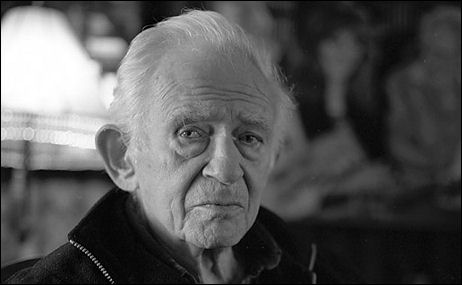

Norman Mailer‘s passing this morning feels to me like the loss of a beloved uncle. He wasn’t much of a filmmaker, but he was a genius, a great writer and a literary superstar for the ages. And a very decent and considerate fellow to interview and share thoughts with.

Mailer had the reputation in his middle-aged years of being susceptible to hubris and brutality, but he became a much better human being when he got older. (As many of us fortunately do.) I developed a sense in the late 1980s and ’90s, in fact, that he’d matured into one of the gentlest and wisest men in American literary life. I’ve always felt closer to him emotionally than I ever have to my father, and so this morning’s news left me with a feeling that I’d lost someone I truly knew and had cared for.

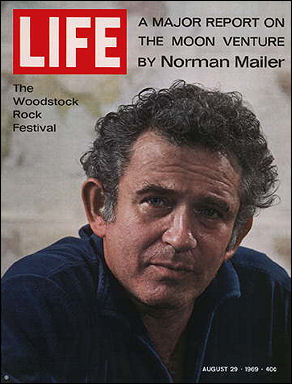

Listen to this passage from the American Experience documentary about Mailer that aired in 2000. It tells you a little bit about who he was in terms of the literary influences upon his generation. He was a wonderfully articulate man in conversation.

I began admiring Mailer’s writing when I was 17 or 18, in part because I sensed genius in him, but largely because his lion-like, sometimes reckless tough guy manner struck a chord. His observations seemed to drill right into the molten core in a way that sometimes brought an almost religious clarity to things. So it naturally meant a lot when I worked with him on the press kit for Tough Guys Don’t Dance, which he directed for Cannon Films (where I worked for two years in the mid ’80s) and which opened in September 1987.

He was in a pissy mood when I called him to do the initial interview. But we eventually got rolling and he gradually came to realize I wasn’t an idiot. By the end of our 45 minute chat he said he was sorry for having an attitude earlier. I later faxed him a rough draft of the piece I wrote from our discussion, and I remember what a thrill it was for the great Norman Mailer to be telling me what words to eliminate and what substitutions to use and where to put the commas and so forth. We met and spoke a few weeks later, but that editing session was the greatest.

A year or two later I went to see him speak at UCLA. Peter Rainer was also there. I remember Mailer reading a portion from Ancient Evenings.

I’ve read most of Mailer’s books and essays, and yet, oddly, never The Naked and the Dead or The Deer Park. I’ve especially loved Armies of the Night, The Executioner’s Song, Miami and the Siege of Chicago and The Prisoner of Sex.

I sympathized with his dislike of the word “relationship,” which he regarded as arid, clinical and officious. I still love his idea about a child’s strength of spirit being a result of how impassioned the sex was between the parents at the moment of conception. And I love that sentence Mailer wrote in his review of Last Tango in Paris about Marlon Brando having “cashed the check that Stanley Kowalski wrote 25 years ago” with that stand-up overcoat sex scene between himself and Maria Schneider.

And Tough Guys Don’t Dance was an interesting film. Avant garde in a sense. Telluride Film Festival chief Tom Luddy called it “Tarantino before its time…long, florid dialogue punctuated by grotesque violence followed by more long, florid dialogue and then more grotesque violence.” (The quote is from a Mark Singer New Yorker piece about a Tough Guys Don’t Dance reunion that happened last year.)

Mailer lived a rich life, 84 years worth, and there’s no inherent tragedy when a journey comes to an end. But his death is one of those events that makes the passage of time feel a bit more ominous and unnverving.

Mailer’s candor was unusually giving and generous. “Writers aren’t taken seriously anymore,” he once said, “and a large part of the blame must go to the writers of my generation, most certainly including myself. We haven’t written the books that should have been written. We’ve spent too much time exploring ourselves.”

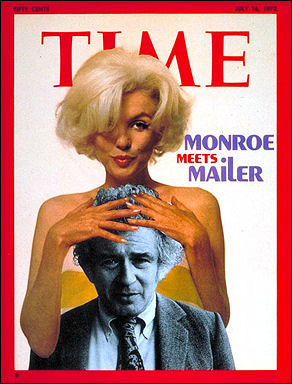

Read The Gospel According to The Son, particularly the last chapter, and tell me this isn’t a guy who understands the all of it. It’s a modest work, yes, but very delicate and beautiful. I haven’t even read his Hitler book, but I intend to. Some of the things he said about Marilyn Monroe (in that coffee-table essay he wrote about her in the ’70s) have stayed with me for decades.