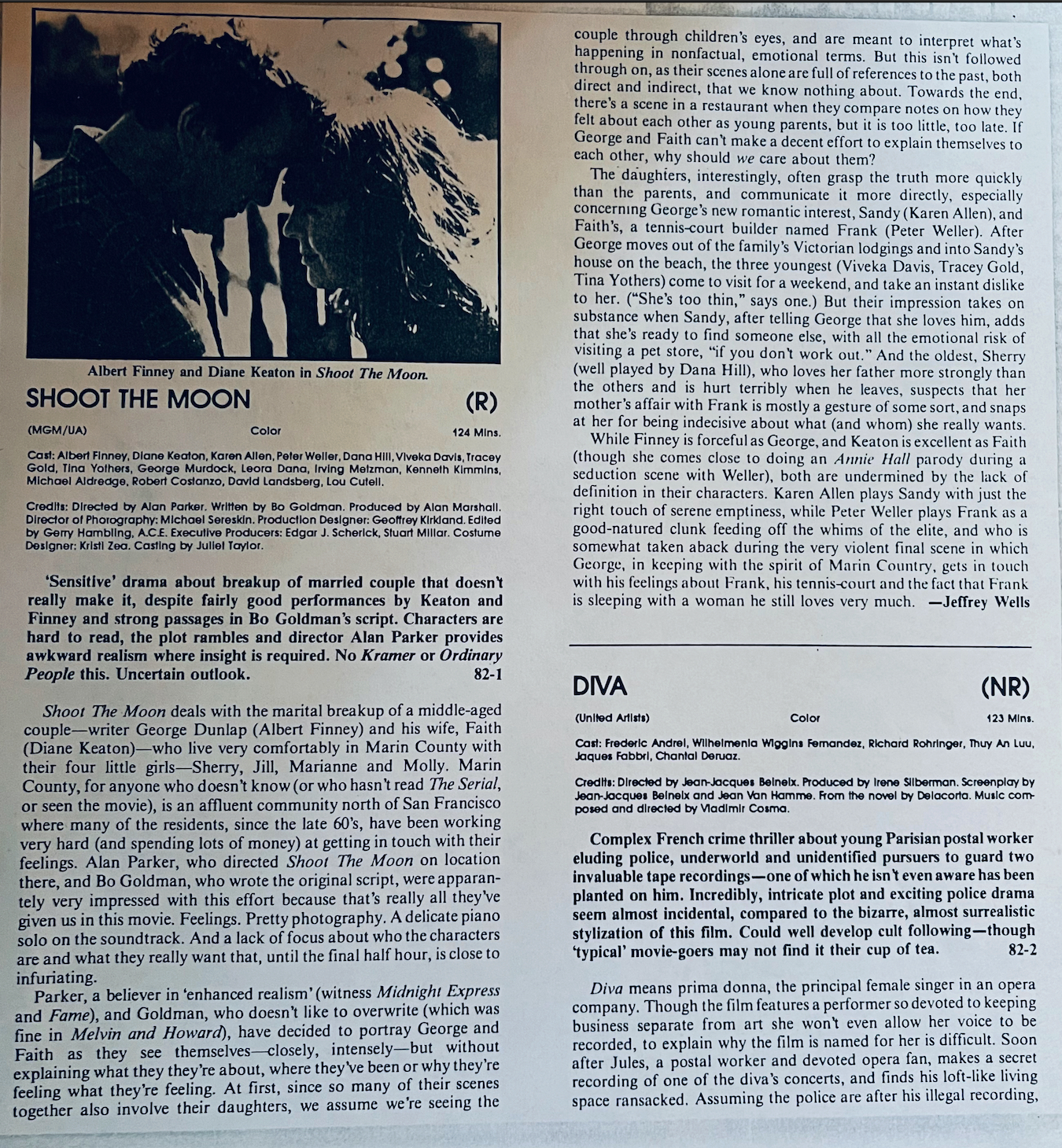

It was apparent earlier today that some are still clinging to the idea that Alan Parker and Bo Goldman‘s Shoot The Moon (’82) is a formidable, first-rate family melodrama. I thought it was a gloomy drag when I first saw it 41 years ago, and I feel the same today. Here’s how I put it on 10.2.21, in the wake of Albert Finney‘s passing:

A few weeks after Finney’s death I re-watched Alan Parker and Bo Goldman‘s’s Shoot The Moon (’82). Not on Amazon, but on the big screen at Hollywood’s American Cinematheque.

It didn’t work out. The film drove me nuts from the get-go, mainly because of the use of solitary weeping scenes (three or four within the first half-hour) and the relentless chaotic energy from the four impish daughters of Finney and Diane Keaton. It was getting late and I just couldn’t take it. I bailed at the 45-minute mark.

The “obnoxious argument in a nice restaurant” scene indicates what’s wrong with the film. It has a striking, abrasive vibe, but it doesn’t work because there’s no sense of social or directorial restraint. If only Parker had told Finney and Keaton to try and keep their voices down in the early stages, and then gradually lose control. Nobody is this gauche, this oblivious to fellow diners.

The balding, red-haired guy with his back to the camera (James Cranna) played “Gerald” in the Beverly Hills heroin-dealing scene in Karel Reisz‘s Who’ll Stop The Rain?.

Which other films aspire to be as relentlessly gloomy as Shoot The Moon? I’m talking about films that give you no mirth, no oxygen. A steady drip-drip-drip of depression, foul moods, anger, downishness.