I first saw Kenneth Lonergan‘s You Can Count On Me, probably the best written and most affecting sister-brother drama I’ve ever seen, at the January 2000 Sundance Film Festival. I was especially touched by Mark Ruffalo‘s lost-soul character as he resembled my younger brother Tony, who died of an accidental Oxycontin overdose in October 2009.

Two months later I read a couple of reviews of Lonergan’s just-opened The Waverly Gallery, a “memory play” (i.e., one without much of a story). It’s about Gladys Green, an 80-something art gallery manager and woman attorney coping with the ravages of Alzheimer’s disease, and how this burgeoning condition affects her daughter Ellen, son-in-law Howard and grandson Daniel.

Lonergan based it on his grandmother’s deterioration from said disease. The great Eileen Heckart played Gladys to great acclaim; Josh Hamilton played Daniel.

Freshly attuned and excited as I was about Lonergan back then, I remember saying to myself “jeez, where the hell can you go with a play about Alzheimer’s?” I couldn’t imagine anything but a downward trajectory. The family in question can only do their best and tough it out until the end. Especially if they’re determined to not put the Alzheimer’s sufferer into assisted living, which (be honest) is what many if not most families do these days.

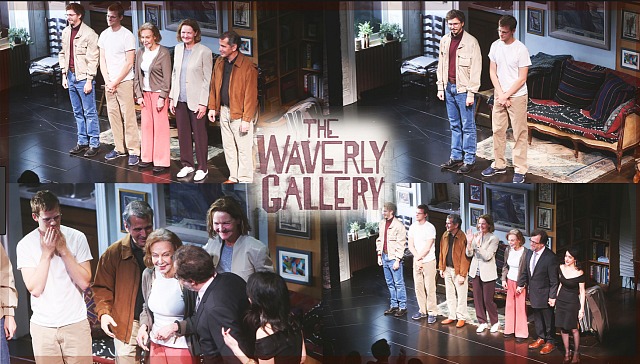

Lucas Hedges, Elaine May in

The Waverly Gallery.

Then again there’s always the nourishment to be had from Lonergan’s excellent writing along with the fact that The Waverly Gallery is a kind of dark comedy.

My initial conclusion was that since there’s nowhere to go with Alzheimer’s plot-wise, the only thing Lonergan could do is somehow persuade the audience that this horrid, godawful disease is a metaphor for the selective memories and occasional delusions that affect all of us from time to time.

How would he do that? Play it dead straight. Recreate this sad, ghastly experience as closely and sharply as he could, get excellent actors to make the characters come to life, and don’t throw in any kind of fake-bullshit upbeat ending.

18 and 1/2 years later or more specifically last night, I saw a revival of The Waverly Gallery at the John Golden theatre on West 45th. I was deeply impressed by Lonergan’s writing, as I knew I would be. And by Elaine May‘s feisty, sharp-as-a-tack performance as Gladys — the last time she was on Broadway was 58 years ago in An Evening With Mike Nichols and Elaine May. (Which was also performed at the John Golden theatre.) And by Lucas Hedges‘ performance as Daniel. And Michael Cera‘s as Don, a not-very-talented painter whose work Gladys hangs in her gallery, and David Cromer‘s as Howard.

I don’t know what to say other than it’s very well done. There was never a second in which I didn’t feel fully engaged and fascinated, and generally delighted to be in the company of all these talented people, director Lila Neugebauer included. This is what a first-rate theatrical sink-in can and should feel like for the most part, I was telling myself.

I just can’t honestly say that I was blown away, but how many times does a stage play manage that?

For The Waverly Gallery isn’t so much a “play” that begins at point A and ends at point C or D, but a meditative memoir that says “you may think your life sucks but wait until you have to deal with a grandmother who’s losing more and more of her mind until there’s almost nothing left, and then she’s deep in the dungeon from which there’s no returning.”

And yet The Waverly Gallery is a seriously composed experience that reminds you of reality in a hundred different ways with a hundred little shoulder taps, and which echoes all over the place.

I’m taken with the following line from Ben Brantley’s 3.23.00 N.Y. Times review: “The language itself ranges from the careful elegance of Daniel’s monologues to lines that find the startling patterns and potency in the rambling speech of senility.”

Thanks so much to David Pollick for helping me with the tickets. The seats were excellent — row G, 102 and 104.