I thought I’d post this back-and-forth between myself and Bob Furmanek, which happened yesterday morning (or Monday, 1.28). It shows the difference between the mentality of a neutral-attitude, data-chip statistician vs. that of an emotional film lover like myself. Never the twain shall meet.

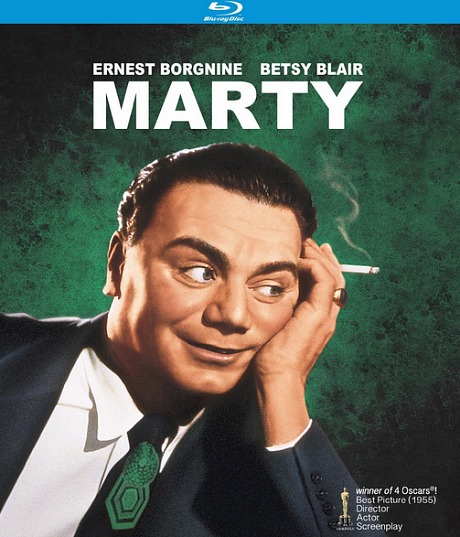

It’s interesting because Furmanek has been a noted provider of meticulous research that has convinced certain Bluray distributors to present 1950s-era films within a 1.85-to-1 aspect ratio because this is how films were generally projected starting in mid 1953. The point of contention was a 1.27 HE story called “Historical Precedent,” which concerned the forthcoming Criterion Bluray of On The Waterfront.

Furmanek: In case you’re wondering, On The Waterfront was originally presented theatrically in 1.85:1.

Wells to Furmanek: I’m not wondering about this because it’s common knowledge, thanks to your research. I stated in the piece that OTW was shot with the understanding that it would be shown at 1.85 in urban theatres. Under duress, of course, but Kazan did frame each scene so it would look good within a 1.85 to 1 aspect ratio. But Kazan also composed for TV. Because he knew his film would be shown on the tube down the road, and because he was used to shooting boxy going back to A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. Remember that WOR TV’s Million Dollar Movie began airing in 1955, or a year after OTW opened. The writing was on the wall.

Back to Furmanek: However, Grover Crisp‘s recommended ratio is 1.66:1. His credentials are exemplary and I respect his opinion.

Wells to Furmanek: Good for Grover, but what do you think, Bob? What do you want? How do you feel? You call yourself a neutralist and a stats man, but do you have a secret yen to see everything cleavered down to 1.85? You say you’re not on a campaign to see naturally boxy (1.33) or at least somewhat spacious 1950s and early ’60s compositions compressed into a 1.85 to 1 space? Who cares what exhibitors and distributors wanted to see in 1954 in order to make films of the day look cooler than television? Who gives a shit? Why should that be a factor in how we see films of the ’50s and early ’60s today?

Are you a boxy-is-beautiful type of guy (like me) or at least a 1.66-is-better-than-1.85 type of guy or what? Or are you strictly a neutral-minded research guy without any aesthetic preference? Because you never explain what you like and why. You never express who you really are.

You’re a very mellow, meticulous and well-mannered guy, Bob, but you seem to be comme ci comme ca about cleavering the tops and bottoms of iconic images, and for the life of me I don’t see why anyone who ostensibly cares about motion pictures would want images chopped down or otherwise reduced.

I am a boxy-is-beautiful guy, and if not that at least a 1.66-is-better-than-1.85 guy, and I’m extremely proud of being that. I say eff what the exhibitors and distributors wanted in 1954. Eff their priorities and their fears and their mid ’50s thinking. I am here now in 2012 and I like fucking breathing room or headroom, and if it’s viewable on the negative I said open it up and let God’s light and space into the frame. I really don’t like that horrible Being John Malkovich feeling of the ceiling pressing down upon actors, of walking around in a bent-over position like Orson Bean and his employees in order to exist within a 1.85 realm. I hate, hate, hate 1.85 fascism. Stop being a stats man, Furmanek, and let your real self out of the box. Who are you? What are you? What kind of a visual realm do you want to live in?

Back to Furmanek: Columbia — as a matter of studio policy — never utilized or recommended 1.66:1 as a presentation ratio. Beginning with principal photography of Miss Sadie Thompson on March 31, 1953, they were 1.85:1 for all non-anamorphic widescreen films.

If you are looking to experience the film as it was seen in first-run theaters around the country, including the world premiere at New York’s Astor Theater on July 28.1954, I would go with 1.85:1. The Astor had re-opened with a new panoramic screen on June 30, 1953.

In the UK, it was probably seen in most major theaters in 1.65:1 which was their widescreen standard at that time of release.

For the record, I have never endorsed an overall non-anamorphic widescreen standard of 1.85:1. I have always recommended honoring the ratio intended by the director and DP which would have been dictated by studio policy at the time of production. That can vary anywhere from 1.65:1 to 2.00:1.

Paramount was the first studio to officially adopt 1.66:1 as their house ratio on March 24, 1953. The only other studios to utilize that ratio domestically were RKO and Republic, both converting to widescreen cinematography in May of 1953.

Paramount retained 1.66:1 as their house ratio until September 21, 1953 when White Christmas began filming in VistaVision and was recommended for 1.85:1.

Sabrina is the odd AR title in Paramount’s output at that time. Wilder initially announced 2.00:1 but settled on 1.75:1 as his preferred ratio when production commenced in New York on September 28, 1953.

In the UK, the initial widescreen ratio was 1.65:1. That remained in effect from June 1953 until late 1954 when it changed to 1.66:1. At that time, the Cinema Exhibitors Association recommended the UK standardization of 1.75:1 which would remain in effect throughout the 1960’s. Documents can be found on this page: http://www.hometheaterforum.com/t/319469/aspect-ratio-research/1140#post_3989270

Every studio had their own policy. For information on Warner Bros, check out http://www.3dfilmarchive.com/dial-m-blu-ray-review

Information on Universal-International can be found here: http://www.3dfilmarchive.com/an-in-depth-look-at-creature-from-the-black-lagoon-1

You might like to know that shorts, cartoons and newsreels were also changed to widescreen composition in 1953: http://www.hometheaterforum.com/t/319469/aspect-ratio-research/720#post_3974959

I hope this answers your questions. If not, please contact me through the website and I’ll be glad to help in any way that I can.

Best,

Bob Furmanek

www.3dfilmarchive.com