In a Promising Young Woman thread, I noted this morning that ’20 and early ’21 have been an especially weak year for the kind of rich undercurrent award-season films that less–than–woke, middle–class people (including X–factor types like myself) tend to respond to and pay to see.

For since wokeness began to take hold in ’18 and certainly since the pandemic struck 13 months ago, the movie pipeline has been losing steam and under-providing, to put it mildly. Nothing even approaching the level of Spotlight, Manchester by the Sea, Call Me By Your Name, Dunkirk, Lady Bird, La-La Land, the long cut of Ridley Scott‘s The Counselor, Zero Dark Thirty or Portrait of a Woman on Fire has come our way from domestic filmmakers. **

Above and beyond an array of pandemic suffocations, a significant reason for the strange absence of robust cinema, for this general faint-pulse feeling, is (wait for it) wokeness and political terror.

Wokeness might be good or (sadly) necessary for social change, but it’s not much of a propellant for the creation of knockout award-season flicks that really reach out and touch Joe & Jane Popcorn.

The bottom line is that the erratic pursuit of sweeping, penetrating, soul-touching art (a rare achievement but one that has occasionally manifested over the decades) has been more or less called off, it seems, because such films or aspirations, in the view of certain #MeToo and POC progressives, don’t serve the current woke-political narrative.

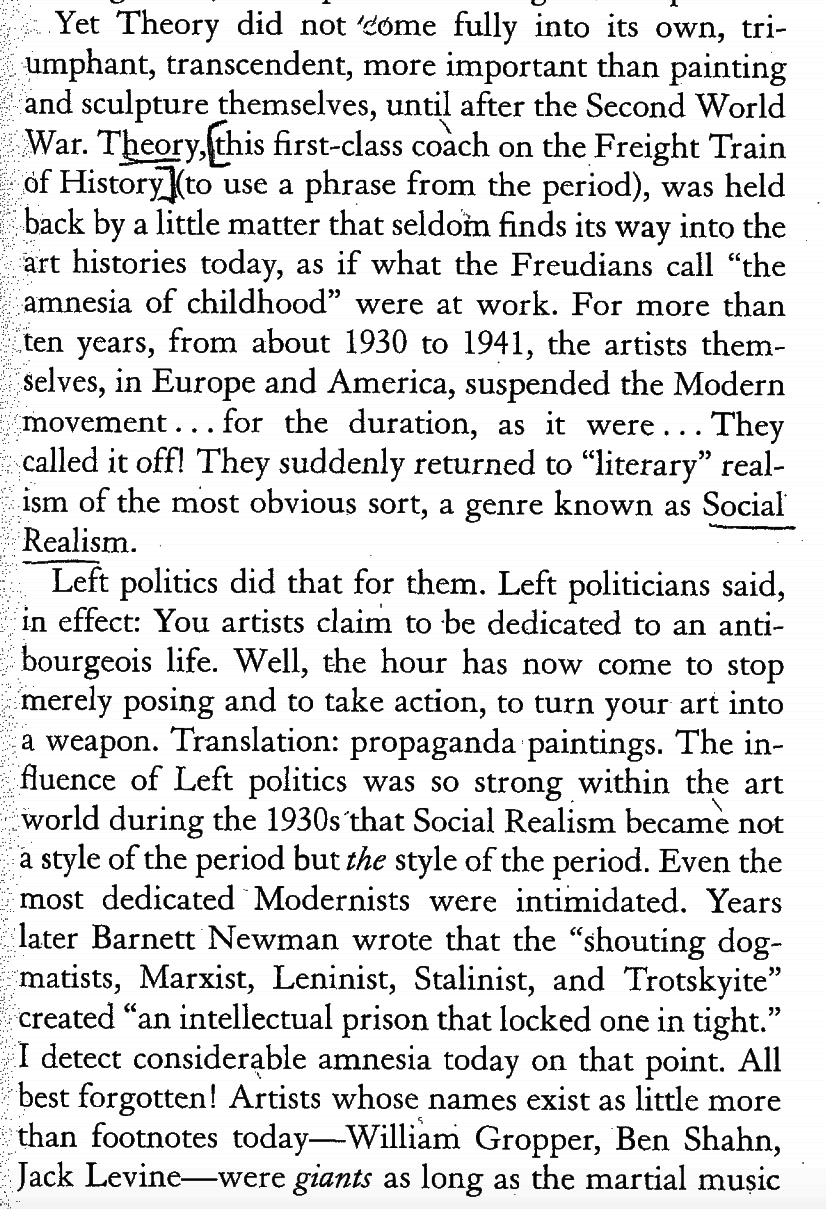

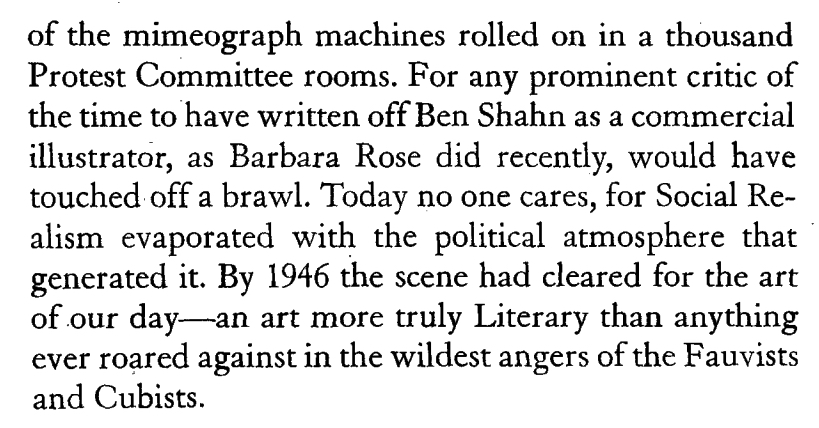

You can dismiss the previous three paragraphs as a typical, broken-record HE rant. But there is, in fact, a historical precedent for what’s going on right now, and it’s nicely recounted on page 30 and 31 of Tom Wolfe‘s “The Painted Word“.

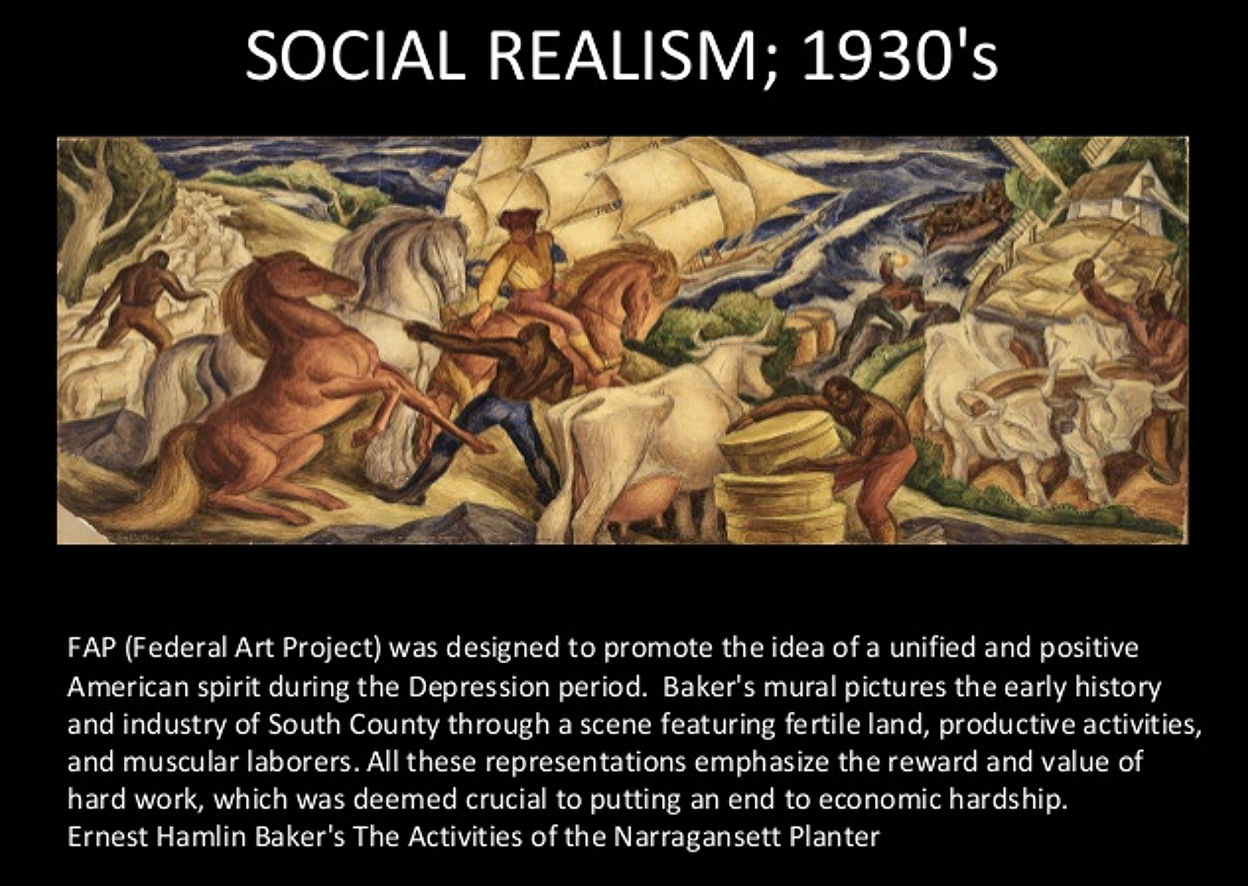

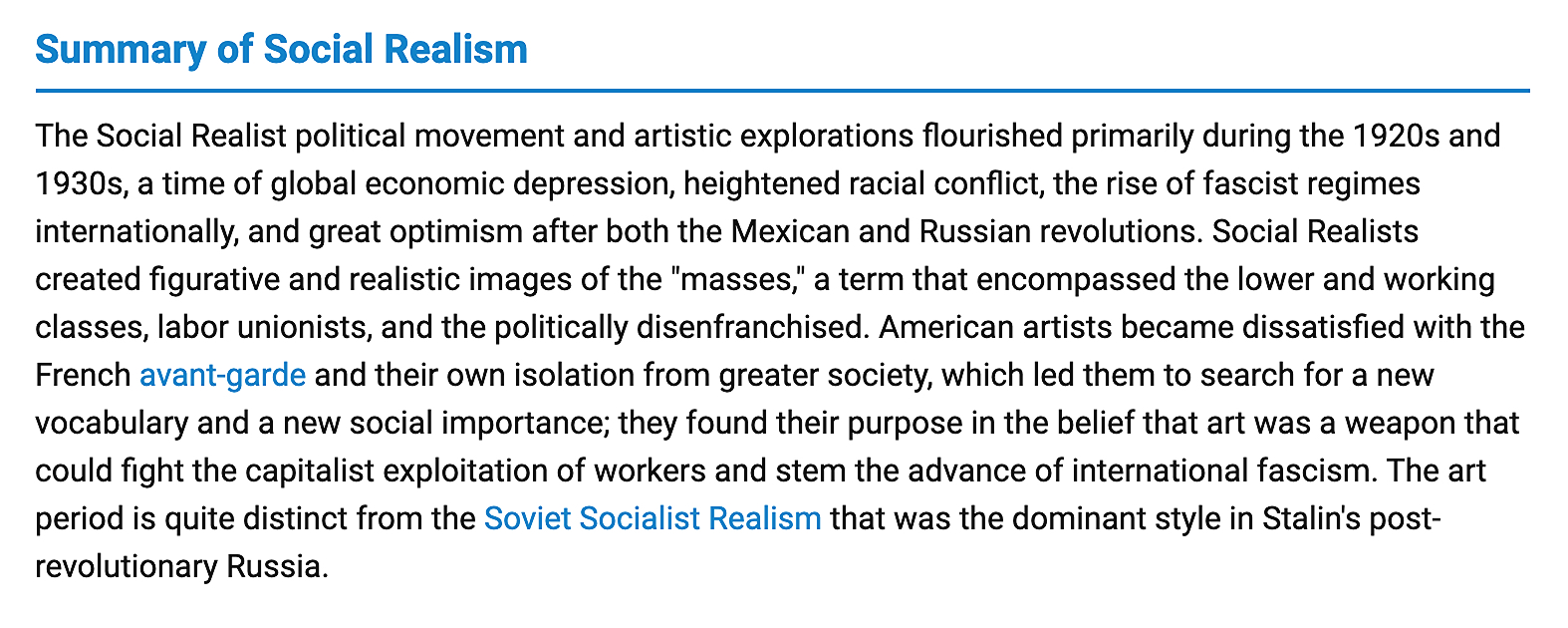

The passage is only two paragraphs long. Would you like to read it? Because what happened in the modern art world in the 1930s — i.e, the dominance of “social realism” — precisely mirrors what’s going on today.

For upscale, sensitive-person, social-reflection dramas have fallen under the influence of a new form of ’30s social realism and, it could certainly be argued, are being used to illustrate and argue against social ills that wokesters regard as evil and diseased. The result has been a new form of enlightened propaganda cinema. (Feel free to supply your own examples.)

It’s almost astonishing to read Wolfe’s description of the “social realism” movement of the ’30s because the same damn thing is happening right now.

For the making of cinematic art, like canvas art of the ’30s, has been more or less (or at least partly) “called off” in favor of serving the woke/thought revolution. For film artists of today, to paraphrase an old Barnett Newman observation about the ’30s, are residing “in an intellectual prison that [locks them] in tight.”

Read the following “Painted Word” passage and tell me this isn’t a dead-to-rights portrait of 2021:

** Overseas and south-of-the-border cinema (i.e., Michel Franco’s New Order) is a whole ‘nother thing.