“Sometimes bein’ a bitch is all a woman has to hold on to.”

Because I was lazy and cowardly I chose to avoid Taylor Hackford, Kathy Bates, Tony Gilroy and Gabriel Beristain’s Dolores Claiborne back in the late winter or early spring of ‘95. It really wasn’t cool that I shut this worthy film out, but I finally watched it last night and holy moley mother of God…it’s exceptionally good!

Shot roughly 23 or 24 years before the dawn of the #MeToo movement, it might be the best “most men are cruel and abusive animals, and especially the alcoholic ones” movie I’ve ever seen.

I didn’t experience even a twinge of my usual “okay, here we go again with another serving of rote anti-male diminishnent”…I believed every scene, every line, every plot pivot. It may be the best Hollywood-produced feminist film ever made. I trusted every frame.

It’s almost certainly Hackford’s finest effort, and Beristain’s shifting color schemes (Fuji amber for flashbacks, cold grays for present tense) are truly mesmerizing.

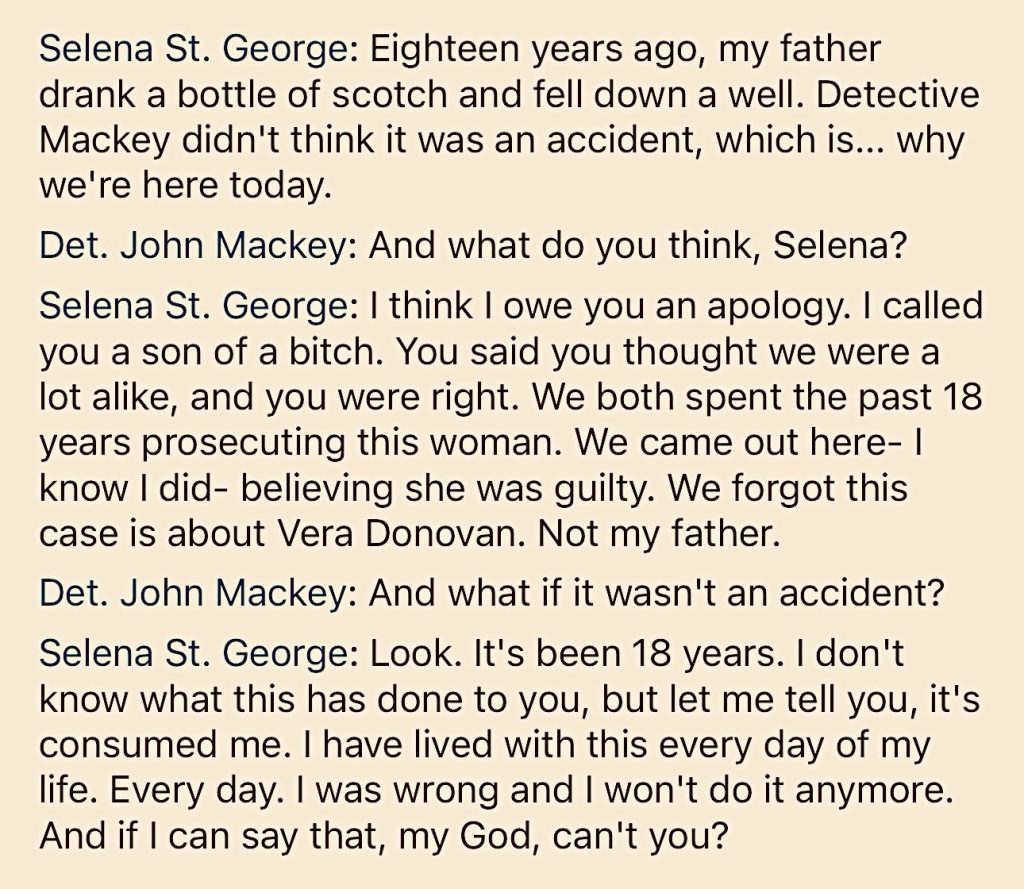

Gilroy’s dialogue is so well-honed and soothingly concise and bracingly articulate.

The co-lead performances by the 46-year-old Bates, whose titular tour de force should’ve won a second Best Actress Oscar in the wake of her startling Misery breakout, and the 32 year-old Jennifer Jason Leigh are keepers. Ditto the supporting David Straitharn, Judy Parfitt, Christopher Plummer and John C. Reilly.

Adapted from Stephen King’s same–titled, best–selling 1992 novel, this Castle Rock production is an exceptionally well-crafted melodrama (almost a kind of realism-based horror film) of the highest calibre…you’re never unaware that you’re chest-deep in a totally classy, #MeToo-ish truth testament made by grade-A people. Because the film is so deftly assembled and therefore persuasive and compelling, Gilroy’s altered adaptation (King’s book was one long first-person confession by Claiborne) isn’t as downerish as it sounds on the surface. And yet it’s basically about small-town confinement, suppressive conditions, domestic misery and exceptional spousal cruelty and abuse, dysfunctional family trauma, incest and blessed revenge.

The final half-hour really pays off in a way that top-tier films used to pay off in the old days (i.e., before the horror of Marvel and D.C., before Stalinist-woke narratives, before streaming multi-part sagas for couch potatoes).