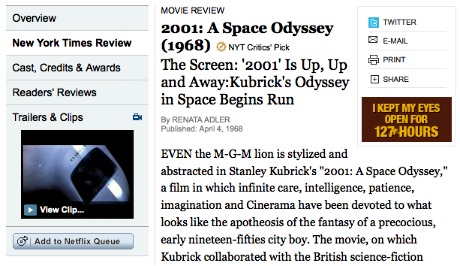

I’ve always loved Renata Adler‘s 4.4.68 review of 2001: A Space Odyssey. She didn’t really get it and in fact puts it down, but she’d gotten parts of it, or several fragments, and she knew (or sensed) there was probably more where that came from. She was only 30 when she wrote her piece, and probably had more than a few space-cadet friends who were getting high and listening to Dylan and the Beatles, etc. And a voice was telling her, “You’d be smart not to pan this outright despite your gut feelings…go a little easy.”

I’d like to think that if I’d seen one of the most unusual and challenging films of the ’60s cold and had to write a review right away, I’d have been as observant as she. I’d like to think I would have been a little more perceptive, but that’s easy to say.

“Even the M-G-M lion is stylized and abstracted in Stanley Kubrick‘s 2001: A Space Odyssey, a film in which infinite care, intelligence, patience, imagination and Cinerama have been devoted to what looks like the apotheosis of the fantasy of a precocious, early nineteen-fifties city boy.

“The movie, on which Kubrick collaborated with the British science-fiction author Arthur C. Clarke, is nominally about the finding, in the year 2001, of a camera-shy sentient slab on the moon and an expedition to the planet Jupiter to find whatever sentient being the slab is beaming its communications at.

“There is evidence in the film of Clarke’s belief that men’s minds will ultimately develop to the point where they dissolve in a kind of world mind. There is a subplot in the old science-fiction nightmare of man at terminal odds with his computer. There is one ultimate science-fiction voyage of a man (Keir Dullea) through outer and inner space, through the phases of his own life in time thrown out of phase by some higher intelligence, to his death and rebirth in what looked like an intergalactic embryo.

“But all this is the weakest side of a very complicated, languid movie — in which almost a half-hour passes before the first man appears and the first word is spoken, and an entire hour goes by before the plot even begins to declare itself. Its real energy seem to derive from that bespectacled prodigy reading comic books around the block.

“The whole sensibility is intellectual fifties child: chess games, bodybuilding exercises, beds on the spacecraft that look like camp bunks, other beds that look like Egyptian mummies, Richard Strauss music, time games, Strauss waltzes, Howard Johnson’s, birthday phone calls. In their space uniforms, the voyagers look like Jiminy Crickets. When they want to be let out of the craft they say, ‘Pod bay doors open,’ as one might say ‘Bomb bay doors open’ in every movie out of World War II.

“When the voyagers go off to plot against HAL, the computer, it might be HAL, the camper, they are ganging up on. When HAL is expiring, he sings ‘Daisy.’ Even the problem posed when identical twin computers, previously infallible, disagree is the kind of sentence-that-says-of-itself-I-lie paradox, which — along with the song and the nightmare of ganging up — belong to another age. When the final slab, a combination Prime Mover slab and coffin lid, closes in, it begins to resemble a fifties candy bar.

“The movie is so completely absorbed in its own problems, its use of color and space, its fanatical devotion to science-fiction detail, that it is somewhere between hypnotic and immensely boring. (With intermission, it is three hours long.) Kubrick seems as occupied with the best use of the outer edge of the screen as any painter, and he is particularly fond of simultaneous rotations, revolving, and straight forward motions — the visual equivalent of rubbing the stomach and patting the head.

“All kinds of minor touches are perfectly done: there are carnivorous apes that look real; when they throw their first bone weapon into the air, Kubrick cuts to a spacecraft; the amiable HAL begins most of his sentences with ‘Well,’ and his answer to ‘How’s everything?’ is, naturally, ‘Everything’s under control.’

“There is also a kind of fanaticism about other kinds of authenticity: space travelers look as sickly and exhausted as travelers usually do; they are exposed in space stations to depressing canned music; the viewer is often made to feel that the screen is the window of a spacecraft, and as Kubrick introduces one piece of unfamiliar apparatus after another — a craft that looks, from one angle, like a plumber’s helper with a fist on the end of it, a pod that resembles a limbed washing machine — the viewer is always made aware of exactly how it is used and where he is in it.

“The special effects in the movie — particularly a voyage, either through Dullea’s eye or through the slab and over the surface of Jupiter-Earth and into a period bedroom — are the best I have ever seen; and the number of ways in which the movie conveys visual information (there is very little dialogue) drives it to an outer limit of the visual.

“And yet the uncompromising slowness of the movie makes it hard to sit through without talking — and people on all sides when I saw it were talking almost throughout the film. Very annoying. With all its attention to detail — a kind of reveling in its own I.Q. — the movie acknowledged no obligation to validate its conclusion for those, me for example, who are not science-fiction buffs.

“By the end, three unreconciled plot lines — the slabs, Dullea’s aging, the period bedroom — are simply left there like a Rorschach, with murky implications of theology. This is a long step outside the convention, some extra scripts seem required, and the all-purpose answer, ‘relativity,’ does not really serve unless it can be verbalized.

“The movie opened yesterday at the Capitol.”