Talk to any impassioned, ahead-of-the-curve film snob about classic westerns, and he/she will probably tell you that Howard Hawks‘ Rio Bravo (1959) is a much better, more substantial film than Fred Zinneman‘s High Noon (1952). More deeply felt, they’ll say. Better shoot-em-up swagger, tastier performances, more likable, more old-west iconic. Many people I know feel this way. And now here‘s director Peter Bogdanovich saying it again in a New York Observer piece — Rio Bravo is even better than you thought, High Noon doesn’t hold up as well, etc.

Something snapped when I read Peter’s article this afternoon. Goddamn it, the Rio Bravo cult has gone on long enough. Bogdanovich calls it “a life-affirming, raucous, profound masterpiece” I’m going to respond politely and call that a reach. I admire Hawks’ movies and the whole Hawks ethos as much as the next guy, but it’s time to end this crap here and now.

High Noon may seem a bit stodgy or conventional to some and perhaps not as excitingly cinematic to the elites, but it’s a far greater film than Rio Bravo.

It’s not about the Old West, obviously — it’s a metaphor movie about the Hollywood climate in the early ’50s — but it walks and talks like a western, and is angry, blunt, honed and unequivocal to that end. It’s about the very worst in people, and the best in a single, anxious, far-from-perfect man. I’m speaking of screenwriter-producer Carl Foreman, who was being eyeballed by the Hollywood right for alleged Communist ties when he wrote it, and receiving a very tough lesson in human nature in the process. He wound up writing a crap-free movie that talks tough, cuts no slack and speaks with a single voice.

You know from the get-go that High Noon is going to say something hard and fundamental about who and what we are. It’s not going to poke along some dusty trail and go yippie-ki-yay and twirl a six-gun. It’s going to look you in the eye and say what’s what, and not just about the political and moral climate in some small western town that Gary Cooper‘s Willl Kane is the sheriff of.

Both are about a lawman facing up to bad guys who will kill him if he doesn’t arrest or kill them first. The similarities pretty much end there.

High Noon is about facing very tough odds alone, and how you can’t finally trust anyone but yourself because most of your “friends” and neighbors will equivocate or desert you when the going gets tough. Rio Bravo is about standing up to evil with your flawed but loyal pallies and nourishing their souls in the bargain — about doing what you can to help them become better men. This basically translates into everyone pitching in to help an alcoholic (Dean Martin) get straight and reclaim his self-respect. High Noon doesn’t need help. It’s about solitude, values…four o’clock in the morning courage.

We’d all like to have loyal supportive friends by our side, but honestly, which represents the more realistic view of human nature? The more admirable?

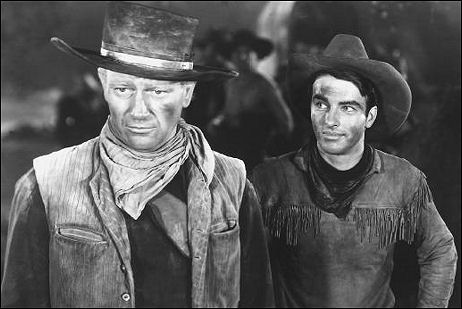

The first 10 or 12 minutes of Rio Bravo, I freely admit, are terrific in the way Hawks introduces character and mood and a complex situation without dialogue. Let it be clearly understood there is nothing quite like this in all of High Noon. I also love the way John Wayne rifle-butts a guy early on and then goes, “Aww, I didn’t hurt him.” But once the Duke and Walter Brennan, Martin, Ricky Nelson and Angie Dickinson settle into their routines and the easy-going pace of the thing, Rio Bravo becomes, at best, a somewhat entertaining sit-around-and-talk-and-occasionally-shoot-a-bad-guy movie.

More than anything else, Rio Bravo just ambles along. Wayne and the guys hang out in the jailhouse and talk things over. Wayne walks up to the hotel to bark at (i.e., hit on) Dickinson. It tries to sell you on the idea of the big, hulking, 51 year-old Wayne being a suitable romantic match for Dickinson, who was willow slender and maybe 27 at the time but looking more like 22 or 23.

Plus the villains have no bite or flavor — they’re shooting gallery ducks played by run-of-the-mill TV actors. Most of Rio Bravo is lit too brightly. And it seems too colorfully decorated, like some old west tourist town. It has a dippy “downtime” singing sequence that was thrown in to give Nelson and Martin, big singers at the time, a chance to show their stuff. Then comes the big shootout at the end that’s okay but nothing legendary.

Does Rio Bravo have a sequence that equals the gripping metronomic ticking-clock montage near the end of High Noon? Is the dialogue in Rio Bravo up to the better passages in Zinneman’s film? No. (There’s nothing close to the scene between Cooper and Lon Chaney, Jr., or the brief one between Cooper and Katy Jurado.) Is there a moment in Rio Bravo that comes close to Cooper throwing his tin star into the dust at the end? Is there a “yes!” payoff moment in Rio Bravo as good as the one in High Noon when Grace Kelly, playing a Quaker who abhors violence, drills one of the bad guys in the back?

Floyd Crosby‘s High Noon photography is choice and precise and gets the job done. It doesn’t exactly call attention to itself, but it’s continually striking and well-framed. To me, the black-and-white images have always seemed grittier and less Hollywood “pretty” than Russell Harlan‘s lensing in Rio Bravo, which I would file under “pleasing and acceptable but no great shakes.”

Dimitri Tomkin wrote the scores for both High Noon and Rio Bravo, but they don’t exist in the same realm. The Bravo score is settled and kindly, a sleepy, end-of-the-day campfire score. High Noon‘s is strong, pronounced, “dramatic” — so clear and unified it’s like a character in itself. And I’ve never gotten over the way the rhythm in that Tex Ritter song, “Do Not Forsake Me O My Darling,” sounds like a heartbeat.

Bogdanovich writes that Rio Bravo didn’t win any Oscars or get much critical respect, but “it was far more popular with audiences than High Noon.” He’s right about this. The IMDB says Rio Bravo earned $5,750,000 in the U.S. when it came out in ’59, and that High Noon brought in $3,750,000 when it played in ’52. Big effin’ deal. High Noon whipsRio Bravo‘s ass in every other respect.

That said, there’s an intriguing Hawks assessment by French director Jean-Luc Godard in the Bogdanovich piece. Godard doesn’t argue that Rio Bravo is pretty much what I’ve described above, but says it’s still a better film than High Noon because — I love Jean-Luc Godard — the exceptionally good things in Rio Bravo can be ignored, and therefore may be unnoticable to a good-sized portion of the audience.

“The great filmmakers always tie themselves down by complying with the rules of the game,” he states. “Take, for example, the films of Howard Hawks, and in particular Rio Bravo. That is a work of extraordinary psychological insight and aesthetic perception, but Hawks has made his film so that the insight can pass unnoticed without disturbing the audience that has come to see a Western like all others. Hawks is the greater because he has succeeded in fitting all he holds most dear into a well-worn subject.”