Welcome to the world of Valerie Van Galder, a 25-year veteran of big-studio publicity and marketing (a total hotshot in her day) and currently a mental health advocate. A resident of one of L.A.’s westside communities, Van Galder recently posted an audio-visual Facebook essay that caught my eye.

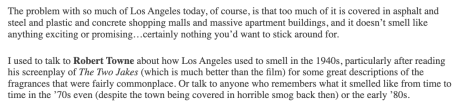

VVG basically said that while tourists see only the hotels, freeways, billboards, malls and gas stations, native Los Angelenos see some kind of mellow Garden of Gethsamene…a community built upon nourishing vibes and gentle fragrances, delicious ethnic food, winding two-lane blacktops in the hills, sea air and large swaying eucualyptus trees.

What she meant was that if you live in an affluent nabe and you make a concerted effort to mentally block out all the ugly stuff, Los Angeles can “seem” like a kind of heavenly, laid-back, coast-of-Italy Neverland, or at least something in the vein of Montecito or Mendocino or San Juan Capistrano.

Van Galder blocked and erased my reply so I can’t repeat it verbatim, but I basically said that L.A. can feel like a fairly nice place to hang if you keep to the flush zip codes (Beverly Hills & Bel Air, north of Montana, Brentwood, Pacific Palisades, Hollywood Hills, Hancock Park, Malibu hills, Trancas beaches, the various canyons, the walk streets of Venice) and tell yourself that the ugly aspects needn’t interfere with your spiritual head space, but the ugly, over-commercialized, heavily-congested, appalling and thoroughly blighted parts of town prevail above all.

Compared to so many European cities I could name, Los Angeles — not counting the above-named exceptions — is a sprawling, vaguely smelly, butt-ugly metropolis. Driving on Pacific Coast Highway alone is enough to trigger a tailspin depression.

L.A. was once was a moderately beautiful town…so much flora and nectar and sparkling clear vistas back in the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s…Robert Towne used to tell me all about it.

Here was Van Galder’s reply:

Posted on 12.5.24:

Posted on 10.17.06:

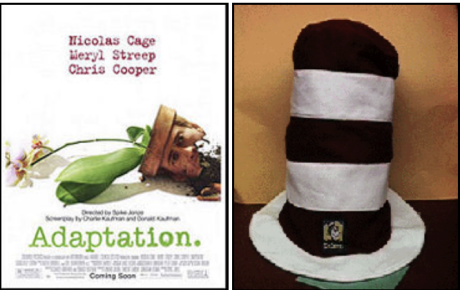

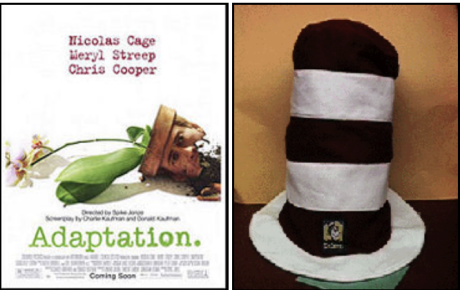

The Hollywood Reporter ran Nicole Sperling‘s nicely sculpted profile of Columbia TriStar marketing group president Valerie Van Galder yesterday…fine. I’ve always respected Van Galder’s aesthetic sense. I really admired that flower-pot concept in the Adaptation one-sheet that she worked on. I remember wanting to do an article on the various Adaptation poster concepts that she’d considered — she loved the film and was very enthused about getting the art just right — but the piece gradually died for some reason. Half me, half her.

I also remember Van Galder wearing one of those cat-in-the-hat hats in front of Park City’s Egyptian theatre in ’96 as I waited to scrounge a ticket for a public showing of Looking for Richard. Van Galder was a Fox Searchlight publicist and, let’s be honest, not exactly a friend. It was my choice to wait and hope — Valerie made no promises — but I stood in increasingly frigid cold for 45 minutes only to be told no-dice. It was nothing in the grand scheme and I naturally moved on, but on some residual level whenever I think of the talented and much-admired Val I think of the total absence of sensation in my toes that night, and the way snow was coming down so heavy and pretty, and how big Sundance kahuna Robert Redford and director-star Al Pacino drove up and jumped out of an SUV about ten minutes after the show was supposed to begin.

Posted on 10.15.06:

The sum effect of coverage of Marie-Antoinette in Vanity Fair, Vogue and the New Yorker along with the Kitson Boutique window treatments, wild posting and pink Converse sneakers…all of that…is “penetrating the culture,” Columbia marketing president Valerie Van Galder has told Hollywood Reporter columnist Anne Thompson.

“In just the way that Sofia didn’t treat [the story of Marie Antoinette] as a straight biopic, we’re taking a unique approach,” Van Galder explains. “We’re having fun with the marketing. The movie has captured people’s imagination.”

Surely Van Galder doesn’t mean the movie itself — which I’ve over-campaigned against, I realize — has done the capturing. What she means, I think, is that the idea of Sofia Coppola putting pink converse sneakers into a shot of Marie Antoinette’s closet (or against some other backdrop) has caught on within the culture of female movie journalists, columnists and magazine editors along with, I suppose, some of their male gay counterparts. Kind of a “you go, girl” thing.

Hollywood Bytes columnist Elizabeth Snead has written that “the modern pink footwear creates a funny, girly, rebellious moment in a frothy film about a young girl who just wants to flirt, shop and party in 18th century France. And the sneaks also work with the film’s punky pink ads and the pink-themed court parties, pink champagne, pink wigs, and pink pastries.

“More importantly, the shoes are also a bright pink emblem of Sofia’s creative and independent spirit.”

Snead reports in the same column that “someone asked Coppola about the pink tennis shoes and she explained that it was her brother Roman, her second assistant director on the film, who put them in the shot. Dunst stayed comfortable wearing pink Converse tennis shoes under her royal gowns during filming. You never see them on [her] but there is a funny shot of the tennis shoes that remains in the film.”