In an Indiewire piece posted earlier today, producer, industry consultant and former Fine Line production executive Liz Manne outed herself as a major anonymous source for a controversial, once-heavily-criticized 1998 Premiere story that described a culture of sexual harassment at New Line Cinema, which at the time was run by Bob Shaye and Michael Lynne.

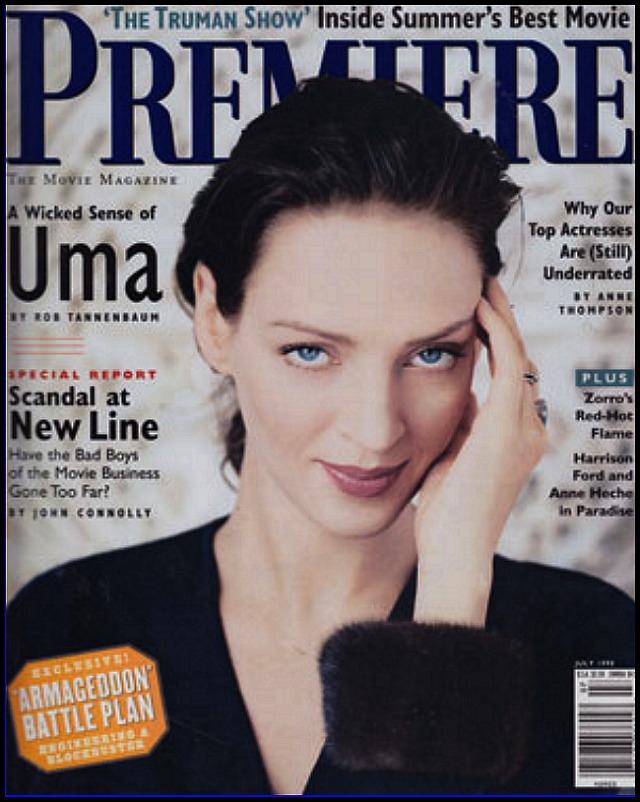

The article, written by John Connolly and fact-checked by Premiere staffers (including then-editor Jim Meigs and senior film editor Glenn Kenny), was called “Flirting With Disaster.”

The article asserted that all kinds of nasty shenanigans (drinking, drugs, sexual harassment) were happening at New Line, and that Shaye and Lynne ran the place “like a college dorm,” according to a producer who spoke anonymously to Connolly. The piece began with a story about a boozy New Line party that happened the year before (1992) at a lodge in Snowmass, Colorado, and about how Lynne made an aggressive sexual pass at an unnamed female executive.

That executive, according to Manne’s Indiewire piece, was Manne herself. As noted, she flat-out admits to having been one of Connolly’s anonymous sources.

In hindsight, the Connolly piece can be appreciated as a tough expose that described a predatory climate that sounds all too familiar by today’s understandings. But because it depended on anonymous sources (when she left the company Manne signed an exit agreement that forbade her from talking to anyone about anything in any context) the article was strongly attacked as an example of reckless or irresponsible journalism.

Two of the attackers were Movie City News’ David Poland and Variety‘s Peter Bart. Coincidentally, there was also a “Reverse Angle” article on page 51 in that same issue of Premiere, written by Harvey Weinstein of all people, that complained about “the reckless use of unnamed sources.”

From Poland’s 6.17.98 MCN article: “Can you say ‘hatchet job?’ I know for sure that Premiere magazine can. It had to be the phrase of the day when it decided to print its story, ‘Flirting With Disaster’” on alleged sexual and drug-related misconduct at New Line Cinema. I am often disgusted with the state of entertainment journalism, but usually it’s because we throw softballs in exchange for access to the talent that sells magazines, newspapers and TV shows. (And yes, some Web sites.) This time, it’s the opposite.

“What was Premiere thinking when it ran the results of John Connolly‘s eight-month ‘investigation’ which added up to little more than a handful of gossipy accusations by unnamed sources that any reporter working this beat on a regular basis could have come up with over a three-day weekend?”

From Bart’s 6.8.98 Variety piece: “A prime example of what’s wrong with anonymous sources appears [in] a Premiere expose on the ‘fast and loose corporate culture’ at New Line, which boils down to a series of character assassinations based on, guess what, ‘anonymous sources.’ Sexual harassment, if and when it occurs, should not be tolerated in any humane company. Having said all this, I think it’s also out of bounds to scorn the mavericks and the nonconformists in our business, even though one can find enough ‘anonymous sources’ to fill a phone book.”

Here are some portions from Manne’s Indiewire piece:

“I was sexually harassed and sexually assaulted by a senior executive at New Line Cinema. At a company retreat in Snowmass, Colo., where we were plied with straight vodka, tequila, Jagermeister — it was like a frat party at high altitude. Shots, shots, shots. Group binge drinking was New Line’s idea of a corporate retreat trust exercise.

“The perp” — an apparent allusion to Lynne, although Manne to this day refuses to name him — “arranged for my room to be near his, in a far, darkened corner of the Snowmass complex. If I persist in viewing him as a human being — not a simple task — I can only imagine he did not fully grasp the terror he inflicted. Perhaps he thought my blowjob was consensual and the beginning of some kind of naughty extramarital affair: an employee ‘with benefits.’

“Within a few short years, I think a half-dozen high-level, female executives quietly left the company. Some quit, some were fired.

“’Women don’t leave New Line. They get carried out in body bags,’ said one senior female executive quoted in a notorious Premiere magazine article about New Line that ran the summer of 1998, six months after I had been fired from the company.

“The day I signed my exit contract, complete with the non-disparagement, confidentiality, and general release clauses required for me to receive the severance, Ben Zinkin, New Line’s chief counsel, tossed the check to me across his big desk. ‘Nice chunk of change, Liz,’ he said. ‘Nice chunk of my life, Ben,’ I returned. I pocketed the check, said goodbye to my crew, and walked out of the office for the last time.

Former Fine Line executive Liz Manne.

“What I realize now, and didn’t then, was that my exit contract from New Line — garden-variety corporate legalese that had nothing to do with my sexual assault or harassment — constituted the real crime against my person. It was a permanent gag (a chillingly apt term) that ensured my enduring status as chattel of a publicly traded multinational media corporation. One man assaulted and harassed me. But it was my fear of an army of corporate litigators that held me enslaved in silence for decades to follow.

“The Premiere article, an investigation of New Line’s notorious, bad-boy, booze, sex-and-drugs culture, was 1998’s film-industry bombshell. It was mostly anonymously sourced, by multiple insiders, including by me, for reasons that hopefully more people might understand today, now that so many women have come forward with their stories that so poignantly describe their wrenching experiences. We survivors made choices of anonymity back in the day; we consented to the tyranny of silence, even as we did not consent to the crimes and damages committed against us.

“From my perspective, the Premiere piece was painfully accurate, though New Line denied it and fought it with vigor. Some of my former female colleagues denied the story in a naïve and enraging letter to the editor. Let me summon some compassion. Some of those signatories were single moms or their family’s primary breadwinners. They had mouths to feed and averted their gaze.

“Competing journalists” — Poland and Bart included — “and many others in the film industry excoriated Premiere and the reporters who investigated New Line. They were skeptical the stories could be true, and felt that even if true, the article had violated some kind of immutable taboo.

“In actuality, like The New York Times today, Premiere was serving the crucial role of the Fourth Estate in a democracy. The article was dismissed as a hatchet job, sour grapes, a cruel grudge fest sourced by failed executives who simply couldn’t thrive in the boys-will-be-boys playground of New Line Cinema. These deniers were unable to wrap their heads around why sources would remain anonymous, and even in anonymity be unwilling, or unable, to describe the gory details of their own trauma.”

If Poland and Bart’s rigorous insistence on using only named sources had been applied by Premiere 19 and 1/2 years ago, the article in question may not have run. Or it might have run in a diluted form. It just goes to show that sometimes, depending on circumstances, using anonymous sources is the right thing to do.