I missed this morning’s screening of Ralph Fiennes‘ Coriolanus, but at the 1 pm Undefeated screening two seasoned critics raved about Vanessa Redgrave‘s performance as Volumnia, the mother of Fiennes’ titular character. Add Guy Lodge’s Berlin Film Festival rave and there doesn’t seem to be much doubt about Redgrave being a top contender for a Best Supporting Actress nomination.

Daily

Believe It Or Don't

My Week With Marilyn (Weinstein Co., 11.4) “belongs to Michelle Williams and she alone. That is all anyone will be talking about once people actually see the movie. There is absolutely, positively no doubt that Williams is right alongside Meryl Streep and Glenn Close at the very front of the Best Actress race.” — quote from smart, well-connected guy who’s seen it, quoted on 8.15.

I Don't Get It

Set in 1914 or thereabouts, David Cronenberg‘s A Dangerous Method (Sony Classics, 11.23) is about a kind of perverse relationship between the young Carl Jung (Michael Fassbender), his mentor Sigmund Freud (Viggo Mortensen), and Sabina Spielrein (Keira Knightley), a lady with “issues,” as we would say today. But if I didn’t know the background and was just strolling around a theatre lobby in an orange T-shirt and cutoffs with a pot belly and big tub of popcorn, I’d be presuming that Knightley is playing a ghost of some kind…right?

Gay Oppression

This “Funny or Die” video about Dave (brother of James) Franco effing himself is…what, mildly amusing? Less so? it’s also a little “enough already” given the cavalcade of gay-themed roles and films that James has made over the last couple of years (playing Scott Smith in Milk, Allen Ginsberg in Howl and Hart Crane in The Broken Tower plus having directed that Sal Mineo movie).

The Franco brothers aren’t exactly Olsen and Johnson or Laurel and Hardy, but they’ve made videos together and are known as having started in the same genetic dugout, and between the two of them there’s been a little too much man-meat. For the next four or five years they really need to give homosexual congress a rest. Make it nine or ten years. It’s jgetting too one-note….gay this, gay that, gay whatever.

Four NYFF Extras

Four highly cool New York Film Festival extras were announced this morning. The coolest, for me, will be a screening of the first three episodes of Oliver Stone‘s The Untold History of the United States, the forthcoming Showtime series. They segments will focus “on the events leading up to America’s entrance into World War II, the war itself, and the unjustly forgotten figure of former U.S. Vice President Henry Wallace,” says the release.

The Untold screening will be followed by a panel discussion featuring Stone, co-writer Peter Kuznick, historian Douglas Brinkley and The Nation‘s Jonathan Schell.

The second coolest will be a panel discussion of Pauline Kael by way of two books about the celebrated film critic — Brian Kellow‘s “Pauline Kael: A Life in the Dark” and “The Age of Movies: Selected Writings of Pauline Kael“. Panelists will include director James Toback (whose Fingers will screen after the discussion), New York critic David Edelstein, Kellow, Geoffrey O’Brien and University fo the Arts professor Camille Paglia.

The third-coolest, I suspect, will be Tahrir, a doc about the Egyptian uprising by Stefano Savona. (I wonder if the doc will be so caught up the thrill of revolution that it’ll choose to ignore the sexual mauling of CBS journalist Lara Logan, an incident that left a bad taste in everyone’s mouth, or get into it or what.)

And the fourth-coolest will be Jeffrey Schwartz‘s Vito, a doc about groundbreaking film critic and gay activist Vito Russo (The Celluloid Closet).

Set It Straight

Every year I say the same thing about the possible influence of MCN’s Gurus of Gold chart, and I might as well say it again with awards season about to kick off the weekend after next and with the first testing-the-waters Gurus of Gold chart having gone up yesterday.

Every year I ask what could be more worthless or contemptible in the eyes of any fim lover with the slightest trickle of blood in his or her veins than a group of online journos saying, “What we might personally think or feel about the year’s finest films is not our charge. We are here to read and evaluate the feelings and judgments of that crowd of people standing around in that other room….see them? Those older, nice-looking, well-dressed ones standing around and sipping wine and munching on tomato-and mozzarella bruschetta? Watching them is what we do. We sniff around, sense the mood, follow their lead, and totally pivot on their every word or derisive snort or burst of applause at Academy screenings.”

If I could clap my hands three times and banish the concept of Gurus of Gold from the minds of my online colleagues and competitors, I would clap my hands three times. For it is the task of Movie Catholics (which includes all monks and priests and followers of the faith) to stand up and lead at all costs. And it is bad personal karma to put aside what every fibre of your being tells you is the “right” thing to do in order to proclaim (and therefore help to semi-validate and cast a favorable light upon) the occasionally questionable sentiments and allegiances of others.

And I mean especially if these temperature-gauging, tea-leaf readings contribute to a snowball mentality or growing assumption that a certain Best Picture contender has the heat. There is no question in my mind that to some extent the Gurus of Gold (and especially the purely analytical temperature-takers like EW‘s Dave Karger) contributed to last year’s Best Picture win by The King’s Speech by advancing the notion each and every week that it would probably take it. And that, if you don’t mind me saying so, is a terrible thing to live with.

How would you feel if you were 92 years old, let’s say, and on your death bed and looking back upon your professional Hollywood life and saying to yourself, “In my own small but possibly significant way, I probably helped to create a perception of groundswell momentum and inevitability that led to the Best Picture triumphs of The Greatest Show on Earth, Around The World in Eighty Days and Driving Miss Daisy“? How would you feel about that? Good?

True Catholics are players on the field, not watchers from the stands. They need to convey their own passions as personally, ardently and persuasively as possible, and to give as little credence as possible to the alleged preferences of a politically-motivated, comfort-seeking, sentimentally-inclined, wowed-by-almost-anything-British and recently suspect industry group.

It’s been pointed out time and again that the Academy had a reasonable, fair-minded history in their Best Picture preferences from the mid aughts to ’10 but then last year did an about-face and, in a startling cave-in to British kowtowing and comforting gutty-wut sentiment, gave the Oscar to an admirable-but-far-from-good-enough contender. For the sake of the Academy’s reputation among the aloof and justifiably cynical younger crowd (i.e., the ones that the Academy hopes might be attracted by the hand of Oscar-show producer Brett Ratner) and for the sake of our souls, a capitulation of this sort must never happen again.

Guru Peek-Out

“Hollywood Elsewhere’s view is that nothing is so objectionable as ‘conventional industry wisdom,’ especially as reflected in Gurus of Gold charts and other tabulations in this vein. Unless, that is, conventional industry wisdom happens to be in synch with what we strongly feel and/or believe in. Hah!” — a quote from a Hollywood Elsewhere’s 2011/12 advertising pitch letter.

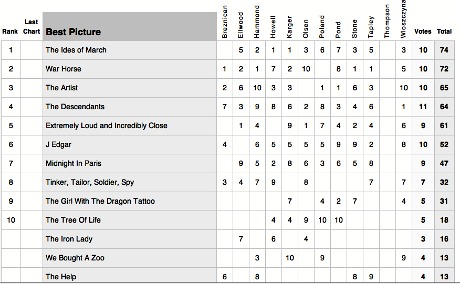

One noteworthy thing about the season’s first Guru chart are the indications of affection and prejudice toward certain films, a “1” vote idiotically being the highest and a “10” being the lowest. In what upside-down, hairy-kumquat realm does a lower number mean “better” and the lowest number is cause for celebration?

The Gurus with the most affection for Steven Spielberg‘s first-place The War Horse are EW‘s Anthony Breznican (1), Deadline‘s Pete Hammond (1), Sasha Stone (1) and Kris Tapley (1). David Poland, EW‘s Dave Karger and Hitfix‘s Gregg Ellwood each gave it a 2.

Spielberg’s less-engaged friends right now (and obviously this can and will change) are L.A. Times guy Mark Olsen (10), TheWrap‘s Steve Pond (8) and The Toronto Star‘s Pete Howell (7). What this means (and it means very little) is that some of these guys are feeling a certain cynical distance from The War Horse…that’s all. They’re probably a little tired of the emotional manipulations and John Williams scores that go into every other Spielberg film.

Another noteworthy thing about the season’s first Guru chart is that the Best Picture contender with the second highest vote tally is George Clooney‘s The Ides of March. Sight unseen, of course. Pure nothingness. All it means is that most of them want to see a smart political film with good acting and a strong theme about loyalty and betrayal, etc.

My top ten spitball contenders? In this order: Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, The Descendants, The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, The Ides of March, The Iron Lady, Moneyball, The War Horse, We Bought A Zoo, The Tree of LIfe and Midnight in Paris.

Son of "All RIght…Jesus!"

Yesterday I posted a podcast between myself, Jett Wells and Nathan Mattise on their weekly Whoa! magazine podcast. Mainly we discussed Telluride, Toronto, Drive, Andy Serkis and Warrior‘s Tom Hardy. And then it un-posted itself. Apparently there’s a gremlin in the system.

Positivism

Amy Winehouse‘s toxicology tests show that no illegal drugs were present in her body at the time of her death, the AP reports. She had booze in her system, but that’s generally not a fatal condition. A Winehouse family spokesman released a statement today saying that “toxicology results returned by authorities have confirmed that there were no illegal substances in Amy’s system at the time of her death.”

So what happened then? What 27 year-old just up and dies? What 27 year-old body says, “You know something? I’m getting really weary. I think it might be time to shut down. I’ve been trudging along on the hard road of life for 27 years, and it’s a real slog, lemme tell ya.”

Just then two other bodies — one 44 years old, another 52 years old and a third that’s 71 years old — come along and shake the 27 year-old body by the shoulders. “You’ve been on this earth for 27 years old and you’re thinking about shutting down and dying?,” the 52 year-old body says. “What’s wrong with you? We’re all doing fine and we’re not thinking of quitting so what the hell, homie? Nobody dies at 27 unless they’ve been influenced by a foreign substance.”

Knows No Bounds

The last time I looked the Civil Rights movement of the ’60s was about empowering the disenfranchised, particularly by ensuring that people of all ethnicities had the absolute right to vote. Today Gov. Rick Perry equated that struggle to the current efforts of right-wing, corporate-fellating serpents to lower taxes on business-owners and the corporate well-to-do. This, to him, is what American “freedom” is all about.

Original Design

No doubt about it: there were iPad-like devices in Stanley Kubrick‘s 2001: A Space Odyssey. They sure do look like iPads — same size, similar illumination, etc. Which doesn’t bode well for Apple’s attempt to prevent Samsung from selling its Galaxy Tab.

“Apple and Samsung are currently engaged in a high-stakes intellectual property battle, with Apple [looking] to stop Samsung from selling its Galaxy Tab and other Android-based products,” MacRumors reported this morning. “Apple claims that Samsung has infringed upon Apple’s intellectual property rights by copying the designs of popular Apple devices such as the iPhone and iPad.

“According to court filings, Samsung has presented a scene from Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey as evidence of prior art that should invalidate Apple’s design claims on the iPad.

“From the filing: ‘Attached hereto as Exhibit D is a true and correct copy of a still image taken from 2001: A Space Odyssey. In a clip from that film lasting about one minute, two astronauts are eating and at the same time using personal tablet computers. As with the design claimed by the D-889 Patent, the tablet disclosed in the clip has an overall rectangular shape with a dominant display screen, narrow borders, a predominately flat front surface, a flat back surface (which is evident because the tablets are lying flat on the table’s surface), and a thin form factor.

“‘The patent in question is a design patent covering the ornamental design of the iPad, with Apple claiming that the Samsung Galaxy Tab is substantially identical to that design.

“‘By pointing to an example of a similar design made public in 1968, even if not an actual functioning tablet device, Samsung hopes to demonstrate that there is little variation possible when designing a tablet and show that the general concept used by Apple for the iPad has actually been circulating for decades.'”

Lady In A House

Luc Besson‘s The Lady is a Toronto Film Festival-bound drama about the decade-long house arrest of the Burmese politician Aung San Suu Kyi (Michelle Yeoh), and also about her marriage to the late Dr. Michael Aris (David Thewlis). Honestly? The first three things that came to mind were as follows:

(a) A movie about a good woman being kept under house arrest for ten years?

(b) A movie about the not-exactly-Cary Grant-like Thewlis enjoying conjugal privleges with the beautiful Yeoh? Has Thewlis ever enjoyed nookie from any attractive woman in any movie, ever? Answer: Yes — Thandie Newton in Besieged.

(c) This, I’m betting, is a p.c. movie that’s about the audience feeling good about itself for watching a movie about a good, reform-minded woman being kept under house arrest for ten years.

“It is the fight of a woman without any weapons, just her kindness and her mentality. [Suu Kyi] is very Gandhi-like.” — Luc Besson.

The Lady script is by Rebecca Frayn “who began working on the project after she and her husband, producer Andy Harries, visited Burma in the early 1990s,” says the Wiki page. “Harries’ production company Left Bank Pictures began development of the script in 2008 under the working title Freedom from Fear. Harries wanted Michelle Yeoh as the lead and had the script sent to her.

“During the shooting of the film, news broke that Aung San Suu Kyi’s house arrest had been lifted and Yeoh was even allowed to visit her.

“Yeoh was deported from Burma on 6.22.11, reportedly over The Lady.”