If you want a really accurate, no-holds-barred portrayal of American affairs, go to the Europeans. An 11.1 Der Spiegel article called “A Superpower in Decline” — written by Klaus Brinkbaumer, Marc Hujer, Peter Muller, Gregor Peter Schmitz and Thomas Schulz, and translated from German by Christopher Sultan — is one of the bluntest and most concisely phrased and, to my mind, most persuasive assessments of what’s going on today.

It basically suggests that Jon Stewart was wrong last weekend when he said “we live now in hard times but not end times.” Not the religious nutter kind, of course. It says that the U.S. is suffering a profound economic asphyxiation. It also implies that Tony Soprano wasn’t wrong when he said, “I’m getting the feeling that I came in at the end. The best is over. I think about my father. He never reached the heights like me. But in a lot of ways he had it better. He had his people. They had their standards. They had pride. Today, what do we got?”

The last third of the article is mostly about how the present and future states of the American economy might adversely affect the European and Chinese economies. And the opening is a little wind-baggy. But the middle section seems brutally on-target. I found it massively depressing. Much of what it contains is also articulated in broad strokes by Charles Ferguson‘s Inside Job. The following portion goes on a bit, but read it and tell me we’re not chest-deep in a swamp:

“When Alan Greenspan came to Washington in 1967, as a campaign advisor to Richard Nixon, the old order of the New Deal was still in place. The unions were powerful. Big corporations like General Motors, General Electric and ITT controlled the market. But Greenspan felt that the old order was too sedate.

“He placed great stock in the experiences of his friend, the Russian immigrant and philosopher Ayn Rand, who wrote about the evils of collectivist systems. ‘What she did…was to make me think why capitalism is not only efficient and practical, but also moral,’ Greenspan said. ‘Parasites who persistently avoid either purpose or reason perish as they should.’

“Ronald Reagan was a rising regional politician in California at the time. He believed that the government was not the solution to all problems; rather that government was, in fact, the problem itself. In his biography, Reagan wrote: ‘People are tired of wasteful government programs and welfare chiselers, and they’re angry about the constant spiral of taxes and government regulations, arrogant bureaucrats, and public officials who think all of mankind’s problems can be solved by throwing the taxpayers’ dollars at them.’

“The beginning of the 1980s offered conservatives the opportunity to reshape the country as they saw fit. Unions were suffering from a decline in membership. Technical advances enabled companies to produce smaller quantities cost-effectively and thus gain access to markets previously dominated by major corporations. Reagan took advantage of the weaknesses of the old order to deregulate the economy.

“When air traffic controllers went on strike for higher pay, Reagan fired them and banned them from federal service for life. He also deregulated the telecommunications industry, the shipping industry, banks and commercial aviation, and he lowered the maximum tax rate from 70 to 28 percent.

“The United States became a different country, a radical, free, forward-looking and bold country — a triumphant country, or so it appeared.

“Exporters from other countries surged into the American market, first from Japan and later from China and India. The internet became popular. The deregulation of the financial markets awakened interest in stocks as a financial investment. The retailer Wal-Mart displaced automaker General Motors as the world’s largest company. In this new order, the consumer was among the winners. The investment fund was the modern advocacy group. Banks became more important, and the banking industry had managed to double its profits since the 1970s. Shortly before the crisis, almost 40 percent of American corporate profits were made in the financial sector.

“But was it healthy and sustainable?

“Fast money was too sexy. In those days, before the crisis, 40 percent of Harvard graduates were taking jobs in the financial and business sectors, earning three times as much as their fellow graduates working in other fields. Trading in financial products had become more lucrative than producing goods.

“But because this remnant of the economy still needed to be kept happy, consumers had to keep on consuming, buying bigger cars and bigger houses. Consumer spending made up more than 70 percent of total economic output. But consumers were also spending more than they made, and the savings rate was shrinking. Americans made up for their stagnating or declining earnings by borrowing money. This created a need for lower interest rates.

“Robert Reich has dissected the causes of the crash in his book ‘Aftershock,’ in which he analyzes an American character trait that seems oddly simplistic: If my neighbor has more, than I want more too. And I get what I want, because I’m an American.

“The country, Reich believes, is being threatened by what he calls a ‘perfect storm.’ The wind is blowing from three directions. The rich keep getting richer, with the top 0.1 percent of income earners making more money than the 120 million people at the bottom of the income scale. The rich, says Reich, are trying to buy the elections. Meanwhile, the government is not helping the poor, and in fact is telling them: There’s no money left for you. It is human nature to want what others have, says Reich, but the real problem is that people aren’t making enough money, and that America’s wealth is concentrated within the small upper class.

“All of this is making radicals more vocal. ‘I think what we’re seeing now in America is an outbreak of isolationism, nativism and xenophobia,’ Reich says, pointing toward animosity toward immigrants, accusations against China and growing skepticism of foreign trade.

“When the dotcom boom suddenly ended on the stock markets around the turn of the millennium, prices fell by 78 percent on the NASDAQ. Investors pulled their money out of stocks and invested it in real estate instead. The stock market bubble turned into the real estate bubble.

“‘The US economy has been losing momentum for the last decade,’ says Edmund Phelps, winner of the 2006 Nobel Prize for economics. According to Phelps, it has been increasingly clear, since the beginning of the millennium, that no new jobs are being created on balance, because the US economy has undergone structural change. Companies are dominated by investors interested only in the kinds of quick and large profits that can be achieved by reducing the workforce. Almost 6 million jobs have been eliminated since 2000. Today only 9 percent of Americans work in the manufacturing industry — half as many as in 1985.

“‘America has to change,’ says Obama’s economic advisor Paul Volcker in New York. ‘I wish we had fewer financial engineers and more real engineers instead, like mechanical engineers.’ America, according to Volcker, must ‘rebuild its industrial sector.’ Since World War II, job growth has kept up with population growth, ranging from 10 to 20 percent per decade. The country was firmly convinced that it could continue to do so. In the last decade, the population grew by 25 million, but there were no new jobs, or at least no net job creation. But a minimum of 100,000 new jobs a month was needed just to serve those who wanted to enter the job market.

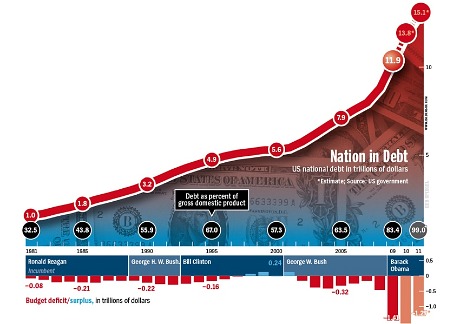

“When Greenspan cleared out his Washington office on Jan. 31, 2006, he left behind a country deeply in debt. Two wars, one in Iraq and one in Afghanistan, had already cost the country $1 trillion. The government debt continued to grow, from 57 percent of GNP in 2000 to 83 percent when Obama took office in 2009. The current national debt of $13.8 trillion amounts to 94.3 percent of GNP, and in two years it will exceed 100 percent. But what’s the next threshold if the pain threshold has already been breached?

“The unemployment rate in the United States is at about 10 percent. But when the people who have stopped looking for work and are not registered anywhere are included, the real number is likely to be closer to 20 percent. For the first time since the Great Depression, Americans have a problem with long-term unemployment.

“In a country with a limited concept of social cohesion, laughable from a European perspective, the quiet demise could have unforeseen consequences. How strong is the cement holding together a society that manically declares any social thinking to be socialist? The US economy lost almost 100,000 jobs in September. Is this Obama’s fault?

“Dinesh D’Souza, a former advisor in the White House of President Ronald Reagan who is now the president of The King’s College in New York, has written a 258-page bestseller about Obama, ‘The Roots of Obama’s Rage.’ The title itself ought to be a joke.

“It has been a long time since the United States has had such a levelheaded president as Obama, a man who governs so dialectically and didactically, who spends so much time listening, weighing options and calmly arriving at his decisions. The president has a lot of problems, including many inherited from his predecessor. He also has a hard time coming across as warm and empathetic. He is good at generating enthusiasm in crowds but, unlike Clinton, he is not adept at connecting to people on a more personal level. Obama feels uncomfortable when he faces someone like Velma Hart. But angry? Obama?

“The Tea Party, that group of white, older voters who claim that they want their country back, is angry. Fox News host Glenn Beck, a recovering alcoholic who likens Obama to Adolf Hitler, is angry. Beck doesn’t quite know what he wants to be — maybe a politician, maybe president, maybe a preacher — and he doesn’t know what he wants to do, either, or least he hasn’t come up with any specific ideas or plans. But he is full of hatred. And so is Dinesh D’Souza.

“Indeed, the United States of 2010 is a hate-filled country.

“D’Souza says that Obama’s father was an anti-colonialist and that he dreamed of his native Kenya liberating itself from its British colonial rulers. His son Barack has the same dream, says D’Souza. He wants to put America, the neo-colonial power of the 21st century, in its place. ‘The most powerful country in the world is being governed according to the dreams of a Luo tribesman of the 1950s,’ D’Souza writes. ‘America today is governed by a ghost.’

“D’Souza’s book has been a huge success, reaching fourth place on the New York Times bestseller list. The Washington Post published an opinion piece by the author, Forbes had him write a cover story, and D’Souza himself thinks he knows why so many people believe that Obama was not born in the United States and is a Muslim. People can’t identify with him, says D’Souza, because he doesn’t believe in the American dream.

“This is the climate in the country leading up to the Congressional elections on Nov. 2. It isn’t shaped by logic or an interest in rational debate. The United States of 2010 is a country that has become paralyzed and inhibited by allowing itself to be distracted by things that are, in reality, not a threat: homosexuality, Mexicans, Democratic Majority Leader Nancy Pelosi, health care reform and Obama. Large segments of the country are not even talking about the issues that are serious and complex, like debt, unemployment and serious educational deficits. Is it because this is all too threatening?

“It has become a country of plain solutions. People with college degrees are suspect and intelligence has become a blemish. Manfred Henningsen, a German political scientist who teaches in Honolulu, Hawaii, calls it ‘political and economic paralysis.’ One reason for the crisis, says Henningsen, is that the American dream, both individual and national, has in fact always been a fiction. ‘This society was never stable. It was always socially underdeveloped, and anyone who talks about the good old days today is forgetting the injustices of racist America.”

“Agitators like Glenn Beck are ‘nationalist, racist and proto-fascist,’ says Henningsen. ‘They take advantage of the economic situation, almost the way the right-wing intelligentsia did back in the Weimar Republic.’

“Gridlock has become the modern America status quo, and the condition Henningsen calls ‘institutional idiocy‘ is especially obvious in the country’s most important legislative body, the Senate, which has come to resemble a royal court where nothing has happened in centuries.

“Each state elects two senators, including Wyoming, with its 540,000 inhabitants, and California, with a population of 37 million. If enough senators from states with small populations band together, they have the capacity to block everything, which is precisely what they do. And no one questions the rules, both written and unwritten. The Senate is no longer a club in which the members speak to one another. The filibuster, a way of blocking legislation through continuous debate, was the exception in the past, but today it’s the rule. The Republicans have already used the filibuster to torpedo more than 100 of Obama’s proposals.”