A distant relation of Foghorn Leghorn?

A distant relation of Foghorn Leghorn?

“Brilliant Burn,” posted on 9.5.08: Either you get, agree with and derive enormous delight from dry misanthropic humor…or you don’t.

Either way, you certainly can’t argue with the fact that while Joel and Ethan Coen have a lot more up their sleeves than just this, for when they’re in the mood to dispense their extremely low opinion of human behavior, they are masters of the form. Nobody knows from dry, diseased and delectably deadpan like these guys. It’s in their bones and their blood.

And it’s the genius of Burn After Reading, their latest, to offer another serving in a way that may seem slight or irksome to some, but it is in fact — I mean this — a major satirical meditation about everything that is empty, wanting, sad and hilariously absurd in these united and delusional states of America.

I didn’t laugh all that much, but I loved every minute of this thing. Relished it. I sat there with a slight smark on my face, chortling every now and then but with all kinds of “yeah, right, exactly, perfect, hah!” stuff happening in my head.

The plot shenanigans are for the popcorn eaters to chew on and the disgruntled critics to bitch about; the meat and marrow of Burn After Reading is contained in the ample and delicious margins. The atmosphere, the asshole-ish line deliveries, the mocking tone, the wacked particulars, and those looks of fear, loneliness, concrete stupidity and desperation.

If you look at it this way, the movie is a feast.

If you’re on the misanthrope boat, this half-espionaged, half-comedic take on modern fools and manners is about as good as this sort of thing gets. But you have to forget about “laughing.” (Which is overrated anyway, despite what Joel McCrea‘s John L. Sullivan might have thought.)

You can sit there and eat your popcorn and take it as a sardonic goofball spy movie crossed with a comedy of errors that doesn’t add up to much, and that’s fine. But the meanest and cruelest jokes aren’t just the funniest, as Mort Sahl once said — they’re also the most thoughtful.

Burn After Reading is not a movie for the ages, but a modest and dead-perfect geiger-counter reading of what ails those desperate, constantly itchy and perturbed Americans in the comfortable urban areas who can’t help but shoot themselves, attack others, make mad lunges at quick money and temporal erotic satisfaction. Prisoners of their swollen egos and limited intelligence.

Strivers who must (they feel) have more, who can’t be satisfied or serene, who eat the right foods, belong to health clubs, drink too much, scheme and claw too much and are natural-born comedians in the eyes of God.

Which is how Burn After Reading starts and ends, by the way — from the point of view of a sad, bemused and occasionally chuckling cosmic super-being.

I haven’t even mentioned the cast — George Clooney, John Malkovich, Brad Pitt, Frances McDomand, Richard Jenkins, J.K. Simmons, David Rasche — or the beautiful note-perfect ending. But them’s the breaks when you’re doing four movies a day plus filing and parties and random chit-chats on the street.

With the Venice Film Festival debut of William Friedkin‘s The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial only a month away, it’s necessary to state here and now that the absolute best shipboard mutiny scene ever filmed can be found in Carol Reed and Lewis Milestone‘s Mutiny on the Bounty (’62).

Yes, better than the mutinies in Roger Donaldson‘s The Bounty (’84), Lewis Gilbert‘s Damn The Defiant! (‘62), Tony Scott‘s Crimson Tide (‘95) and Edward Dmytryk‘s typhoon takeover in The Caine Mutiny (’54).

In its entirety the ’62 Bounty is problematic but the 10-minute mutiny scene, especially between the 1:40 and 3:30 mark, is absolute aces. I especially adore Marlon Brando‘s dashing and authoritative saber-brandishing during the brief, side-to-side tracking shot between 1:55 and 2:05 — the first and only such shot in the entire film.

My second favorite mutiny scene occurs in Howard Hawks‘ Red River (’48).

Friedkin’s film is apparently set during the Gulf War of the early ’90s. The costars include Kiefer Sutherland as Humphrey Bogart, Jason Clarke as Jose Ferrer, Jake Lacy as Van Johnson and Lewis Pullman as Fred MacMurray.

When I was 10 or thereabouts my father played a psychiatrist in a small-town stage production of The Caine Mutiny Court Martial so don’t tell me.

From Fionnuala Halligan‘s Screen Daily review of Golda (2.20.23):

“When an iconic actor portrays an iconic figure, the success or failure of the project tends to depend on the power of the performance blasting away the wigs and prosthetics. Helen Mirren achieves all that while playing Israeli politician Golda Meir. But, in Golda, director Guy Nattiv and writer Nicholas Martin haven’t quite kept up their end of the bargain.

“Dropping the audience into the start of the 1973 Yom Kippur war with the chain-smoking caretaker premier, the film is a tense story of a woman and her generals around a cabinet table over the course of the conflict. Endless cigarette smoke, overflowing ashtrays, maps, a fat suit, a wiry wig, hairy eyebrows, orthopaedic shoes — but who was Golda Meir? The film prefers to avoid her as a human being, swerving into her politics and replaying the war from the perspective of her military cabinet over 10 charged days.”

Posted on 2.29.16: “In a few days Quentin Tarantino‘s New Beverly Cinema will be screening a beware-of-Ryan O’Neal double bill — Love Story (’70) and Oliver’s Story (’78).

“A little more than 37 years ago I laughed at a defaced version of an Oliver’s Story one-sheet on a New York subway station wall. It won’t be very funny if I use the original graffiti so I’m going to use polite terminology. The dialogue balloons had O’Neal saying to costar Candice Bergen, “I’m sorry but may I have sex with you in a way that can’t get you pregnant?” Bergen answered, “If missionary is really and truly out I’d prefer oral.”

“I was poor and struggling and mostly miserable, but the graffiti made me laugh. It still makes me laugh today. I guess you had to be there.”

I was thrown pretty hard by that early Oppenheimer scene with the poisoned green apple. Actually a lethal apple, injected by Cillian Murphy‘s titular character with liquid cyanide. The intended victim is Patrick Blackett (James Darcy), a Cambridge University instructor and physicist whom Oppie despises.

At the very last minute Oppie comes to his senses, realizes that murdering a professor may impact his life adversely, runs back to the classroom and prevents the apple from being consumed. Except the guy who almost bites into it isn’t Blackett but Danish physicist Niels Bohr (Kenneth Branagh).

Post-injection my immediate thoughts were (a) “the fuck?”, (b) “What kind of loose-cannon psycho twerp is this asshole? Who does this kind of thing?”; (c) “Oppie almost killed once so who’s the next possible victim? Will he strangle Florence Pugh‘s Jean Tatlock after having sex with her? Will he stab Robert Downey, Jr.‘s Lewis Strauss in the back of the neck with an icepick?

Once you’ve opened the Pandora’s Box of premeditated murder, character-wise you can’t close it. And so the cyanide apple half-hovers over the entire film. Or it did for me, at least.

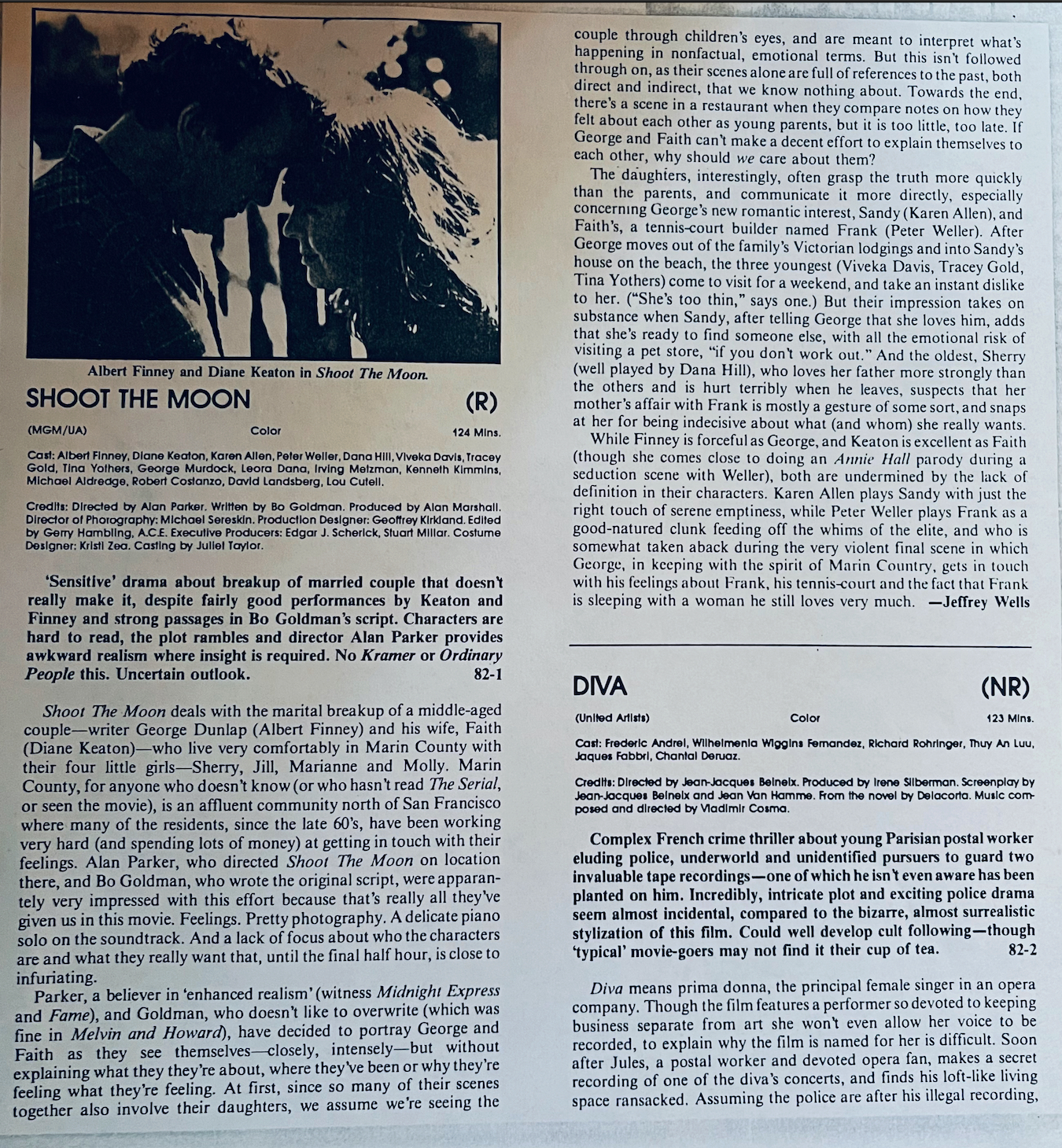

It was apparent earlier today that some are still clinging to the idea that Alan Parker and Bo Goldman‘s Shoot The Moon (’82) is a formidable, first-rate family melodrama. I thought it was a gloomy drag when I first saw it 41 years ago, and I feel the same today. Here’s how I put it on 10.2.21, in the wake of Albert Finney‘s passing:

A few weeks after Finney’s death I re-watched Alan Parker and Bo Goldman‘s’s Shoot The Moon (’82). Not on Amazon, but on the big screen at Hollywood’s American Cinematheque.

It didn’t work out. The film drove me nuts from the get-go, mainly because of the use of solitary weeping scenes (three or four within the first half-hour) and the relentless chaotic energy from the four impish daughters of Finney and Diane Keaton. It was getting late and I just couldn’t take it. I bailed at the 45-minute mark.

The “obnoxious argument in a nice restaurant” scene indicates what’s wrong with the film. It has a striking, abrasive vibe, but it doesn’t work because there’s no sense of social or directorial restraint. If only Parker had told Finney and Keaton to try and keep their voices down in the early stages, and then gradually lose control. Nobody is this gauche, this oblivious to fellow diners.

The balding, red-haired guy with his back to the camera (James Cranna) played “Gerald” in the Beverly Hills heroin-dealing scene in Karel Reisz‘s Who’ll Stop The Rain?.

Which other films aspire to be as relentlessly gloomy as Shoot The Moon? I’m talking about films that give you no mirth, no oxygen. A steady drip-drip-drip of depression, foul moods, anger, downishness.

The downside being that Elvis Presley is played by a towering, Paul Bunyan-sized Jacob Elordi, and lead protagonist Priscilla is played by a nearly dwarf-sized Cailee Spaeny.

The Barbera quote is from a 7.25 Deadline interview, posted by Andreas Wiseman.

From Richard Brody‘s 7.26 review of Chris Nolan‘s Oppenheimer:

Thanks all the same but that’s still a hard “ixnay.”

After much thought and consternation I’ve decided that grief recovery dramas are a bad thing to wade into, and that they’re actually a sub-genre of sorts…a shamelessly whorish one.

And that’s not a putdown of Manchester From The Sea because Casey Affleck doesn’t recover from grief at the end — he’s stuck in the swamp and will never climb out.

The only grief recovery drama I’ve truly admired is Robert Redford‘s Ordinary People (’80) — the sadness in that film gets me each and every time.

Otherwise I’ve had it with this genre. HE to grieving characters: I’m not saying “snap out of it!” like Cher in Moonstruck, but I am saying i’ve no interest in holding your clammy hand as you moan and writhe and quake with sorrow.

Note: I’m not referring to real life and actual grief, of course, but to the exploitation of same by the wrong people.