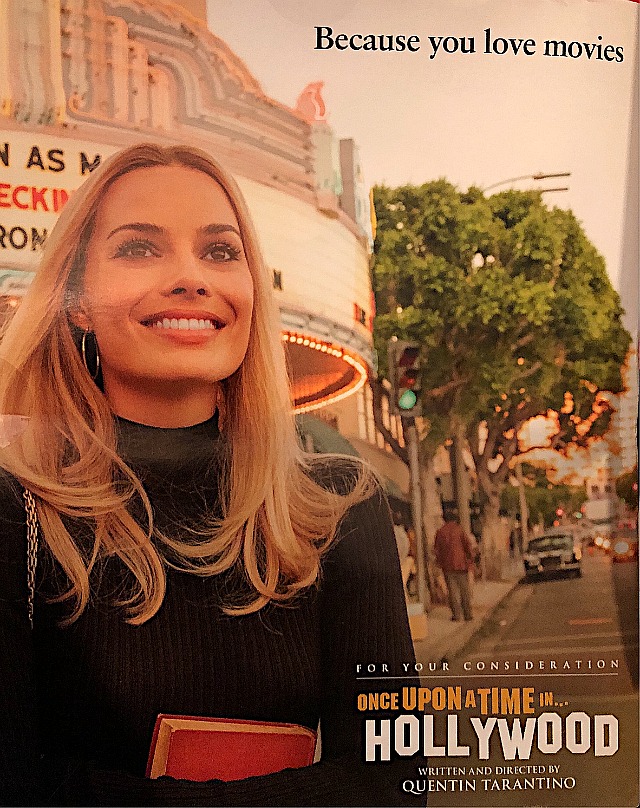

“Because you love movies,” the latest Once Upon A Time in Hollywood ad says. This is a positive coded message. It means that serious fans of Quentin Tarantino‘s ninth film are relaxed and sophisticated enough to see past aspirational, vaguely academic notions about “cinema” and the learned attitudes they connote — they’re down with confident, engaging, cool-as-shit flicks.

In part because they know (and this is a sophisticated idea that’s been brewing since the Cahiers du Cinema days of future director Jean-Luc Godard) that some of the greatest and most satisfying big-screen experiences, not to mention those that have delivered great and lasting art, were made with the initial idea of being audience-friendly entertainments.

In short, a film doesn’t have to be artistically “serious” or pretentious to be worthy of critical admiration, and perhaps even win a Best Picture Oscar.

As I mentioned earlier this month, Once Upon A Time in Hollywood winning the big prize would be a unique historical achievement. It would be the first time in Hollywood history that an amiable, relatively plot-free, character-driven, laid-back attitude flick wins the big prize.

To put it more simply and given the fact that Tarantino’s film is a celebration of the B-movie realm of 1969 Hollywood, it would be the first “drive-in movie” to win this honor. A more on-point description would be “hangout movie“. In the vein, say, of Tarantino’s Jackie Brown (’98), which, until OUATIH came along, is arguably his finest and most engaging film of the last 20 years.

Perhaps the most precise analogy of all is Howard Hawks‘ Rio Bravo (’59), which Tarantino has described as “the ultimate hangout movie” and which he’s been enthusing about for decades.

You could actually call Once Upon A Time in Hollywood a kind of Rio Bravo tribute. The parallels aren’t abundant, but they’re evident.

Rio Bravo‘s two main characters are John Wayne‘s “John T. Chance”, a gruff, mince-no-words Texas sheriff, and Dean Martin‘s “Dude”, the town drunk who used to be good with a gun. In Tarantino’s film Brad Pitt‘s Cliff Booth is a vaguely Wayne-like stunt man, driver and gopher — laid-back, steady, confident — and Leonardo DiCaprio‘s Rick Dalton is certainly a “Dude”-like actor — formerly a big TV western star with a top-rated series (Bounty Law), now beset with career worries and an alcohol problem.

The Rio Bravo villains are the ranching Burdette brothers (Nathan and Joe) and their gang; the baddies in Tarantino’s film, of course, are the Manson family and particularly Tex Watson, Susan Atkins (aka “Sadie”), Linda Kasabian (“Flower Child”) and Patricia Krenwinkel (“Katie”).

Rio Bravo concludes with the drilling of the Burdettte gang by John T. and Dude (aided by Walter Brennan‘s “Stumpy” and Ricky Nelson‘s “Colorado”), while OUATIH ends with the walloping, face-mashing, pitbull-chewing and flame-throwing incineration of the Manson ogres by Cliff and Rick.

And both films are mainly about…well, talking shit and sizing up the situation and to some extent dealing with kindly Mexican fellows (Pedro Gonzalez-Gonzalez‘s “Carlos” in Rio Bravo + the car attendants at Musso & Frank whom Cliff tells Rick not to cry in front of) and wondering what’ll happen down the road. Basically marking time with sweat and anxiety mixed with occasional fraternal chillin’ and the mopping of brows. Plus Dude and Rick fretting over their respective alcohol issues.

Both films allow their audiences plenty of time to get to know their imperfect protagonists, and to savor the idea of loyalty and friendship put to the test and holding fast.

Arguably the coolest thing about Once Upon A Time in Hollywood is that it doesn’t feel overly anxious or clenched or drill-bitty about delivering the goods. It takes its own sweet time getting, and in so doing invites the audience to settle into the realm of 1969 Hollywood. Partly “this was Hollywood of the old days” nostalgia, and partly taking the temperature of a turbulent time.

Godard once wrote that the exceptionally good things in Rio Bravo can be ignored, and therefore may be unnoticable to a good-sized portion of the audience.

“The great filmmakers always tie themselves down by complying with the rules of the game,” Godard once said. “Take, for example, the films of Howard Hawks, and in particular Rio Bravo. That is a work of extraordinary psychological insight and aesthetic perception, but Hawks has made his film so that the insight can pass unnoticed without disturbing the audience that has come to see a Western like all others. Hawks is the greater because he has succeeded in fitting all he holds most dear into a well-worn subject.”

Tarantino arguably does the same thing in Once Upon A Time in Hollywood. He’s conveying perceptions about friendship, hubris, failed careers, alcoholism and a certain demonic undercurrent in the ’69 counter-culture, but he’s doing it with an entertaining approach and a frequent wink of an eye.

If Hawks could somehow return to Hollywood and make the social rounds, he would enjoy Tarantino’s company as well as (I’m fairly certain of this) his latest film.