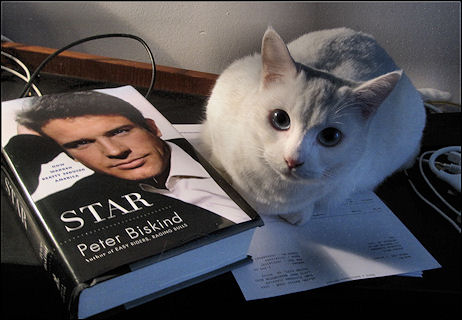

I’ve finally received a copy of Peter Biskind‘s Star: How Warren Beatty Seduced America (Simon & Schuster, 1.12.10), and have spent a total of 20 minutes of dancing through it and dwelling here and there. It’s a pleasure to read just for the quality of the writing and editing. Well-shaped sentences that are no longer than they need to be, and paragraphs that hatch and develop a thought or a mood or a theme, sometimes all three at the same time.

And I can tell right away that it’s been written as a kind of tragedy, or rather that Beatty’s career (as opposed to his life) has ended up that way, certainly over the last ten years, and that Biskind, being a diligent reporter and a sage fellow, has gone down that path because that’s where this beastly endeavor has taken him. Biskind has been on it since at least ’04.

“Finishing this book was like recovering from a lingering illness, although admittedly one that I had brought in myself,” Biskind writes at the start of “Warrenology: An Introduction,” about ten pages before the narrative begins.

Is “tragedy” too harsh or dismissive a term to use about Beatty’s gradual withdrawal from the hey-hey since Town and Country? Would it be fairer or kinder to say his lack of productivity (i.e., acting career over, not having directed a film) and his failure to become another Clint Eastwood has been simply due to his having gradually scared more and more would-be collaborators away because he’s so cautious and guarded and slow-moving and fickle? Would it be wrong to say that the regrettable lesson of Beatty’s late career has been (take your pick) if you cruise you lose, time is shorter than you think, shake it when you can, and keep dancing until you’re dead?

In the final chapter, on page 547, Biskind writes the following: “It is shocking to imagine a star as bright as Beatty was, as famous and powerful, and as gifted, being virtually unemployable.

“There’s no shortage of reasons that explain why filmmakers go into decline. In America, at least, the movie business has always been a young man’s game. Directing is hard, as physically and mentally demanding as any job on the planet. Filmmakers grow old and get tired like everyone else, while their audience seems to remain perennially young. Once directors become successful, they too often enter a bubble of privelege and lose whatever instincts enabled them to touch their audiences in the first place. As Billy Friedkin once put it, ‘When you take your first tennis lesson, your career is over.’

“‘It’s very hard to keep productive,’ Toback continues. ‘It’s very hard to keep the level up for the game, for the big fight, for the World Series, for the Super Bowl, and still have a life. It’s that game that people always want to talk about when they talk about talent. And when you put it out there in the world of insults and acrimony and envy and lividity, it has trouble surviving.’

“Perhaps it’s not Beatty’s last decade that makes people wonder,” Biskind writes, “but the years he spent, so unproductively, chasing skirt. Perhaps it’s the fact that Beatty turned down so many roles, in so many films and missed so many opportunities…he seemed to do so much less than someone with his gifts could have done. Perhaps it’s that he always seemed so emotionally closed, so self-protective that, as Mab Goldman put it, he was unable to ‘stand naked in the storm of life.'”