Earlier today I saw Dennis Hopper‘s The Last Movie at the Metrograph. The first third is half-interesting so I’m not sorry I saw it, but it’s mostly a sloppy mess, and that’s entirely on Hopper — the director, editor and star. The middle portion and final third are boring for the most part, and at times repellent. I read somewhere that Stewart Stern‘s original screenplay told an actual story that made sense, but the way it’s been cut together is lazy and haphazard; at times it almost feels spazzy. The film is interesting here and there (I liked the “SCENE MISSING” inserts and the fact that the main-title card doesn’t appear until 20 minutes in) but there’s no tension in any of it.

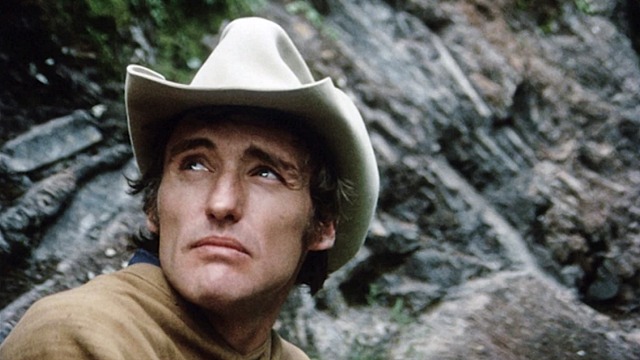

And Hopper’s lead character, a stunt coordinator named Kansas, is just an ass. A weak, squishy, impulsive jellyfish whom you half-tolerate at first, and then you grow to vaguely dislike and then hate him by the end of the first hour. He doesn’t die soon enough.

The Last Movie is set in a Peruvian village (actually a small town named Chinchero) in the Andes foothills. It’s about a Sam Fuller-directed western shooting there, and some guy dying in a stunt accident and Kansas, who seems like a reasonably decent fellow at first, deciding to stay in the village when the film wraps. He hooks up with Maria (Stella Garcia), an attractive, good-hearted woman who may or may not be a prostitute.

Kansas gradually turns into a weasel, breaking poor Maria’s heart by coming on to another woman (Julie Adams, best known for The Creature From The Black Lagoon) in her presence.

Then what happens? Kansas gets worried about running out of funds (this didn’t occur to him when he decided to stay on?) and decides to invest $500 in a sketchy goldmine scheme that quickly goes south. And then some of the native Chincherans — this is the really stupid part — decide to start making their own imaginary film with pretend cameras and microphone booms made of wood, except they don’t understand play-acting and start engaging in real violence. And Kansas gets caught in the wringer.

The primitive-natives thing is patronizing. The locals aren’t some tribe of spear-throwing jungle dwellers but small-town guys who wear boots and jeans and use telephones and order drinks in bars, and yet the movie tells us they’re as clueless and cut off from 20th Century civilization as New Guinea cannibals. A crap premise. Maria is from the same town, remember, and she seems as attuned to the complexities of modern life as anyone. If you don’t buy the idea that the natives are unable to understand the concept of acting and pretending, The Last Movie collapses like a house of cards.

The best part of The Last Movie is the first-act footage of Michelle Phillips, who was around 26 when the film was shot in 1970 and really, really beautiful. My whole mood brightened when I saw her. She married Hopper not long after The Last Movie wrapped, but they got divorced after only eight days. (Married on 10.31.70, divorced on 11.8.70.)

Michelle Phillips during filming of The Last Movie.