For mostly sentimental reasons, I can’t stop telling myself that the 1992 Cannes Film Festival (5.7 to 5.18) was my absolute personal best. Because it was my first time there and therefore it felt fresh and exotic and intimidating as fuck. I had to think on my feet and figure it out as I went along, and despite being told that I would never figure out all the angles, somehow I did. ‘

It also felt great to be there on behalf of Entertainment Weekly and do pretty well in that capacity. Plus it was the first and only Cannes that I brought a tuxedo to. I’d been told it was an absolute social necessity.

Here are some of the reasons why I’ve always thought ’92 was the shit.

The first time you visit any major city or participate in any big-time event things always seem special and extra-dimensional…bracing, fascinating, open your eyes…everything you see, taste, smell and hear is stamped onto your brain matter…aromas, sights, protocols, expectations, surprises.

Nearly every night I enjoyed some late-night drinking and fraternizing at Le Petit Carlton, a popular street bar. (Or was it Le Petit Majestic?) If you can do the job and get moderately tipsy and schmoozy every night, so much the better. (Or so I thought at the time.) A year earlier I read a quote from P.J. O’Rourke — “Life would be unbearable without alcohol”. I remember chuckling and saying to myself, “Yeah, that’s how I feel also.” Jack Daniels and ginger ale mood-elevators were fun! Loved it!

But not altogether. Four years later I stopped drinking hard stuff; 20 years later (3.20.12) I embraced total sobriety.

I stayed in a gloriously small room (big enough for a queen-sized bed and a dresser) inside the storied, exquisitely comforting, whistle-clean Hotel Moliere (5 rue Moliere 06400 Cannes), and for only $90 or $100 per night. (Something like that.)

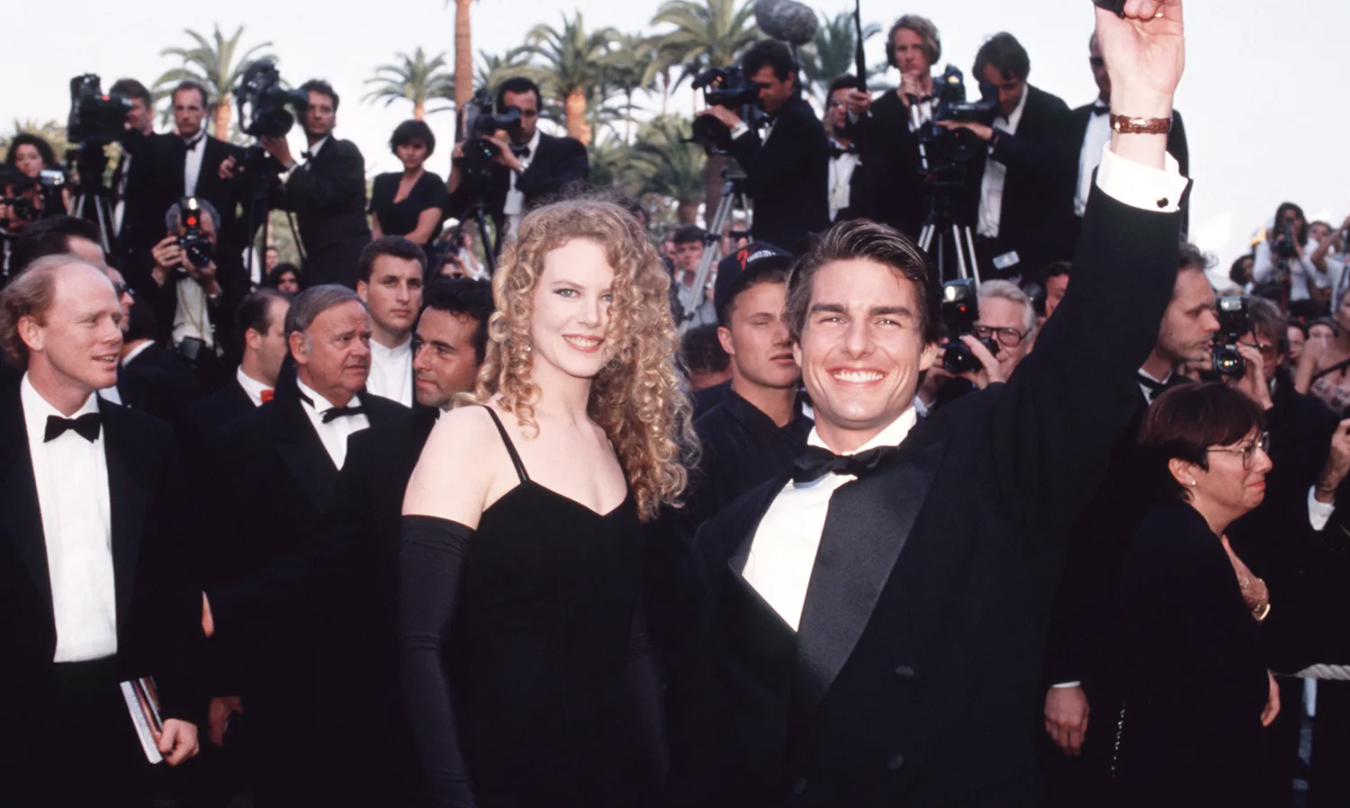

I attended the int’l world premieres of the following films: Quentin Tarantino‘s Reservoir Dogs, James Ivory‘s Howard’s End, Robert Altman‘s The Player (I;d already seen it twice in Los Angeles but still), Abel Ferrara‘s Bad Lieutenant, Tim Robbins‘ Bob Roberts, Paul Verhoeven‘s Basic Instinct, Hal Hartley‘s Simple Men, Abbas Kiarostami‘s Life, and Nothing More…, Baz Luhrman‘s Strictly Ballroom, Vincent Ward‘s Map of the Human Heart…perhaps not the greatest all-time lineup but each viewing felt like a big deal.

I ignored Far and Away — I’d seen Ron Howard‘s period film in Los Angeles a bit earlier, and that was enough.

I met and briefly schmoozed with Tarantino, Verhoeven, Altman, et. al. And attended six or seven cool black-tie parties.