For most viewers, I suspect, Tony Gilroy‘s Duplicity will be talked about as a corporate mindgame confection — not a “thriller” per se (there’s only one sequence in which the tension is seriously cranked up) but a movie that is truly expert at delivering a series of dry little fake-outs and doing quick little leap-frogs over your expectations. I had a seriously pleasurable time watching it — don’t get me wrong. It’s an amazingly sharp and sophisticated and well-honed thing. As far this sort of adult international chess-game tends to play, it’s quite delicious.

The issue, for me and for potential viewers who have similar tastes and attention spans, is that the serious pleasure happened the second time I saw it. The first time? Not as much.

The problem, I confess, was more mine than Gilroy’s. I’m just not smart enough, you see, to get or enjoy all the twists and curve balls and keep the whole equation proportionately focused and sussed. Slow guy that I am, it was just too much work. Not all the time or even for much of the running time. I’m not a complete moron. But every so often I felt a bit burdened and blurry of mind. I felt overly fucked with, to put a point on it. “Wait a minute, is this…wait, is that what’s going on? I guess so, okay. But then why….?”

Unlike, I should add, my brilliant ex-wife Maggie, who had no trouble keeping up, and unlike the Einstein-level N.Y. Times critic A.O. Scott, who had the audacity to write in his review this morning that Duplicity “ends more or less as you always suspected it would.” (What?). A good mystery flick (or more precisely a good what-the-fuck-is-going-on? movie) is supposed to work on a dog-race principle. The audience is the dog pack and the stuff you’re trying to figure out is the artificial rabbit. The rabbit is always supposed to be just ahead of the dogs, but never so far ahead so that they lose hope and start to give up.

Put simply, my first Duplicity experience made me feel like the dumb dog sitting in the back row in math class in seventh grade. I haven’t felt that way in a long time. Because I was, in fact, that dumb kid, and it took me years to get past that image of myself as a guy who would never get good grades or go to a good college, who would never be very good at sports, who would never drive a slick car or get to disrobe those wonderfully busty blonde girls who always hung out with the jocks.

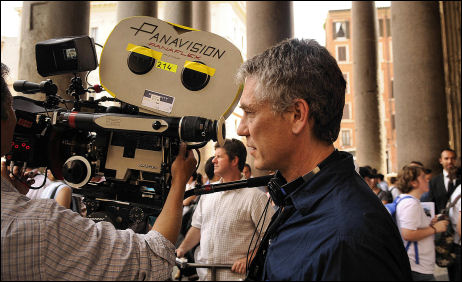

Duplicity director-write Tony Gilroy shooting next to Rome’s Pantheon

I was always good in high-school English and history and art class and gym (and smoking in the parking lot with my friends), but I despised math and chemistry. Most of the time I wanted to draw or look out the window. It was a miserable time in my life. So thank you, Tony Gilroy, for helping me to re-experience that sense of isolation and rage, that feeling of hell and futility.

I’ve since learned to be constructive with my comprehension problems. After my first encounter with Duplicity, I went back and read the script (which I had been too lazy to read all the way through when I was sent a copy last year) and talked it over with five or six critic friends, and all but one element (i.e., the scripted discussion between Clive Owen and Julia Roberts) began to come into focus. So the second time was cool. I liked it, I mean.

The undercurrent of Duplicity is about the difficulty of establishing genuine trust between lovers, and it was on this level that I connected with it the most fully. This can be a real-deal challenge in life, offering up one’s emotional underbelly, and it’s particularly well suited to a kind of love story (or lust story) in which a man and a woman who are very much alike and get what each other is about can’t quite let their guard down. Because each time they do, they run into an awful put-of-the-stomach feeling based on a suspicion that they’ve been played.

The tension in the Roberts-Owen relationship (if you want to read about the plot, read Scott’s review) is that the dialogue is magnificent, nimble and quick, and yet relaxed and convivial. But the basic vibe is cynical and guarded and defined by anxiety. The offshoot is that you, the movie-watcher, don’t really trust these two either, even when it appears that they’ve resolved matters. They’re a good-looking pair, but a long way from establishing that Trevor Howard and Wendy Hiller vibe in Brief Encounter.

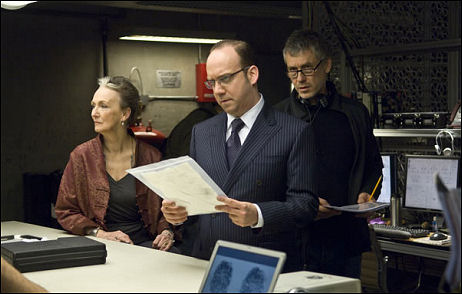

Paul Giamatti, Tony Gilroy

And with Roberts, as I’ve said before, I just don’t believe there’s a chance of any kind of peace with her. She’s not an actress as much as a presence and a personality who gets hired to be in movies. And deep down, I suspect, she’s only into herself, her security, her portfolio, her kids, her vacation hideaway, her private perimeter. She’s a fighter, a pistolero, an alley cat, a bullshit-buster, a Roger Friedman disser. She’s magnetic and fascinating, but I don’t think you want to ever fall in love with a woman like this. I’m not sure you’d even want to sleep with her. Even that might involve too much risk and melodrama.

You know what? Here comes a quasi-spoiler, which I feel is necessary to help the dummies out there.

The thing that everyone will talk about after seeing it is that Roberts-Owen have a particular conversation four times, each line repeated just so, line for line. There’s the original time plus three other times (including a rehearsal scene). because, this being a film about corporate espionage, they’re certain they’re being taped. What they say is immaterial; the repetition is all. Except it’s a pain in the ass.

Here comes the quasi-spoiler, which is based, I’ll admit, on a possibly flawed recollection. Ready?

The first time we see “the conversation,” in midtown Manhattan, they’re acting it because they know they’re being taped. The second time, in Rome, is the real thing: the two of them actually having this conversation for the first time after they reconnect for the first time since Dubai. The third time is when Duke (Dennis O’Hare) and another guy plays a recording of that Manhattan conversation that we saw in the beginning of the film. And the fourth time we hear it is in the wrapup, when they’re rehearsing the chat in Roberts’ New York apartment, unaware they’re being taped, rehearsing for the encounter that we first see near the beginning of the film. There — I’ve said enough.

More than anything else, I loved Paul Giamatti‘s feisty, highly-cranked CEO with an ego the size of a super-cruiser. When he’s on and in a half-decent film, the man is pure pleasure. So the price of your Duplicity ticket price is more than worth it for him alone.

But Gilroy, I think, got too caught up in his three-card monte game and keeping ahead of the people in the audience who are always trying to guess what will happen or where the plot will ultimately go . I’m not saying he outsmarted himself exactly, but he uncertainly outsmarted me. At least to the extent that Duplicity sometimes makes your brain feel like it’s being pulled in two or three directions, like turkish taffy. On top of which it’s…how to say it? Duplicity is not emotionally untrustworthy as it doesn’t really try for emotional trust in the first place by the act of casting Roberts, who, I believe, is first, last and always a misery-dispensing harridan.

I suspect it’s going to do well with the Maggie Wells and Tony Scotts of the world, but most of the public out there is, I suspect, on my intelligence level, which means that Duplicity may run into trouble starting with the second weekend. But I’m delighted that there are guys like Gilroy who write delightfully smart movies. It’s just that this time I loved the effort more than the execution.