I’ve read more than one description of The Expendables as a kind of ’80s action film. Director-cowriter-star Sylvester Stallone has not only paid tribute to his action-star heyday, but resuscitated the look and style of Reagan-era action flicks (including, to some extent, the calibre of special effects as they existed back then). But there’s a better, simpler shorthand: The Expendables is a 1986 or ’87 Cannon Film. It feels cut from the same cloth as Cobra and Over The Top.

The trick or attitude with The Expendables (or at least one that I suspect was in Stallone’s head when he made it) is that it’s an ’80s action flick in quotes. The fighting and gun battles are staged with vigor and meant to be taken as semi-serious high-throttle diversion, but also with a self-referential nudge. Stallone and Willis and Lundgren and the rest doing the old half-chuckle and saying “remember this shit when it was fresh, or at least fresher?”

Cannon-produced action pics never winked. For all their relentless mediocrity, they all had a fairly solemn tone. But The Expendables summons the Cannon spirit by being fairly cheeseball. It seems to have been made with an assumption that its audience doesn’t want anything too shaded or subtle or deeply felt — that they would actually be unhappy if it went in those directions.

With the exception of Runaway Train, Cannon action flicks were always boilerplate and frequently awful. Anyone who’s ever seen Down Twisted (’87), directed by Albert Pyun, knows what I’m saying.

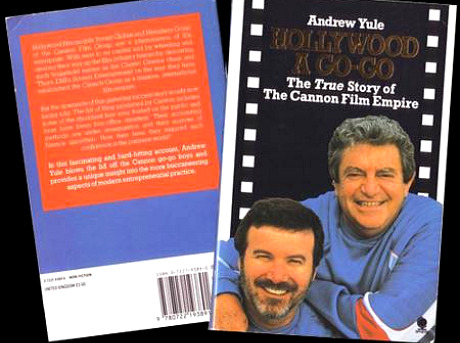

Cannon Films was a very curious culture with an exploitation film attitude (i.e., movies regarded as “product”), but Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus threw a lot of money around and a lot of serious people took it for this and that reason.

“I had my nose pressed against the glass for 20 years,” Norman Mailer once said about Tough Guys Don’t Dance. “It took Cannon Pictures to say they believed in me to the tune of $5 million. There were nights when Menahem Golan woke up and said, ‘I’m giving $5 million to a crazy man who’s never directed a movie? I must be crazy myself.'”

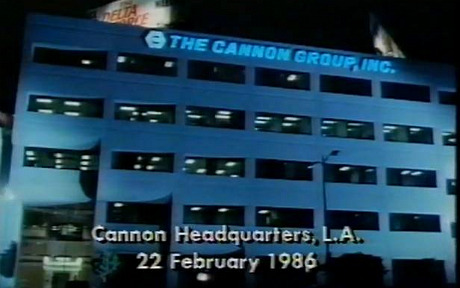

I worked as a Cannon press-kit writer (staff) for much of ’86, all of ’87 and into early ’88, so I know whereof I speak. I know all about that operation and the mentality behind it. There were quality exceptions here and there (which I was very grateful for), but the films were mainly schlock. Which fostered a certain atmosphere among Cannon employees. “Fatalism mixed with humiliation resulting in gallows humor” is one way to describe it.

I had a nice little office on the fourth floor. I had a desk, phone, window, chair, two filing cabinets and a styrofoam ceiling that I used to lob sharp pencils into when I was bored. But I also got to meet and work with Barbet Schroeder on Barfly, Mailer on Tough Guys Don’t Dance, Herbert Ross on Dancers, Tobe Hooper and L.M. Kit Carson on The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, Godfrey Reggio on Powaqqatsi and Richard Franklin on Link.

I barely spoke to Golan and Globus, and that was okay.

But I was in the building when Schroeder stood in Golan’s office and threatened to cut off his finger with an electric chainsaw if Golan didn’t greenlight Barfly. And I talked to Mickey Rourke over the phone once and managed to piss him off (but that was par for the course back then). And I became slightly chummy with former SNL alumnus Charles Rocket (who killed himself about five years ago). And at Schroeder’s insistence I rewrote the Barfly press kit about ten or twelve times (to the point I couldn’t read the sentences any longer), but I learned that relentless re-writing, if you’re tough enough to handle it, does result in a bulletproof final draft.

I also had to write press kits for Allan Quatermain and the Lost City of Gold, Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo, Assassination, The Barbarians, Tobe Hooper’s Invaders from Mars, Masters of the Universe, Down Twisted, The Arrogant and others I’d rather not think about.

Here’s a great Cannon website with several funny quotes.