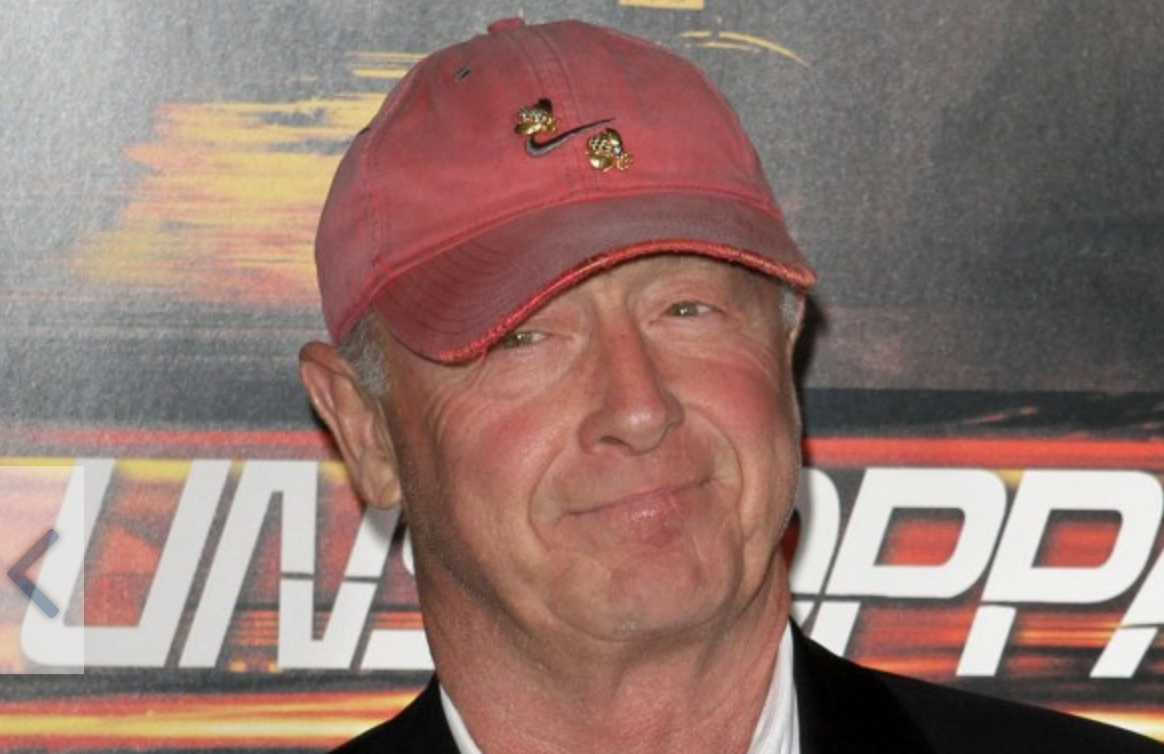

On 5.20 former Paramount and Disney production chief David Kirkpatrick posted a fascinating Facebook essay about working with fabled director Tony Scott (1944-2012) on Top Gun (’86).

“Original Top Gun helmer Tony Scott was to have directed Top Gun: Maverick. Tony had a signed contract with Paramount and was developing the screenplay. But ten years ago this August, Tony jumped off a San Pedro bridge to his death. I am not certain of the whys behind the suicide**, only that it is always a sad event when someone checks out early. It’s especially sad when it is someone as sunny, bull-headed, and easy-to-laugh as Tony. He silently battled cancer for 40 years but kept it quiet. There was no sign of it in the coroner’s report or any other underlying health issues. His brother, Ridley, called his suicide ‘inexplicable.’

“I first met Tony on the screen. He was a lad of 15 years. He starred in his older brother’s first experimental film. It was shot with a Bolex in Hartelpool England. The movie was called Boy & Bicycle — 45 minutes of Ridley Scott doing fancy camera moves while Tony rode around. It was not as powerful as Truffaut’s first film which also tackled the subject matter of bicycles, but it showed the daring and power of the film language that Ridley would later command in movies from Alien to Blade Runner to Gladiator.

“Tony had a sweet demeanor in that short movie. While he was 8 years older than I, I always treated him like a younger brother. What does that mean? I was kind but firm with him because he could be prone toward mischief and disobedience even while smiling and hugging you.

“In the flesh, I first met Tony in an interview with Ned Tanen, the head of the studio, at Ned’s house in [Santa Monica] on Channel Road. The meeting was to determine if Tony should direct Top Gun. During the high-tension meeting, Tony fell asleep. In mid-sentence. While explaining his vision in Ned’s favorite chair.

“35 Hollywood directors had turned down Top Gun. The producers, Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer, were anxious to keep the project alive. But NO ONE wanted to get near it. Don and Jerry had a monster hit with Flashdance. BUT when first viewed, Flashdance was a hot mess. After the preview, the theatre was empty. The audience had walked out. It was that bad. Flashdance went through 35 arduous previews until it morphed into an audience-pleasing juggernaut success. Paramount was infamous for previewing until the movie was the best it could be.

“After the meeting with Scott, Tanen turned to me and said ‘well, what do you want to do?’

“Then came the most important prompt of my life. I learned so much through that prompt. Ned said, ‘Listen, I hate this fuckin’ project. I hate these fuckin’ looney-tune producers. Everyone in town hates the script. But I believe in you. If you want to make a fuckin’ movie with this Brit who falls asleep in the middle of a job interview, then be my fucking guest. You make the decision, right or wrong. And when this fucking movie comes out, you’re going to wear it, for better or worse. You get it? Do you understand me?’

“I took up the gauntlet. To be fair, Scott was jet-lagged. He had gotten off a plane from London and was rushed to Ned’s house for the meeting. I felt bad for my younger brother.

“That night, I booked a projection room on the Paramount lot, ordered some take-out, and watched Tony’s last movie, The Hunger, about lesbian vampires. It was beautiful to look at, and it was godawful. Commercial storytelling demands that a director put the energy of the narrative in the right place. It was a bunch of pretty images and nothing more.

“In The Hunger, Tony was so focused on closeups of high heels and red-painted mouths and endless fluttering curtains, I never had a clue where I was in the story. He never established the geography of the narrative. There were no masters. No exits and entrances of people into rooms. Where the heck were we?

“After a sleepless night, I asked to have breakfast with Tony and his manager, Bill Unger. I explained to Tony that we would hire him to direct Top Gun under two conditions: 1) adhere to the budget of $13.5 million and 2) in every scene, shoot a master up front as protection. ‘We have to know where we are, Tony. You are a brilliant shooter but we have to know where we are. If we are shooting a bar scene, we need to see the bar to establish the scene. That goes for every scene, whether it be an air hanger or a classroom. ‘I promise, mate,’ he said as he smiled and hugged me.

“I went back to Tanen and told him we had found our man. I explained why we were hiring him, what the simple strategy of obtaining master shots in each scene. I told Ned that I had gone over the financials and believed with some certainty, with Tom Cruise’s star power, we could reach at least break-even if the picture did $50 million in U.S. box office. With that box office, we should do at least 3 million units in home video.”

Tanen: ‘Listen to you,’ he laughed. ‘You’ll have my job in 3 years.’

“’I appreciate the responsibility and for your belief in me,’ I said. ‘No one has ever believed in me like that.’

“’Get outta here,’ he said but he was choked up. Three years later, I took over his job. He was tired of it. Ned helped me believe in myself. I never worked so effing hard to make Tony work as the director in all my life.

“A note about Ned. He had a great take on young people. At Universal he had made Breakfast Club, Animal House and The Blues Brothers. At Paramount, he was responsible for the John Hughes movies and supported the music-driven movies that had become a part of Paramount brand…Saturday Night Fever, Flashdance, Footloose. Top Gun was also a young, music-driven picture. Coming off of Risky Business, Tom Cruise was red-hot. Ned agreed to pay him $1 million dollars, unheard of for such a young star. Ned also agreed to pay the same one million to Matthew Broderick to star in Ferris Buehler’s Day Off.

“Tony Scott was a creative lad. He was headstrong and determined but always charming and positive. When we refused to give him extra money to decorate Kelly McGillis’s porch, he got the owner of a shabby chic-like store in San Diego to open its doors in the middle of the night so he could buy pillows for the day’s shooting. I remember showing up on the location in Miramar. He positioned the pillows on the benches with such love, checking them against the camera frame.

“By week #4, I had fired Tony two times. He forgot his promise on the establishing shots and I got tired of it. When he got to shooting the cockpit-to-cockpit shots, we could never see faces, only clouds through the visors. ‘No one is going to know who the characters are! How are we going to tell Goose from Maverick?’ I shouted. ‘Subtitles,’ he replied. ‘No subtitles in this movie!’ I replied. I was so angry at him. He kept shooting visors with clouds in.

“The third time I fired him, it was by fax — a letter [that the] egal [department] had drafted, which contained all the DGA protocols. I tipped off the producers and they played along. They had to keep peace on the set. I would be the bully-brother. In the middle of the night, Tony appeared at my apartment door in Westwood as I wouldn’t pick up the phone. He promised and pleaded for one last chance. ‘Okay, okay! I promise! No visors or you can have my balls.’ He was crying. I looked at him sternly. I was the only one guy who knew the truth about his health as I had to deal with the reinsurer. ‘Okay, you can have my one ball.’ He had lost the other to the Big C. ‘You know I’ll take it, if you fuck me over on this.’

“He didn’t. He shot the whole three-day sequence again, without visors.

“We had an amazing arrangement with the Navy. The Navy gave us everything for free. Everything. I had made An Officer and A Gentleman three years earlier without the support of the Navy (they didn’t like the DI swearing so much but the actor who played the character, Lou Gossett, won the Academy Award). BUT when Officer came out in 1982, recruiting went crazy. The Navy cut its marketing budget because An Officer and a Gentleman was doing all the recruiting for them. So when we planned to make Top Gun, the Navy liason, John Horton, the unsung hero of Top Gun, rolled out the red carpet.

“The only thing Paramount had to pay for was the engine fuel for the fighter jets and the air carriers. Tony was a brilliant shooter. Like his older brother, he came from commercials. It was all about lighting for Tony, especially ‘magic hour’ at dawn and dusk whenever grows beautiful in rose or golden light. Like a game of Risk, Tony moved the jets and the carriers around like pawns to capture the right sunsets and sunrises. It became a problem. Since he wouldn’t stop, I charged him for the fuel. He wrote checks every day for the extra fuel. By the time we were finished shooting, he had written personal checks to the tune of $437,000. His fee was $400,000.

“After the picture came out, Paramount returned the money to Tony for the fuel and for the porch pillows. Tony’s first participation check was in the millions. Ned gave me a nice bonus check too. When I purchased my first house, a box arrived at the door. It was from Tony — the pillows from Charlie’s porch.

“After Tony’s tragic death, Ridley dedicated several movies to him. His family created a scholarship with the American Film Institute in his honor, ‘to help encourage and engage future generations of filmmakers.’

“As for his headstrong behavior on Top Gun, Tony Scott was simply being an artist. He was playing the role of Maverick, rebellious as hell and attempting to capture that essence in the film. Top Gun: Maverick is dedicated to the memory of Tony Scott.

For anyone interested, here’s a clip from Boy & his Bicycle.

** Kirkpatrick knew Tony had been afflicted with testicular cancer in the ’80s and he doesn’t know why he killed himself? Kirkpatrick has surely been told by now that Scott was suffering from terminal brain cancer. A leather-goods repair guy in Beverly Hills whom Scott was a loyal customer of (Scott’s autographed photo was on his wall) told me what he believed about Tony’s affliction, and I believed him.