview, frankly, didn’t go all that well. Daniels was in a cranky, almost bitter mood and preoccupied by the emotional load of playing a very difficult lead role in David Harrower‘s Blackbird, a play that was in previews at the Manhattan Theatre Club. His character, Ray, is a guy in his mid ’50s who’s done time for having had a brief affair with a 12 year-old girl named Una when he was 40. The play is about the girl, now 27 (and played by Allison Pill), visiting Ray and wanting to regurgitate and hash things over in more ways than one.

Playing the role, Daniels said, is harrowing, draining, bruising. I mentioned an actor friend who used to unwind from a difficult role by getting a shiatsu massage after each performance. Not in that realm, said Daniels. Getting into Ray makes him feel like he needs the services of a therapist.

Daniels in

The LookoutIs there some way we could meet before or after the play, I asked, so I could take a quick photo? I can’t see doing that, Daniels said. Talk to the Lookout publicist. What if I stood outside with the autograph hounds after a Blackbird performance and snapped a shot when you come out…how would that be? Still don’t see it, he replied. I might not come out right away, it depends what door I leave by, there might be notes, I don’t like to do that stuff anyway.

Scott had spoken favorably to Daniels about me, which was why we were talking there and then. “I mean, I can’t even believe I’m talking to you,” he said at one point, meaning that he was whipped and disturbed and phoners like this were above and beyond the call. I wasn’t offended, but I can’t say I was charmed.

I tried some standard flattery (like mentioning how much I liked him as Chris Reeve‘s boyfriend in the 1981 B’way production of The Fifth of July), but that didn’t help much. Daniels just said “thank you” a couple of times, and the conversation seemed to stop each time he said that, and I started to feel like a kiss-ass. It was basically a dud conversation all around.

So I called the publicist for Blackbird and asked for a couple of press comps. She obliged, and I saw Daniels do the hard thing last Tuesday night. Blackbird is a 95 minute one-acter, and pretty much a straight sprint. It holds you with a hard grip. And Daniels is damn impressive. Not touching, exactly, since he’s playing a kind of monster, but it’s a steady “wow, wow, wow” thing to watch him go to town. He should end up with some great reviews when the play opens on April 10.

Four people walked out, but that’s to be expected, I guess, with a play about a pedophile and his victim. Except it’s not that cut and dried.

Directed by Joe Mantello, Blackbird is about two people who are totally destroyed by the fact that they were genuinely in love (or something close to that), and who briefly and clumsily acted on it and have been paying for this criminal sin for 15 years and counting. It’s also about dealing with guilt and trying to move on. It could also be about a serial molester who’s never moved on at all.

This is Lolita territory, of course, which means that it’s not just about an older guy having his way with a lamb in the woods (although it was certainly that in part). Ray’s crime was loathsome, of course, but it’s clear from listening to the 27 year-old Una that she had some pretty strong feelings at the time of the seduction that were nearly the equal of Ray’s, and that putting this kind of relationship in a box and keeping it there isn’t easy or simple.