34 degrees in Lone Pine — good morning. The snow-covered Sierra Nevadas loom in the near distance. The air is intoxicating but a bit thin, and obviously nippy. I’m looking around for a nice, well-heated breakfast diner as we speak.

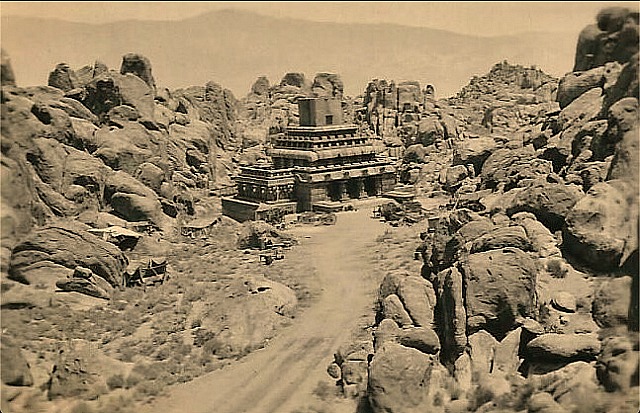

George Stevens‘ Gunga Din, which no self-respecting Millennial or GenZ-er gives a shit about, shot its outdoor footage in the Alabama Hills region, about 35 or 40 minutes away. Above-the-title talent (Stevens, Victor McLaglen, Cary Grant, Sam Jaffe, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., Eduardo Cianelli, Joan Fontaine) stayed in the original Dow Villa, which was built in the early 1920s. But production company grunts and extras slept in a tent camp and used temporary showers and latrines. I don’t know how long the Lone Pine shoot lasted, but the whole film took just shy of four months — 6.24.38 to 10.19.38.

Gunga Din opened on 2.17.39, when the late William Goldman, who wrote so passionately about Jaffe’s “stupid courage” during the Khyber Pass action finale, was but a lad of seven. It grossed $2,807,000 and ranked #10 on the top-grossing films of 1939, but it cost $1,915,000 to complete and therefore, by RKO Radio Pictures bookkeeping standards, recorded a loss of $193K.

A Hollywood Elsewhere Gunga Din riff that I posted on 12.24.17.

Here’s a piece about Eduardo Cianelli‘s “guru” character, posted four years ago (2.22.15) and titled “Among Filmdom’s Wisest and Most Elegant Villains“:

“In the legendary Gunga Din, Eduardo Ciannelli‘s fanatical leader of the Thug rebellion is called a ‘tormenting fiend’ by Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. and is made to seem demonic in that famously lighted shot by dp Joseph H. August. But he’s easily the most principled, eloquent and courageous man in the film. Not to mention the most highly educated.

“And yet there’s an unlikely scene inside the temple that hinges on Ciannelli’s guru being unable to read English, despite his Oxford don bearing and his vast knowledge of world history.

“Otis Ferguson‘s review of this 1939 adventure flick called it a racist and arrogant celebration of British colonial rule. And yet I’ve been emotionally touched and roused by this film all my life. The last half-hour of Gunga Din is perfect, but it ends with Sam Jaffe‘s Indian ‘bhisti’ basking in post-mortem nirvana over having been accepted as a British soldier.

“Which raises a question: Which films have you admired or even loved despite knowing they stand for the wrong things and/or tell appalling lies about the way things are or used to be?”