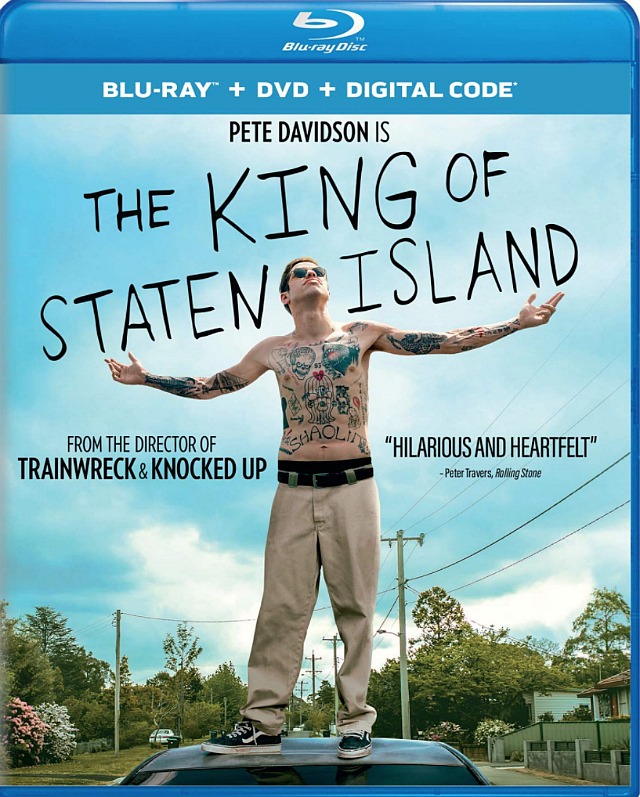

HE comment posted on 8.25.20, sometime around 6:30 am: “How telling that Jimmy Porter feels the urge to rub in the fact that The King of Staten Island didn’t fully connect with people who wanted and expected a semblance of the usual usual. KOSI reps an exotic realm in more ways than one, acknowledged, but it walks and talks in a completely honest and straightforward way. It has the courage to be funny on its own terms. You have to ‘let it in’ and accept Judd Apatow and Pete Davidson’s idea (revelation?) that Staten Island really is, from a certain perspective, this strange, half-forsaken, outback culture (part blue-collar, part stoner, in some ways hermetic) that even New Jerseyans look down upon. For a sizable sector (i.e., the Jimmy Porters of the world) KOSI was a zone apart and an attitude too far. I almost felt that way at first, but then it winnowed its way in.”

From “The Staten Island Funnies,” posted on 6.8.20: You know you’re in good hands when a film you’ve clicked with seems to be more on-point the second time. Last week I got an even better kick out of The King of Staten Island and enjoyed the performances all the more, not to mention the exotic atmosphere and how it all fits together in a reasonably neat and satisfying way. And without a single ounce of fat.

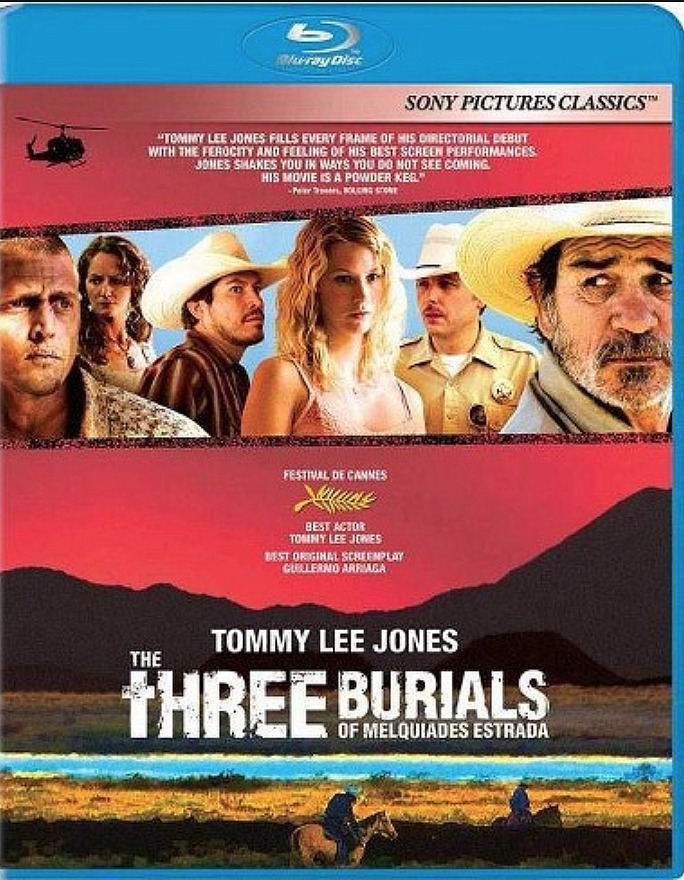

For my money The King of Staten Island is easily as good as Judd Apatow‘s Funny People (although a bit more despairing and downmarket) and at times as emotionally poignant as Trainwreck but braver, in a sense.

It’s significant that the film doesn’t hop on the ferry and visit lower Manhattan until the very last scene. Because the KOSI version of Staten Island is really a zone apart — thousands of miles from Brooklyn and Manhattan. Scott’s stoner bros (including “fat Kanye”) are so low-rent and devolved they pretty much border on the vegetative.

But I admired the commitment to this realm. The comedy hasn’t been sitcommed or punched up, or at least not in the usual ways. It feels real and grounded, and yet, per standard practice when it comes to Apatow’s brand, carefully honed and sculpted as far as the unrefined voices of the various characters are concerned. I loved that the film doesn’t feel slick or overly “presented”.