Yesterday I caught four films over an 11-hour period, and I’ve got another three-and-a-half on the schedule today — a half-hour’s worth of Stevan Riley‘s Listen to Me, Marlon (2:30 pm, Prospector), Anna Boden and Ryan Fleck‘s Mississippi Grind (3:30 pm, Eccles), Noah Baumbach and Greta Gerwig‘s Mistress America (6:30 pm, Eccles) and then, possibly, most of Craig Zobel‘s Z For Zachariah (8:30 pm, Library). And if I want to be a serious madman I’ll catch an 11:30 pm screening of Patrick Brice‘s The Overnight at the Prospector.

On top of which I’m moving this morning from the somewhat larger suite #121 at the Park Regency to the somewhat smaller #124, which should take about an hour. A tight clock. Oh, to wander through the Sundance Film Festival solely on whims and instinct with no need to file…stop dreaming.

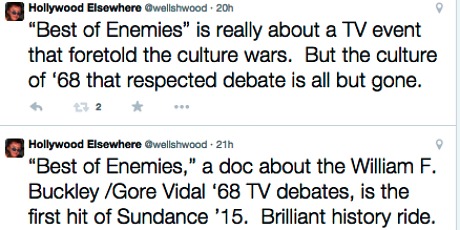

For me the smartest, most engaging and fully realized film I saw yesterday was Morgan Neville and Robert Gordon‘s Best of Enemies, a wise and propulsive capturing of a kind of clash-of-the-titans TV debates between William F. Buckley and Gore Vidal during the 1968 Democratic and Republican conventions.

But running a close second was Andrew Mogel and Jarrad Paul‘s The D Train, by far the darkest and nerviest laugher I’ve seen in ages. It begins as a not-too-funny situation comedy about a neurotic, high-strung suburban family man (Jack Black) who goes to great fraudulent lengths to travel to Los Angeles to lure a former high-school classmate who’s now a more-or-less-failed Hollywood actor (James Marsden) to a 20th anniversary high-school reunion.

What I didn’t expect to see was a detour into Brokeback Mountain territory by way of a Lars von Trier film. But at the same time, as I mentioned during the post-screening q & a, The D Train follows the classic structure known as “the Three Ds” — desire, deception and discovery.

I can’t call The D Train howlingly funny — nobody could — but it’s brave and different and much darker than what most of us would expect when we sit down with a comedy. You can call it “comedic” and that’s fine, but it’s really a kind of laugh-sprinkled Middle American psychodrama about denial, suppression, self-loathing and the traumatic process of change. And yet it ends on a note of comfort and completion.

And Marsden manages his most charismatic, naturalistic and altogether winning performance, recalling on one level the ghost of Warren Beatty‘s tragic George Roundy in Shampoo and on another level personifying a form of failure and self-loathing and yet mitigated by self-acceptance, and resignation, which is to say style and grace…a wilting of the spirit.

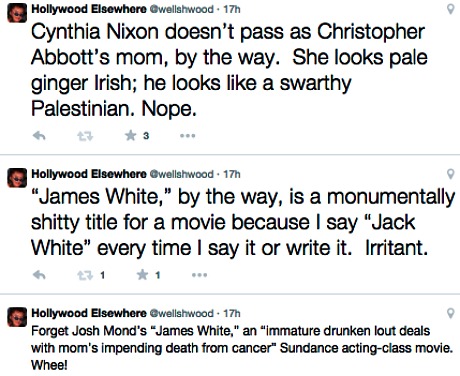

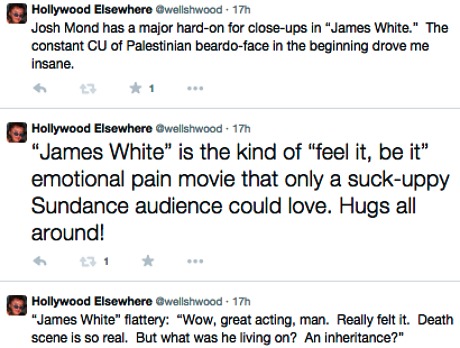

I respected Josh Mond‘s James White as far as it went, but I more or less hated it for many of the reasons that Indiewire‘s Eric Kohn, who tends to be friendly to many experimental indie filmmakers, praised it to the heavens. It’s well acted (particularly by Christopher Abbott) and nicely handled in some respects, but it’s mainly a sketchily written acting-exercise flick with way too many close-ups and not enough story. Without Cynthia Nixon’s dying-of-cancer scenes if would be almost nothing.

I knew I was in for a difficult sit when Mond introduced the film in a kind of muttering half-speak. He somehow couldn’t manage to enunciate or speak loudly enough to be heard with any real clarity. “This guy’s full of himself,” I said to myself right away. “He thinks he’s Mr. Sensitive King Shit Artiste, and he’s obviously a hider.” If a director can’t stand up and man up in front of a crowd and explain himself, what good is he? Mond has a Brooklyn beardo twee vibe that just rubbed me the wrong way. That and his muttering and the relentless close-ups of Abbott that begin the film are a problem. His casting judgment is also in question as far as Nixon is concerned. She nails her part as Abbott’s dying mom, but a woman this fair-skinned, ginger-haired and Irish-looking could never be the biological mother of the swarthy, dark-haired Abbott, who has a kind of Egyptian or Palestinian or lower Mediterranean vibe.

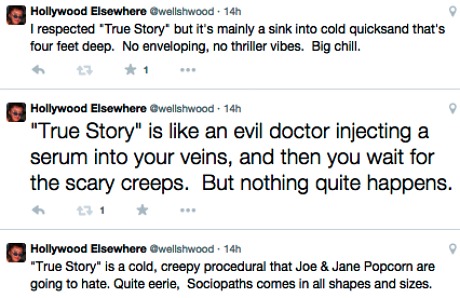

I haven’t time to get into Rupert Goold‘s True Story (later today?) except to say it’s very well made — clean, assured, well-ordered — to relatively little effect.

It’s basically a chilly procedural, based on Michael Finkel‘s real-life account (“True Story: Murder, Memoir, Mea Culpa“), about a couple of guys who couldn’t be more different, a journalist (Jonah Hill) and a murderer (James Franco), who nonetheless share a sociopathic nature. They’ve both done things that are self-destructive and inexplicable, Finkel (Hill) having gotten fired from the N.Y. Times for inaccurate or falsified reporting and Christian Longo (Franco) having murdered his family and then used Finkel’s name while on the lam in Mexico. This, at least, is how it seemed to me. The film explains all this and deals with the lying (mostly on Franco’s part) and then a murder trial reveals the facts and then things more or less wind down.

True Story isn’t so much chilly as coldly efficient — a well-honed, mildly creepy thing. But I’m not understanding why anyone thought there was a compelling film in Finkel’s book.