The legendary Jane Goodall, the British primatologist and anthropologist commonly regarded as the world’s foremost expert on chimpanzees, has been interviewed and profiled countless times over the last 50-plus years. Everyone loves and admires her, and we all want to be as sharp, lucid and healthy as Goodall when we hit 83, which is where she is now.

Brett Morgen’s Jane (National Geographic, 10.20) is merely the latest filmed tribute to Goodall’s devotional calling, which began in Gombe, Tanzania in 1960 or ’62 or something like that, and continued into the 21st Century. The film covers her upbringing, how she got started at a chimp-watcher, her principal primate observations, anecdotes about her personal life, etc.

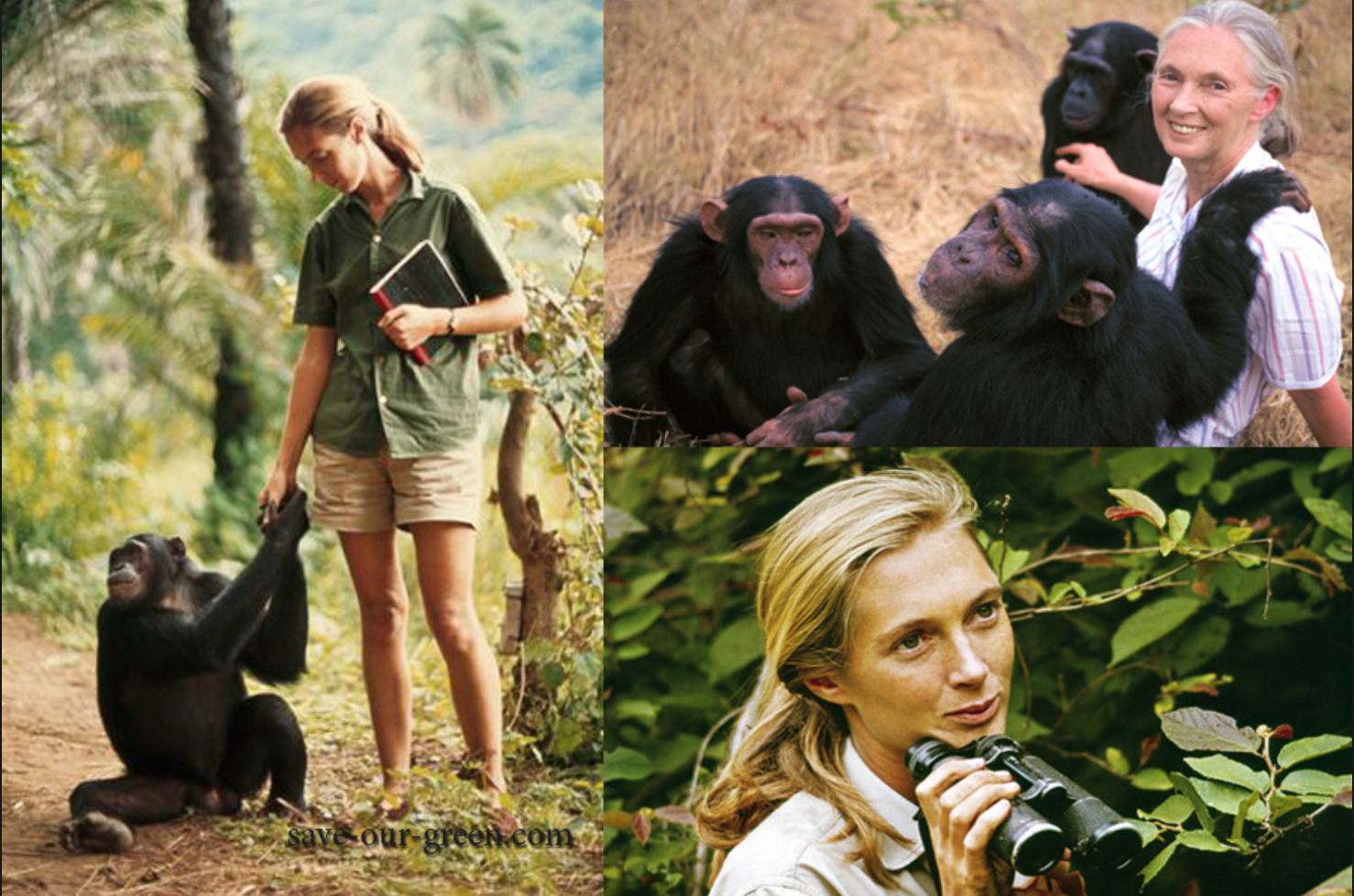

Does Morgen’s doc pass along anything new about Goodall? As far as I can discern, nope. It does, however, unspool a trove of heretofore-unseen 16mm color footage of of Goodall studying chimp behavior, shot during the ’60s and early ’70s by her then-husband Hugo van Lawick. The footage is luminous, well-framed and apparently was always shot around magic hour — Lawick had an eye, knew his craft.

On top of which Jane has been scored by Phillip Glass, whose symphonies always sound similar and I don’t care. (I know his Fog of War soundtrack backwards and forwards.) And it contains a lot of recent footage of Goodall talking to Morgen about pretty much everything.

Jane is a good and moving film. It has spirit, love…a glow about it. There have been many filmed studies of Goodall and her work, but this is the first smoothly composed, bucks-up, Hollywood-friendly version. Glass’s score encourages you to feel a bit of what Goodall probably felt or sensed as she began her studies. The film is comprehensive but not excessively so. It ignores a ton of material, but it only runs 90 minutes so whaddaya want?

I saw Jane last night at the Hollywood Bowl, at the invitation of National Geographic Films. Goodall and Morgen came out before the show began and shared a few words. Glass’s score was performed live as the film showed on a fairly large screen. The air was warmish, the sky was clear — a very soothing atmosphere. Will Jane be nominated for a Best Feature Documentary Oscar? Sure — why not?

Sidenote: A picnic bag of free food was provided to every invitee. The vittles included roast beef, watermelon and goat cheese salad, a sesame seed baguette, mixed berries and sweet cream, shrimp and a pint of shrimp sauce, a bottle of red and white wine, etc. I was concentrating on the shrimp and the shrimp sauce, and that was my undoing. At some point I shifted in my seat the wrong way and the open container of sauce flipped over and kerplopped on my lap. I moaned like a wildebeest being eaten by wild dogs. My right jeans leg was covered in red glop; both suede shoes, my socks and my black jacket got fuck-smeared also. “Ohhh, God…this is disgusting!” I went off to the bathroom and used about 75 paper towels to try and remove most of the shrimp sauce. It took me about 45 minutes to emotionally recover.

Did I let the shrimp-sauce disaster get in the way of my respect for Ms. Goodall or my admiration of her work or my enjoyment of Jane? Of course not. I’m not a six-year-old. On the other hand I’d be lying if I said I won’t think of that gloppy red goo every time I think of Goodall henceforth or consider a photo of a chimpanzee.

Here’s a 40 year old People magazine piece about Goodall and her second husband, Derek Bryceson. Written by Peter Kovler and Judy Lansing, and published on 10.24.77:

When animal behaviorist Jane Good-all joined a group in 1972 to lobby for the creation of a national park in Tanzania’s Gombe region, she was not looking forward to the assignment. “We were scared,” she recalls of their meeting with the Tanzanian parks director, “because we had been told that he was mean and unsympathetic.” Two years later Goodall and the “mean and unsympathetic” parks director, Derek Bryceson, had divorced their spouses and married each other.

A Royal Air Force veteran who helped Tanzania win its independence in 1964, Bryceson, 54, does not remember much of that first encounter with Goodall, now 43. “But I distinctly recall when Jane came to parliament later to show her film on the chimpanzees,” says Bryceson, who is a member of Tanzania’s National Assembly as well as parks director. “She made a very definite impression.”

Goodall’s myth-shattering work with chimps has had the same impact on the world scientific community. Born in London to a middle-class family, she was working as a secretary when she traveled to Kenya and persuaded famed paleontologist Louis Leakey to hire her as his assistant. He was then digging in east Africa’s Olduvai Gorge for evidence of early man. Fascinated by man’s Darwinian link to the apes, Goodall later set up her own camp to study primate behavior in Gombe on the shores of Lake Tanganyika. She earned a doctorate in ethology (the study of animal behavior) at Cambridge University in 1965.

What she discovered in the 1960s radically altered some widely accepted notions. She found that chimpanzees—contrary to popular opinion at the time—were highly intelligent and social creatures who used tools, formed close and enduring attachments and communicated through gestures, sounds and facial expressions. (In 1972 she made another discovery, she says rather remorsefully: “That chimpanzees can be cannibals.”)

In 1964 Goodall married Dutch photographer Hugo van Lawick, whose pictures of Jane and her chimpanzees appeared in The National Geographic and LIFE. They had a son, Hugo Jr., nicknamed Grub, and Jane relied on some of her observations about apes in raising him. “The chimpanzees have an extremely close bond between mother and child,” she explains. “The mother is constantly with the child, and I raised Grub this way. I never left him for a full day until he was 3 years old.” Today Grub—whose first sentence was “That big lion out there eat me”—is a self-assured 11-year-old.

Like Goodall, Bryceson was inexorably drawn to Africa. Shot down in his fighter plane over Egypt during World War II, he was told that he would never walk again. But after three years of struggle he managed to get around with the aid of a cane (which he still uses). “It was an act of great courage,” his wife says.

Bryceson earned a degree in agriculture at Cambridge in 1947 and went to Africa because he “wanted to farm, and the opportunities for that were in Tanganyika.” He subsequently played a key role in the evolution of the British mandate—along with the island of Zanzibar—into the Republic of Tanzania.

His main goal as a politician these days, he says, is to protect the ever-dwindling African bush from further encroachments by civilization—a shared concern that ignited their relationship, both Bryceson and Goodall acknowledge. By that time her marriage to van Lawick was disintegrating. “Hugo and I had drifted apart,” she says of their 1974 divorce. “But we still remain the closest of friends. We see each other often, and when I go to England I stay at his flat.” Grub lives with his mother and Bryceson but at present is at boarding school in England.

Bryceson’s 1974 divorce from his first wife was anything but amicable. His son, Ian, a 25-year-old marine biologist who teaches at the University of Dar es Salaam, has not spoken to his father since.

Like his son, Bryceson is interested in marine life. Whenever he and his wife are in Dar es Salaam, where they own an oceanfront home next door to Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere, they stroll the beach collecting specimens.

Much of their time, however, is spent doing field work in Gombe, visiting England or lecturing in the U.S. Goodall’s favorite theme is child-rearing, chimp-style. “People who don’t have time to raise their own children shouldn’t have them,” she declares. “Maybe the current ways like day care are correct. But I feel that leaving a baby for hours without its mother is bound to affect the way it relates to people. I preferred the chimp way, so I cuddled Grub lots.”

Not surprisingly, Goodall’s and Bryceson’s careers leave them with few evenings open for political or diplomatic socializing. “What we enjoy most is dining alone,” says Jane. “The ideal life,” Derek interjects wistfully, “would be to stay all year at Gombe, by the clear lake—far away from the city.”