Not long after Elvis Presley died of a drug overdose in August 1977, the blunt- spoken John Lennon told a reporter that Presley “died in 1958, when he went into the Army.” An honest response to the death of the print version of Premiere magazine, which was revealed today, would be along the same lines: Premiere — the once-ballsy Hollywood magazine that was about nervy, sharp reporting and not upscale fan-mag aesthetics — died in May 1996 when much of the upper-level staff quit over editorial interference.

“You could feel the life forces leaving at that point,” recalls L.A. Times staffer Corie Brown, a former Premiere columnist (“California Suite”) and West Coast editor.

Brown was quick to praise Susan Lyne, now CEO of Martha Stewart Omni, for having launched Premiere in 1987 and running it for eight years, until 1995. “She was the guiding force,” says Brown. “And Chris Connelly was her deputy until she left, and then he took over. They were the two best editors I ever worked for.”

Premiere maintained high writing and editing standards after May ’96, but things were never quite the same. It gradually became a smart, respectably configured fan magazine — above-average writing and reporting (by L.A. Times staffers John Horn and Patrick Goldstein, Christine Spines, Fred Schruers, et. al.) and good film criticism by Glenn Kenny — and yet, in the view of most, a shadow of its former self.

Print publications are getting killed left and right by the internet these days, and that’s what got Premiere in the end. Ad Age‘s Nat ives wrote earlier today that Premiere‘s “paid circulation has declined slowly over the years, from an average of 616,089 in 1995 to 492,498 in the second half of last year, according to Harrington Associates and the Audit Bureau of Circulations.

“Even more ominous,” wrote Ives, “Premiere sold 24.7% fewer ad pages in 2006 than it did the year before, according to the Publishers Information Bureau. Titles and websites focused on celebrity gossip, meanwhile, have continued to gain circulation, making it difficult for older entertainment brands.”

“I do believe that the world has turned to get information online,” said newly- installed Variety columnist Anne Thompson, who was Premiere‘s West Coast editor from July 1996 to June 2002. “And running a monthly film magazine…a costly monthly operation at a time when everything is getting faster and faster….that’s a tough order.”

The online version of Premiere will continue. The print version’s editor, Peter Herbst, is out the door. The April issue will be the final one. A friend of a friend had been working on Premiere‘s “power” issue due in June…forget it. A source in Premiere‘s New York office said “the mood here is pretty frustrated, but this wasn’t completely unexpected.”

Premiere‘s 1996 editorial revolt happened when Hachette Filipacchi CEO David Pecker accepted “the resignation of two top editors, Chris Connelly and Nancy Griffin, and a near rebellion by the staff” (according to a Time magazine report) over the spiking of a “California Suite” column by Corie Brown about “business deals involving Sylvester Stallone and the Planet Hollywood restaurant chain”, which had venture plans at the time with Premiere‘s owner Ron Perelman.

One of the stars of the glory-days Premiere was Slate columnist Kim Masters. The top players in Masters’ era (she worked there from ’87 to ’90, give or take) were Lyne, Connelly, Peter Biskind, Griffin, Brown and John Richardson. (A star-in- the-making was E! columnist Bruce Bibby, who worked as a fact checker during Masters’ time.).

“My first piece was about Ovitz making a big scene at the Palm when some agents had defected from CAA, and Ovitz made a big flap about it, he didn’t want them eating there,” Masters says, “and I remember an editor read it to [then-publisher] Rupert Murdoch, and he laughed at the piece and said it was fantastic.

“That was the golden age of Premiere,” she recalls. “That was when the Power list was created. That was when we coined the term ‘Young Turks’, which I had gotten from doing legal reporting and hearing that term used in law firms. Things were so different in those days….a very different internet-free world.

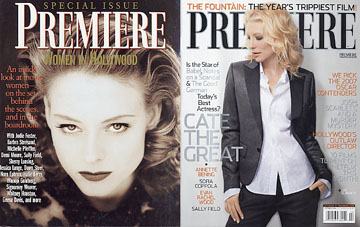

founder and former Premiere editor Susan Lyne

“I did a big investigation of a Delta Force helicopter crash, in which several people were killed,” she recalls. “An interview piece about Sam Kinison. A great Roger Rabbit piece….I remember sniffing around about the film early on and getting this call from Jeffrey Katzenberg, saying what are you doing to my movie? Premiere was ballsy enough back then to fly me to London [where Roger Rabbit was shooting] when we had no access…they just sent me there and waited for the studio to cave.

“I remember when John Richardson and I were working on a power list [in ’92 or thereabouts], and we were sitting with Mark Canton in his office at Sony and he was saying, “I make the decisions! I run the show!…and Peter Guber stuck his head in and said, ‘I need you now‘ and Canton got right up and followed him out. And of course, Nancy [Griffin] and I Nancy and I wrote the story that was the origin of Hit and Run,” the 1997 best-seller about how Guber and Jon Peters “took Sony for a ride in Hollywood.”

“It was a good magazine, but that was such a long time ago,” says Masters. “It just went off the radar.”