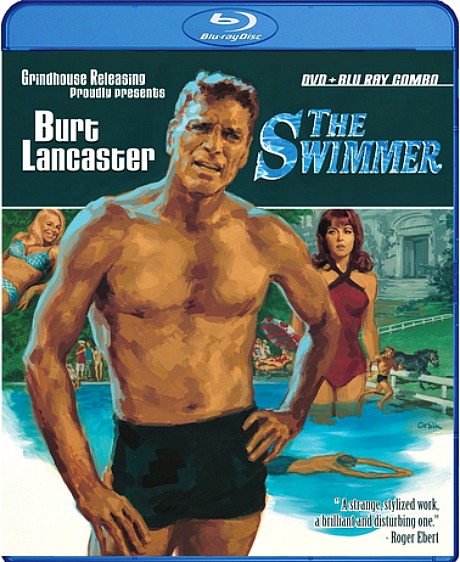

Grindhouse Releasing has a Bluray of Frank Perry and Burt Lancaster‘s The Swimmer (’68) streeting on 3.11. A strange, sterile adaptation of a John Cheever short story that appeared in The New Yorker in July 1964, The Swimmer is easy to admire but all but impossible to like. It has a decidedly cold and spooky vibe. It was shot in the summer of ’66 in Westport, Connecticut — just a town over from Wilton, the leafy hamlet where I was living and half-suffering at the time. I’ve only seen The Swimmer once, but not just because of my own associations — vaguely unhappy memories of failure at school, living under my parents’ rules and regulations, my father’s alcoholism. It’s also that corroded Cheever atmosphere.

Lancaster’s character, a tortured suburbanite who decides to swim across a string of swimming pools in Fairfield County on a journey to his home, is spirited but bluffing — you can tell there’s some kind of tragic history he’s suppressing or hiding from. Like Don Draper he’s all about presenting a “front”, but at least he’s open-hearted and flashing that Lancaster grin. And he looks terrific for a guy of 52 (Burt was born in 1913), wearing only a speedo and looking like a trim 35 year-old.

But with the exception of a blonde teenage girl (Janet Landgard) he befriends and roams around with, the people Lancaster runs into — his “friends” — are ghouls. Their fiendish manner and way of speaking is so curiously “off” that the film gives you a Stepford headache after a half-hour or so. I’ve always regarded The Swimmer as a kind of subtle horror film — a portrait of the stilted values of the World War II “striving class” generation and the alcoholic regimentation that seemed to define suburban affluence back then (similarly portrayed in Ang Lee‘s The Ice Storm and Sam Mendes‘ Revolutionary Road). But The Swimmer is too chilly and creepy — not just lacking in humanity but oxygen.

Read more