I’m on a Virgin America flight as we speak with a Los Angeles touchdown in three hours (i.e., around 4 pm). I’ll be returning to NYC for a quick visit later this month but otherwise no action until the 2016 Telluride, Toronto and New York film festivals. Nearly three months of staying put. A lot of movie-watching and meditation upon same, and the a.c. getting a good workout.

What does the summer slate look like? “Mostly dreadful” would be putting it mildly, but at least there’s Jason Bourne, the very well-reviewed Hell or High Water, John Lee Hancock‘s The Founder, David Ayer‘s Suicide Squad, Woody Allen‘s entirely decent Cafe Society, Richard Tanne‘s Southside With You and eight or nine others — 14 in all.

In order of release dates, the following have at least a semblance of insect antennae heat. Some seen, mostly unseen, all with a current of some kind:

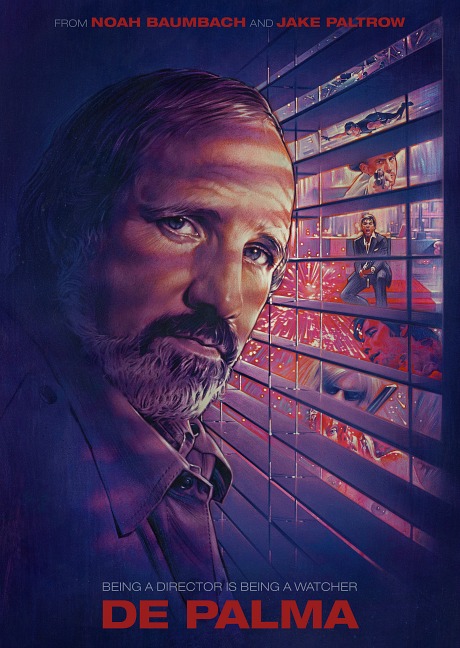

Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow‘s De Palma (A24, 6.10), which I’ll be seeing tonight at a 7 pm screening.

Benoit Jacquot‘s Diary of a Chambermaid (Cohen Media Group, 6.10) — 79% RT score out of the Berlin Film Festival.

Gary Ross‘s Free State of Jones (STX, 6.24). Expectations are not high but at the least the combat sequences appear to be well handled, to judge by the trailer.

Thorsten Schutte‘s Eat That Question: Frank Zappa in His Own Words (Sony Classics, 6.24).

Read more