Thunder Approaching

My baby blues have beheld the majesty of Ridley Scott’s Kingdom of Heaven (20th Century Fox, 5.6).

It may be a little bit early to say what it is, but I think it’s fair to say what it isn’t. That sounds, I realize, like I’m qualifying or being “careful” by saying as little as possible. Not so. I just need to set the record straight about something I wrote about this super-sized epic late last year.

In some ways surprising, in several ways stirring and in almost every way admirable, Kingdom is a big-canvas historical drama that dares to be different. I’m not saying it doesn’t give in to formula now and then, but it’s a complex and unusual thing for the most part, and altogether a textural masterpiece.

That sounds like I’m dodging the central issue of whether it’s entertaining or not. It is, but what got me is the beauty of the brushstrokes. That and the avoidance of the usual usual.

< ?php include ('/home/hollyw9/public_html/wired'); ?>

Has there ever been a big expensive film about warring armies in which one side didn’t triumph absolutely? In which the loser wasn’t totally beaten down and slaughtered? I felt amazed and lifted up when this didn’t manifest…when life and sanity, in effect, is chosen over death and fanaticism.

The 12th Century milieu feels entirely authentic, the big siege-of-Jerusalem battle scene totally aces Peter Jackson’s similar third-act sequence in Return of the King, there are fine supporting performances throughout (especially from Jeremy Irons and a masked Edward Norton), and William Monahan’s script, praise Allah, avoids a lot of black-and-white, good-and-evil stereotypes.

In the title role of Balian of Ibelin, defender of Jersualem, Orlando Bloom has zotzed the girlyman image he created for himself in Troy . He is bearded, grimy, quiet and steady throughout Kingdom of Heaven. He is manly, in short, and does that classic Jimmy Cagney thing — planting his feet, looking the other guy in the eye and telling the truth.

Does he channel Laurence Olivier? No, but Bloom has definitely held his ground here, and the stage is now set for him to carry the ball into the end zone, maybe, in Cameron Crowe’s Elizabethtown.

Ghassan Massoud, the Middle Eastern actor who plays Saladin, makes an especially strong impression. He doesn’t just play a man of honor and a commanding leader — he seems to possess these traits himself, and has made them readable on the screen by just being. It’s one of those “wow, who was that?” performances that should be remembered at year’s end.

But let’s get back to my original point — what the film isn’t. Especially since the unspooling of Kingdom of Heaven argues with a forecast piece that I wrote about and posted on 12.29.04.

This is a film about the Crusades and a decisive late 12th century battle between Muslim and European armies over the occupation of Jerusalem. Given the invading Anglos vs. Middle East natives angle, one might expect Kingdom of Heaven to conjure a political echo or two about the U.S. occupation in Iraq.

At the very least, this seemed like a perfectly logical and reasonable thing to presume.

“9/11 was three years and three months ago, the invasion of Iraq happened in March ’03, and principal photography on Kingdom of Heaven began in Morocco last January,” I wrote. “And in the minds of Scott and his creative team, the U.S. vs. Iraqi insurgent situation didn’t weave its way into the film on this or that level?”

These echoes are there, I suppose, if you want to dig them up. I suppose you could regard the last ten or fifteen minutes of this film in a metaphorical light and say it addresses the fundamental folly of being an occupier, and in fact offers an honorable solution for those who find themselves in this situation.

But Kingdom of Heaven is such an atmospheric reconstruction of the 12th Century, such a devoted here’s-how-it-looked-and-smelled experience, and Scott’s eye is so painterly and his focus so unlike, say, what Oliver Stone’s might have been, that you just don’t get much of a Baghdad/Fallujah/Abu Ghraib residue.

In my 12.29 piece I said, “Can anyone think of another occupying Anglo force that went into a Middle Eastern country for bogus reasons and is probably fated to leave with its tail between its legs?

I then linked to an 8.12.05 New York Times piece by Sharon Waxman that explored this and related issues to some degree.

“With bloody images of Muslims and Westerners battling in Iraq and elsewhere on the nightfly news, it may seem like odd timing to unveil a big-budget Hollywood epic about the ferocious fighting between Christians and Muslims over Jerusalem in the Crusade of the 12th Century,” her story began.

“While the studio has tried to emphasize the romance and thrilling action, some religious scholars and interfaith activists…have questioned the wisdom of a big Hollywood movie about an ancient religious conflict when many people believe that those conflicts have been reignited in a modern context.”

I never got hold of Monahan’s script and I don’t know if Scott cut stuff out in order to de-politicize Kingdom of Heaven, but once it starts to be shown, those scholars and interfaith activists will, in my opinion, have a hard time selling whatever complaints they may have to journalists.

And I’m including anyone in the pro-Islamic p.r. community. I didn’t see anything in this film that dismissed or put down any Muslim characters, or which failed to respect their point of view.

One of my favorite scenes is when Bloom, freshly arrived in Jerusalem, asks where Jesus Christ was crucified and goes there, to the barren hilly area called Golgotha. Then he sits on a hillside and waits for something to happen. The movie becomes very quiet and still, and for almost a minute (or maybe a bit more), everything flatlines.

It doesn’t amount to a condensation of Bergman’s trilogy about God’s silence or anything, but I could feel pleasure seeping in…pleasure in the fact Scott isn’t afraid of taking this movie into a moment of meditation.

I also enjoyed a scene in which Bloom and his soldierly allies dig for water in a barren area, and then find it and create an irrigation system.

I will always remember this film for the sonic impact of those heavy thundering hoofbeats upon my ribs.

The pleasures of the stellar supporting cast are considerable. Everyone shines…Irons, Liam Neeson, Eva Green (last in The Dreamers), David Thewlis, Jon Finch (I always liked his Thane of Cawdor in Roman Polanski’s Macbeth), Brendan Gleeson, Alexander Siddig, Velibor Topic, etc.

I didn’t exactly “like” Marton Coskas’ performance as Guy de Lusignan, one of the really arrogant bad guys who creates most the trouble, but he fills the boots.

I can’t say I’m totally delighted that Scott is still queer for that herky-jerky, skip-frame way of shooting action scenes that he used in Gladiator, but c’est la guerre.

There’s another Gladiator echo in the form of an attacking horsemen scene about ten or fifteen minutes in. It appears to have been shot in the same forest used for the opening battle scene in Gladiator, with the same blue tint and the same digital snowflakes.

One of the Kingdom of Heaven sites is here .

Peet Problem

It was about two and a half years ago when I began to forgive Amanda Peet for being intensely dislikable. And she is that — make no mistake.

I’m sure she’s fast and hip and cool to hang with, but she plays the same kind of woman in film after film, and this can’t be just because casting directors lack imagination and like to play follow-the-leader.

There is something in Peet’s screen attitude that always seems to bring lying, insincerity and cynical mind games to the table. Just as there are faces that radiate warmth and kindness and all that other sweet stuff, there are faces that do the opposite and make you feel wary about everything. Peet’s basic vibe is that of a born conniver.

Peet could never (or at least, should never) be cast in a film like Kingdom of Heaven. There’s something grotesquely and opportunistically “now” about her that doesn’t, I feel, adapt to any other time or sensibility.

Her eyes are striking, to be sure (People called her one of the 50 most beautiful people in the world in 2000), but also shrewd and predatory. She has a smile right out of Fall of the House of Usher with Vincent Price. It says, “You don’t get me and you never will. I’m going to make sure of that.”

But she was truly exceptional as Ben Affleck’s soulless wife in Changing Lanes, particularly in that restaurant scene when she tells Affleck she married him because she knew he would always be the kind of guy who would kowtow to power and do what’s necessary to keep her in clover. It was such a cool scene I figured, okay, give it up.

And then she was fairly agreeable as Diane Keaton’s daughter in Something’s Got To Give and as Will Ferrell’s go-getter spouse in Woody Allen’s Melinda and Melinda.

But now she’s back as Ashton Kutcher’s romantic interest in Nigel Cole’s A Lot Like Love (Touchstone, 4.22) and I’m getting the creeps again. Those photo booth shots of her and Kutcher in the poster…the way she looks and sounds in the trailer. Everything is telling me to duck and hide.

This isn’t very interesting to write about. Gut likes and dislikes are so arbitrary. There must be tens of thousands (or more) who find Peet attractive or funny or whatever. A distributor who wrote me a couple of days ago swears A Lot Like Love is a sleeper, and for all I know I’m the only one who feels this way about Peet. But I doubt it.

A Lot Like Love is said to be an above-average film. It’s about Kutcher and Peet wanting each other and not doing anything about it for seven years because they don’t feel they’re ready to pull the trigger or take the plunge. In other words, it’s a twentysomething movie that basically says, “Relax…chill…you have all the time in the world.”

Well, don’t we?

Pollack Dissing

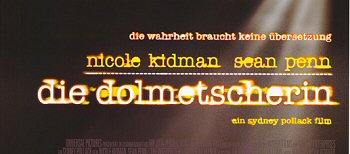

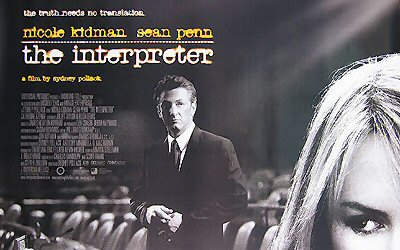

It has been observed that Sydney Pollack’s name is barely legible on the U.S. one-sheet for his latest film, The Interpreter (Universal, 4.22), and that this is probably not an accident.

The words “A Sydney Pollack Film” are printed in a light, barely visible gray and scrunched between the larger, bold-faced names of the film’s stars, Nicole Kidman and Sean Penn. (Pollack’s name is so hazy and small I can’t even find a focused blowup.)

If Out of Africa had won the Best Picture Oscar in ’94 instead of ’84, you can bet Sydney’s name would be a tad larger and probably pop through a bit more. Universal’s marketing guys are definitely making a statement of some kind.

It’s interesting, also, that Pollack’s name is larger and more visible on the English and German one-sheets for the film.

The international ad guys are obviously less concerned about whatever it is that has scared their U.S. counterparts (memories of Pollack’s Random Hearts?). That or Random hearts did better in Europe than it did here.