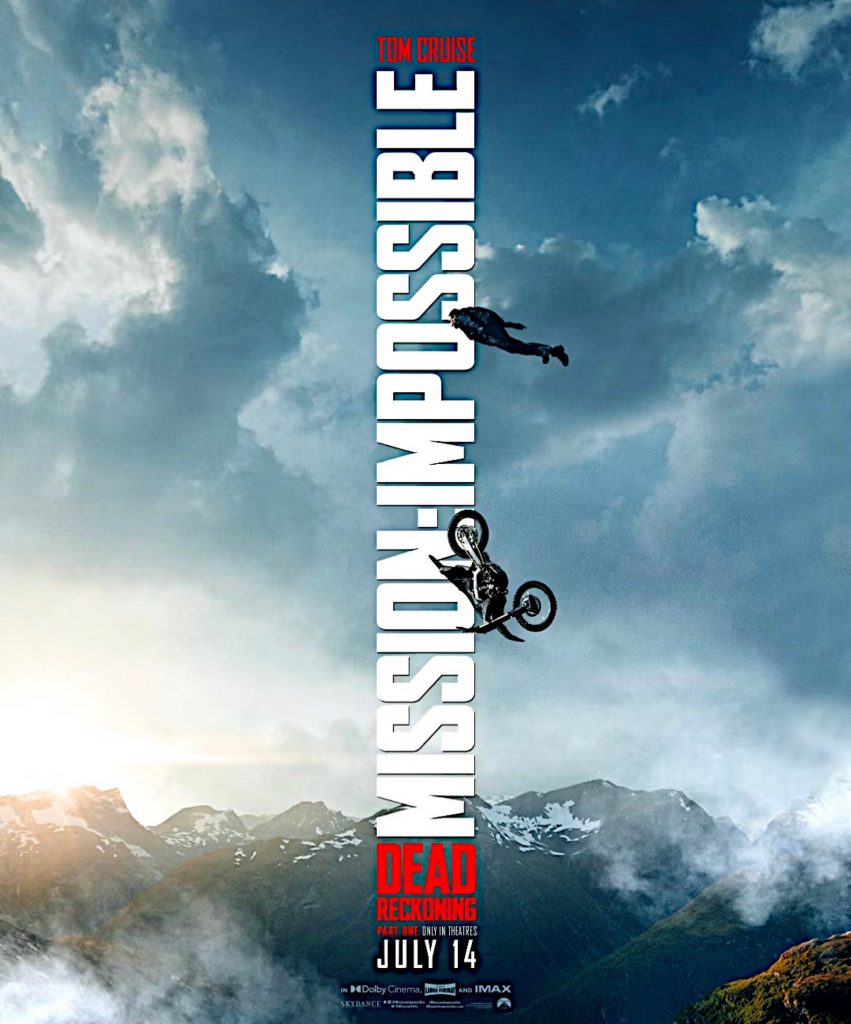

Tom Cruise is fine but the bike is doomed…totally doomed to fall 1700 or 1800 feet and crash on the rocks below…smashed, shattered and mangled to death…forever ruined…a terrible way to die.

Addison DeWitt to Eve Harrington near the end of All About Eve (’50): “That I should want you at all suddenly strikes me as the height of improbability. But that, in itself, is probably the reason. You’re an improbable person, Eve, and so am I. We have that in common. Our contempt for humanity, an inability to love and be loved, insatiable ambition, and talent. We deserve each other.”

In short, not only was DeWitt straight but he ended up putting the high hard one to Anne Baxter‘s Eve Harrington on a nightly basis, and sometimes twice on Sundays

Rather than attempting to predict, HE prefers to lament, applaud, dispute, protest, cheer, weep and take potshots as the show moves along.

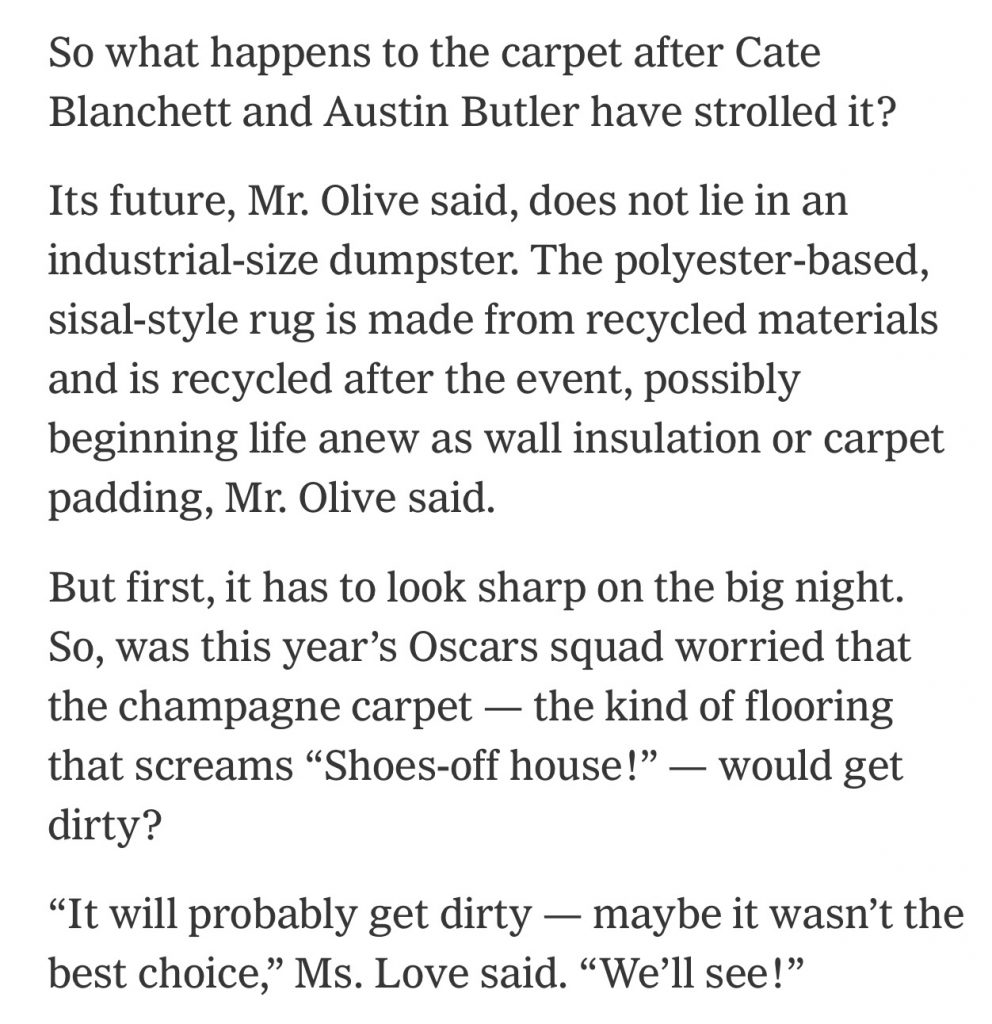

If I was running the show I would say to all the gown designers and fashion consultants who’ve complained that traditional arterial crimson red doesn’t blend well with certain colors…I would say to them “gee, that’s too bad, I’m sorry to hear this but my answer is “tough shit and you can all kiss my ass because the red carpet is staying.”

From Sara Bahr’s 3.10.23 N.Y. Times story:

Since Thursday I’ve been dog-sitting in West Orange while Jett, Cait and Sutton are in Massachusetts for a weekend funeral. Joey, a pit bull with a bum hind leg, and Luna, a sausage beagle, are both older but they love me and I them.

But they insist on fairly close proximity and almost constant affection at all times, and after three days and nights I’m exhausted from lack of sleep due to sharing the guest room bed with these guys as they take up most of the mattress space. Three nights of bad sleep, mainly due to Joey.

Right now I’m trying to get a little extra shut-eye (I was up half the night from the sprawling bodies and dog farts, plus we just lost an hour to daylight savings) by locking Joey downstairs behind the plastic staircase gate.

And of course, Joey is whining and moaning and banging against the gate as we speak.

Update: Joey has somehow crashed or squeezed through the gate. He’s up here now with us, and of course he’s back on the bed. I love these guys but I’m getting sick of this — I’d like a little peace.

New update: Lying on the couch and of course they have to sleep either right next to me or on top of my legs.

Jett scolding: “U trained them, dad. U give Joey too much love and attention and let him walk all over u. My [disciplined] way may seem cruel but it’s the only way to have any sanity.”

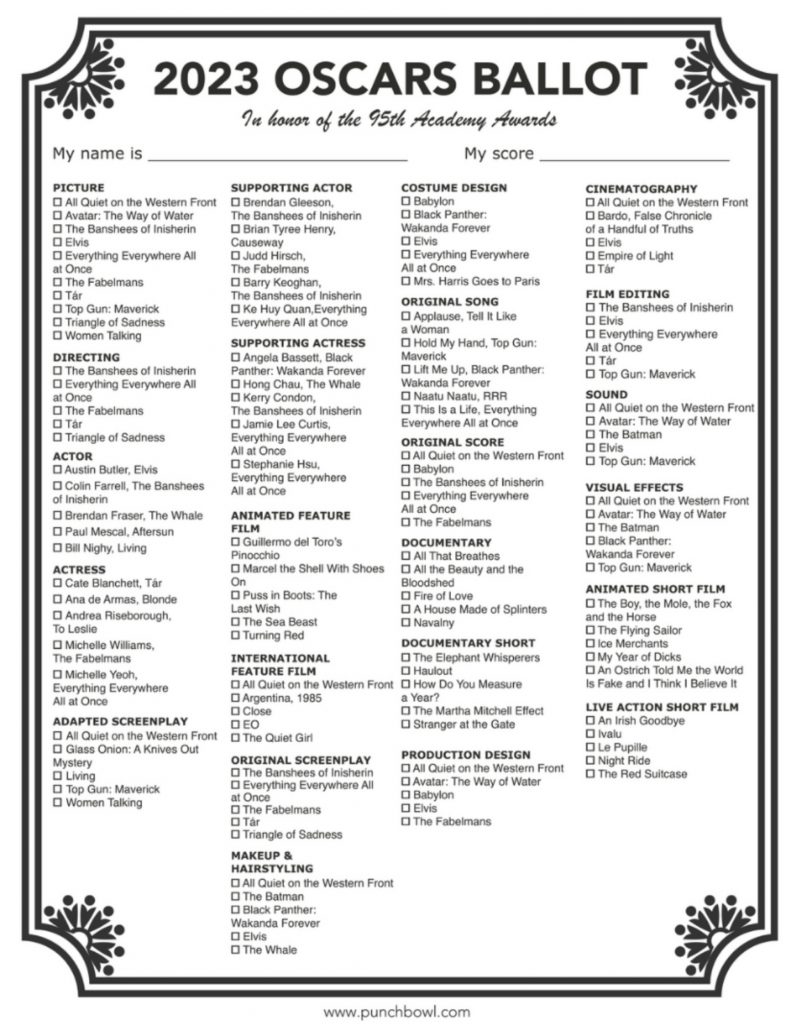

That’s all I’ll be asking for tomorrow night. I’ve accepted that as far as EEAAO is concerned, Sunday night’s grief will be a fallen leaf and I will weep as much (or as little) as necessary. But don’t give the Best Supporting Actress Oscar to Wakanda Forever’s Angela Bassett…please. Condon’s Banshees of Inisherin performance was so rich and real and open-hearted (so far above Bassett’s high–strung histrionics that it’s not even worth comparing the two)…just pan things out in Condon’s favor and I’ll find a way to live with the rest.

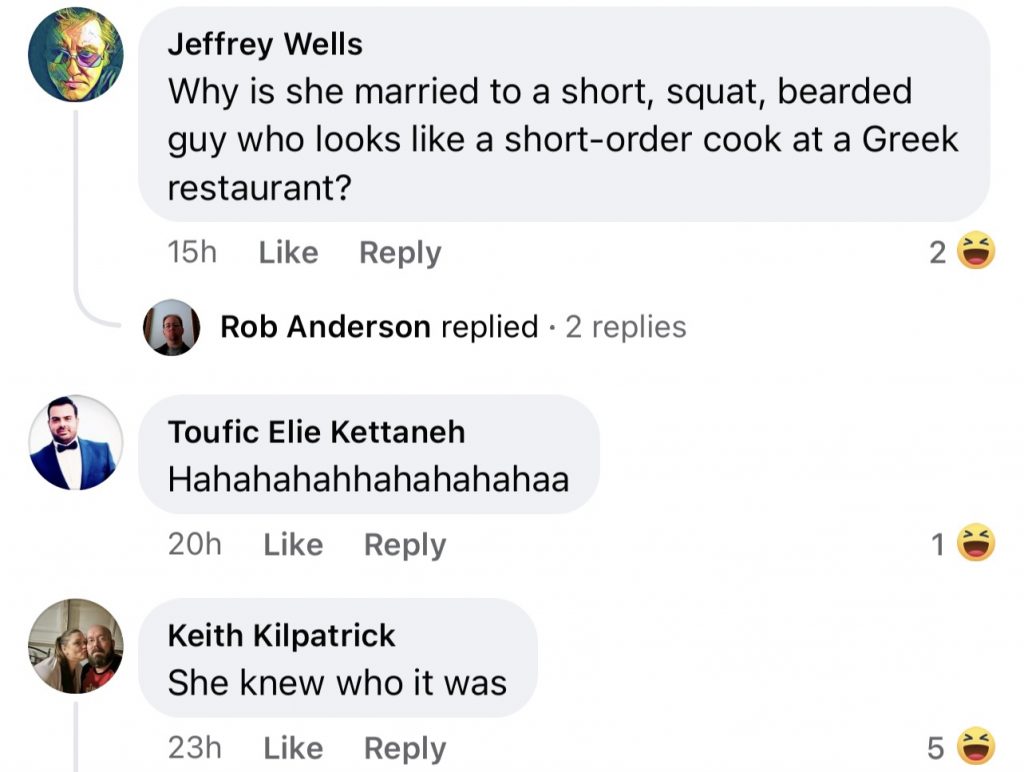

Tall sultry blonde foxes don’t get married to hobbits (i.e., Peter Jackson lookalikes) as a rule.

https://www.facebook.com/reel/890054525582016?fs=e&s=TIeQ9V&mibextid=0NULKw

Leaning on a recent Ipsos poll, a 3.8 USA Today article by Susan Page contends that “most” Americans — 56% — regard “woke” as a positive term, or a characterization of people who are aware of social inequities and attuned to social justice.

HE doesn’t believe this survey as it sharply argues with a 10.10.18 Atlantic article by Yascha Mounk that claims most Americans despise wokeness, which is almost invariably accompanied by notions of p.c. beratings and condemnations.

Last night the USA Today piece provoked a debate between myself and a journalist friendo.

Friendo: The Atlantic poll is over four years old. The USA Today poll is recent. Maybe things have changed.

HE: Bullshit. Average Americans loathe and despise the cancel culture crowd.

Friendo: Are you prepared to critique the methodology of the poll? If not, it’s just your opinion.

HE: The 56% in the USA Today Ipsos poll who regard the term favorably are defining it, somewhat Pollyanically, as attuned to social fairness, aware of inequities, focused on decency and justice, etc. In other words, they were misled or boondoggled by a dishonest definition provided by dishonest Ipsos pollsters. Wokeness is a cult religion focused on purist p.c. ideals, revolutionary social correction and punitive measures for those who aren’t sold on it. As Quentin Tarantino once wrote, “Sell that bullshit to the tourists.”

Friendo: The definition of woke is “alert to injustice and discrimination in society.” That seens to be what the pollsters [are running] with.

HE: That’s an evasive definition, to put it politely. In the realm of actual social reality it’s a lying bullshit definition, and the pollsters know that. And so do you.

Friendo: Straight out of the dictionary, my friend.

HE: The people behind the dictionary definition are sidestepping the truth of the matter. Another way of putting it is that they’re being willfully oblivious.

Friendo: A dictionary is apolitical. You want a political definition, go somewhere else.

HE: Beginning in the early 1950s, American anti-Communist activists were dedicated to protecting this country from internal subversion, and their efforts to keep Hollywood films free of this socialist influence were honorable and vigilant. If you want a political definition, search elsewhere.

Friendo #2: The USA Today poll was probably skewed more towards Democrats-leaning voters — that’s a demographic that would overwhelmingly be pro-woke. No surprise that the article states that almost 80% of Democrat respondents said they were pro-woke. I mean, are you surprised?