Despite what Variety‘s Brent Lang claimed yesterday, Andy Muschietti‘s It is not the highest-grossing horror film of all time, and it sure as hell hasn’t out-grossed William Friedkin‘s The Exorcist.

Lang wrote that if you bypass inflationary calculus, It‘s domestic gross of $236.3 million tops The Exorcist‘s domestic tally of $232.9 million and is therefore, narrowly defined, the all-time champ. Except you have to apply inflationary calculus, and with an inflation rate of 453% having occured between 1973 and today…well, figure it out.

If you toss out Lang’s Exorcist tally of nearly $233 million and concentrate solely on theatrical revenues from the original ’73 and ’74 run, the domestic Exorcist gross was $193 million. In 2017 dollars that’s $1,067,233,490, or $67 million north of $1 billion. It‘s drawing power is far from spent, but right now The Exorcist‘s ’70s tally is over four times higher than It‘s current gross.

The most accurate measure of the popularity of any film is, of course, admissions. I haven’t time to research those statistics right now (have to catch a noon train back to NYC) but perhaps the readership can dig into it in the meantime.

There’s also the indisputable fact that It sucks and The Exorcist is a masterpiece, at least by the relative standards and criteria of the horror genre. 44 years ago it was regarded by critics as a piece of brutal, assaultive manipulation, but on a contemporary side-by-side basis it’s obvious that Friedkin’s film is head and shoulders above the chain-jerk, shock-and-boo tactics of It.

From HE piece called “Bygone Sensibilities,” posted on 6.26.15:

A few days ago and for no timely reason at all A.V. Club‘s Mike Vanderbilt posted a piece about original reactions to William Friedkin‘s The Exorcist, which opened in December ’73. It reminds you how jaded and cynical the culture has since become. The Exorcist gobsmacked Average Joes like nothing that they’d seen before, but you couldn’t possibly “get” audiences today in the same way. Sensibilities have coarsened. The horror “bar” is so much higher.

But there’s one thing that 21st Century scary movies almost never do, and that’s laying the basic groundwork and hinting at what’s to come, step by step and measure by measure. Audiences are too impatient and ADD to tolerate slow build-ups these days, but Friedkin spent a good 50 to 60 minutes investing in the reality of the Exorcist characters, showing you their decency and values and moments of stress and occasional loss of temper, as well a serious investment in mood, milieu and portents. It had the trappings of class — a genuinely eerie score, flush production values and the subdued, autumnal tones in Owen Roizman‘s cinematography. It was only in the second hour that the shock-and-awe stuff began.

If It had waited 50 to 60 minutes before delivering the really scary stuff, it would have died the first weekend. You know it and I know it. Today’s audience simply wouldn’t tolerate such a strategy.

The best parts of The Exorcist don’t involve spinning heads or pea-soup vomit. I’m talking about moments in which scary stuff is suggested rather than shown. The stuff you imagine might happen is always spookier.

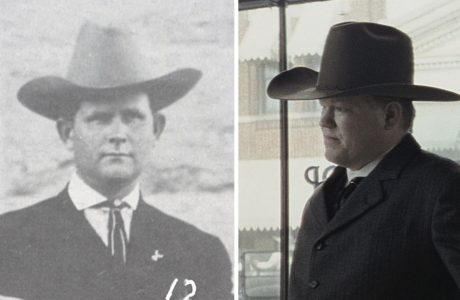

Such as (1) that prologue moment in Iraq when Father Merrin (Max Von Sydow) is nearly run over by a galloping horse and carriage, and a glimpse of an older woman riding in the carriage suggests a demonic presence; (2) a moment three or four minutes later when Merrin watches two dogs snarling and fighting near an archeological dig; (3) that Washington, D.C. detective (Lee J. Cobb) telling Father Karras (Jason Miller) that the head of the recently deceased director Burke Dennings (Jack McGowran) “was turned completely around”; (4) Karras’s dream sequence about his mother calling for him, and then disappearing into a subway; (5) that moment when Regan MacNeil (Linda Blair) mimics the voice and repeats the exact words of a bum that Karras has recently encountered — “Can you help an old altar boy, father?” My favorite bit in the whole film is that eerie whoosh-slingshot sound coming from the attic.

The social impact stuff is all in the above video, of course, but listen to this senior usher at Westwood’s National Theatre talking about people fainting and having to be brought around by smelling salts, and also another employee, Cathy Hewitt, talking about the resilience of audiences as they stood in line for hours on end, sometimes even in the rain. They’re describing a culture and a sensibility that seems as quaint and bygone as that opening narration in Orson Welles‘ The Magnificent Ambersons when he talks about how people used to get around by horse and buggy and took their time and never seemed to be in too much of a hurry.