South of the W hotel after a Los Angeles Film Festival screening — 6.20, 10:45 pm

In his latest essay Reid Rosefelt recalls his publicity association with legendary director Andrei Tarkovsky, the great Russian director who had less than 54 years on the planet.

Myron and Geoff Bresnick of Grange Communications “took Tarkovsky to the Telluride Festival, where they put on a big tribute for him in the Opera House,” he writes. “As soon as we got there, the festival directors Bill Pence and Tom Luddy whisked him away to points unknown. See ya! I thought that was a bit extreme as the Bresnicks had gone to the great expense and hassle of bringing him to the U.S., as well as to Telluride.

“The idea of Telluride at that time was that publicity was strictly verboten, and publicists like me, while not completely persona non grata, weren’t supposed to work while they were there. Telluride opened up that policy years ago, but then it took a major effort just to locate Tarkovsky and meet my commitment for one measly phone interview. But the thing that really drove me nuts about the whole Telluride experience is that they programmed Ivan’s Childhood, the one Tarkovsky film I hadn’t seen, at the same time as the Tarkovsky tribute!

“But the tribute was amazing, as all Telluride tributes are. And after the festival ended, Geoff drove me back to Denver at what seemed like 150 mph the whole way, which now that I think of it is a perfect way to top off watching a lot of Tarkovsky films.”

It would appear that Tim Burton‘s Alice in Wonderland is rooted in the mid 19th Century (i.e., 1865) , when Lewis Carroll published the original book. (Which was followed by an 1871 sequel, “Through The Looking Glass.”) Hence the all-Anglo cast and lack of minorities, not to mention the possible absence of any political points or metaphors as they might apply to the present. But I don’t have the script.

For any half-literate person who’s ever turned on, Alice in Wonderland isn’t just a surrealist political satire but the ultimate hallucinogenic fantasy. For boomers and older GenXers it’s always been stoner central, Owsley/Sandoz ground zero, “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” in 19th Century garb, a Grace Slick anthem, etc. All of which is anathema, of course, to Disney and their antiseptic family demo. “Mommy, did grandma or grandpa ever eat mushrooms?”

Obviously not pictured above are Michael Sheen (the White Rabbit), Alan Rickman (the Caterpillar), Christopher Lee (the Jabberwock), Stephen Fry (the Cheshire Cat), Crispin Glover (the Knave of Hearts), Timothy Spall (the Bloodhound), etc.

It is little remembered that Cary Grant played the Mock Turtle in Norman Z. McLeod‘s 1933 version, or that Cary Cooper played the White Knight.

Chalk this up to Live Free & Die Hard or not, but either way action movies are being pressured into PG-13 ratings. Sylvester Stallone‘s comically porno-violent Rambo might have grossed more domestically with that rating. One difference between R and PG-13, I feel, should be a tone of obvious over-the-top absurdism. Because Rambo was clearly trying for a certain type of ridiculous-gore humor, it should have been handed a PG-13, exploding heads and all. R ratings should go to the violent films that really and truly mean it.

In a 6.21 review of the Dr. Strangelove Bluray, N.Y. Times DVD columnist Dave Kehr says that director Stanley Kubrick “had no discernible sense of humor.” Well, that’s bullshit but let’s first examine Kehr’s examples of Kubrick’s tone-deaf funny bone.

Peter Sellers‘ Strangelove and Sterling Hayden‘s Gen. Jack D. Ripper , he says, “seem less funny as their audacity has drained away.” Then he says that lines like ‘Gentlemen, you can’t fight in here! This is the War Room!’ “now seem more labored than deliciously droll.” And then he says that “the film may be at its best in those low-key moments when Sellers, playing the American president Merkin Muffley, chats nervously on the hot line with the unseen Soviet premier — moments that owe everything to Bob Newhart‘s classic telephone routines.”

Kubrick most definitely had a sense of humor. It happened to be on the dry and perverse side, and for the most part seemed aimed at people on the set who were on his wavelength. Kehr misleads in his piece by not acknowledging that the above-quoted lines are pretty much the only ones in the film that apppeared to be aimed at mainstream ticket buyers circa 1963, and which consequently have a dated, on-the-nose feel. They were thrown in, in other words, as concessions to then-popular taste in humor, which Kubrick was probably wise to do because most people — let’s face it — respond to obvious material that any twelve year-old would laugh at. Like Newhart’s phone bits.

Most of the Strangelove humor is aimed, it has always seemed to me, at educated types who’ve been around the block. It is subtle and slightly kinky, and always in an undersold vein . Here, I submit, is the funniest exchange in the whole film, and there’s not a “laugh line” to be found in any of it:

General Jack D. Ripper: You know when fluoridation first began?

Group Capt. Lionel Mandrake: I…no, no. I don’t, Jack.

Ripper: Nineteen hundred and forty-six. Nineteen forty-six, Mandrake. How does that coincide with your post-war Commie conspiracy, huh? It’s incredibly obvious, isn’t it? A foreign substance is introduced into our precious bodily fluids without the knowledge of the individual. Certainly without any choice. That’s the way your hard-core commie works.

Mandrake: Uh, Jack, Jack, listen, tell me, tell me, Jack. When did you first… become… well, develop this theory?

Ripper: Well, I, uh…I… I, uh… first became aware of it, Mandrake, during the physical act of love.

Mandrake: Oh! [doing what he can not to sound stunned]

Ripper: Yes, uhm…a profound sense of fatigue… a feeling of emptiness followed. Luckily I, uh… I was able to interpret these feelings correctly. Loss of essence.

Mandrake: Hmm.

Ripper: I can assure you it has not recurred, Mandrake. Women uh… women sense my power and they seek the life essence. I… I do not avoid women, Mandrake.

Mandrake: No.

Ripper: But I do deny them my essence.

The way Sellers quickly mutters a supportive “no” when Hayden says he doesn’t avoid women is a great improv — a touch of supportive osequiousness. It also reflects the film’s basic comic attitude, which constantly alludes to male sex drives and feelings of adequacy and inadequacy, etc. Another great bit is when Sellers almost asks Hayden when and how he cooked up his nutball theory but decides at the last second to ask when he first “developed” it, as if Hayden might have been working on a “purity of essence” essay with a team at the Rand Corporation.

Variety‘s Michael Fleming and Peter Bart don’t exactly say in so many words why Sony chief Amy Pascal put Steven Soderbergh‘s Moneyball, a fact-based sports biopic movie starring Brad Pitt, into limited turnaround last Friday, or 96 hours before it was supposed to begin filming on Monday (i.e., tomorrow).

But it seems as if (a) Pascal had it her head that Moneyball would be some kind of commercial hotpants Brad Pitt baseball movie and (b) what she realized she would be getting, after reading a final draft of Soderbergh and Steven Zallian‘s script last week, would be — surprise! — a cerebral, non-jockstrappy “Steven Soderbergh movie” with a sprinkling of Warren Beatty‘s Reds that she didn’t want to spend over $50 million on.

“Soderbergh and Pitt’s CAA reps spent the weekend attempting to get another studio to play ball in a game that will play out until Monday,” Fleming and Bart write. “If a new financier doesn’t emerge by tomorrow, Columbia will re-examine options that include replacing Soderbergh (and hoping that Pitt doesn’t ankle), delaying the film until she and the filmmaker find themselves in synch on the script, or pulling the plug.

“Even in the climate of heightened studio caution, the turnaround news on Moneyball is surprising, given that had reached the equivalent of third base. The picture was just 96 hours before the participants were ready to take the field, following three months of prep and with camera tests completed and cast and budget in place.

“Pascal’s wariness is hardly unfathomable, even though the script was approved by Major League Baseball. The film doesn’t follow the traditional narrative structure of most sports yarns. Moneyball is based on the bestselling Michael Lewis book about Billy Beane (Pitt), the former phenom who undermined his playing career by taking a big paycheck before he was ready, [but] who later resurfaced as the Oakland A’s general manager who found success fielding competitive teams for low cost, compared to the payrolls of league rivals like the New York Yankees.

“Aside from actors like Pitt and Demetri Martin, Soderbergh is using real ballplayers — like former A’s Scott Hatteberg and David Justice — as actors, he has also shot interviews with ballplayers like Beane’s former Mets teammates Lenny Dykstra, Mookie Wilson and Daryl Strawberry. Those vignettes are interspersed in the film in a style comparable to director Warren Beatty’s used of ‘witnesses’ in his celebrated film Reds.

“While Soderbergh is confident his take will work visually, Columbia brass had doubts on a film that costs north of $50 million. That is reasonable for a studio-funded pic that includes the discounted salary of a global star like Pitt, but baseball films traditionally don’t fare well on the global playing field.

“Columbia’s move to jettison a Pitt pic is ironic. Pitt dropped out of State of Playjust before that picture was to begin production, when he read the studio-approved shooting script that veered too far from the draft that prompted him to sign on. It is unusual to see a studio step off a film to which a superstar like Pitt is firmly committed.”

What this seems to mean is either that (a) Pascal doesn’t believe that stars like Pitt mean all that much when it comes to opening a costly film — that the movie itself has to have the commercial goods or it’s not worth doing, or that (b) she’s half-persuaded that the 46 year-old Pitt — 50 in four and a half years! — isn’t much of a star any more. Or a combination of both.

Pascal is too smart to have been under any illusion that she would be getting anything other than a “Steven Soderbergh film” — smart, probing, not a dumbassed date flick — out of Moneyball. It was never going to be Ocean’s 11 in cleats or Bull Durham or anything in that vein. So what exactly was so different and (to Pascal) freaky about the latest draft? I’ve got an earlier draft — someone please send along the new one so I can figure this out.

That May 4th letter from Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen director Michael Bay to Paramount honchos that TMZ posted earlier today is instructive because it tells you that Bay isn’t all that highly educated, or at least didn’t pay attention during English composition class in high school.

Content-wise it shows that he was angry that the Transformers sequel (out 6.24) wasn’t getting decent buzz. Maybe it wasn’t at the time and “no big deal” anyway — we all get angry and complain, etc. But the seventh-grade spellings and thoughtless, sloppy-ass sentence construction speak volumes.

But I like one portion of the letter because it shows that Bay understands pop-culture currents, that he doesn’t want to repeat mistakes, that he listens to Jerry Bruckheimer and can read the writing on the wall: “You all say it doesn’t matter,” he writes. “Everything matters! The first time any studio said this very thing to me was on The Island.

“Over the years Jerry Bruckheimer mentored me on event movies, [and] he had a mantra. ‘A studio that does not make it into an event [or] will it into an event [and] thinks the audience will just show up will always be bitten in the ass.” I love this line also: “Clips don’t blow people away!”

I fully understand and support what’s going on right now in the streets of Tehran because I’ve understood (and, let’s face it, practiced) rebellion all my life. But my understanding of the Islamic fundamentalist practice of stoning women as punishment for adultery and other crimes against Allah is a little different. I realize, of course, that this ghastly and horrific tradition is still practiced in certain Islamic backwaters, but it’s so beyond-the-pale in terms of cruelty and fiendish chauvinism that it doesn’t seem real. A part of me says, “C’mon, no…this is too much.”

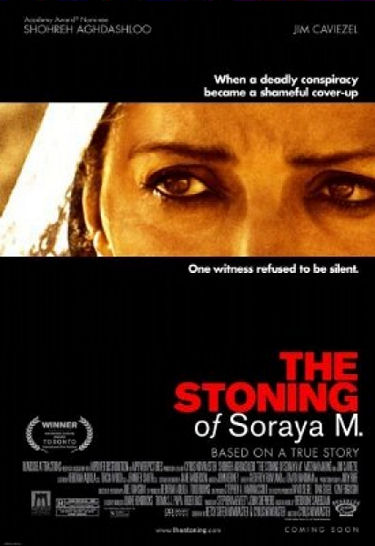

Which is why I couldn’t find my way into The Stoning of Soraya M., a respectably crafted, stirringly performed melodrama, based on Freidoune Sahebjam‘s 1995 book of the same name, about a stoning of a blameless woman in a small Iranian village in the mid 1980s.

I know that this ghastly murder occured (due to a conniving husband who wanted his wife out of the way so he could marry a younger woman) but as I watched it unfold I was saying to myself, “This happened on the planet Earth? Certain human beings of an Islamic stripe actually do this to women from time to time?” It felt beyond cold, beyond malignant.

The Stoning of Soraya M. makes Eli Roth‘s woman-hating Hostel 2 almost feel like humanism because at least (if you buy what Roth says) his film is an exercise in B-movie manipulation and therefore not rooted in anything “real,” and on top of this is at least familiar and recognizable in a cultural popcorn sense. Not so with Soraya M., which seems to be taking place on Mars.

At no point was I saying to myself “this isn’t a well-made film” or “this doesn’t cut it” or anything along those lines. The Stoning of Soraya M. is a reasonably solid B-plus docudrama, and anyone looking to work up a righteous head of steam about Islamic fundamentalism having unleashed cruel and backward and horribly chauvinistic cultural forces will find satisfaction.

My revulsion at what I saw in the film makes me an honorary right-winger, I think. I certainly feel like a rightie when I think about Islamic dictatorships and those effin’ mullahs. Count on it — Soraya M. will be popular among Jon Voight conservatives as well as the rich Iranians who fled their country after the 1979 Islamic revolution.

But I also knew I was watching a depiction of human behavior so far afield from anything I’d ever seen or imagined inside a movie theatre that I didn’t know what to do with it.

This despite a decision by director Cyrus Nowrasteh to portray Sahebjam’s tale in straight, plain terms, and the screenplay he wrote with wife Betsy Giffen Nowrasteh being matter-of-fact. Mozhan Marno is heartbreaking as Soraya — a feisty and spirited mother whose only error is not realizing soon enough that she’s doomed. Shoreh Agdashloo (House of Sand and Fog) delivers a powerhouse, potentially award-calibre performance as an older woman of authority who becomes Soraya’s only defender.

I’m not saying that the male Iranian villagers who conspired in the death of Soraya M. some 23 years ago showed any humanity or common decency, but the utter lack of such values among all but two male characters in the film presents a problem. There’s not a human being among them. Even the women act like fiends, or at least like acquiescent fools. It’s a ugly portrait of what humans are capable of, let me tell you.

The two exceptions are the village’s morally conflicted mayor, played by David Diaan, and a travelling journalist — a stand-in for Sahebjam played by Jim Caviezel — who is told about the stoning by Agdashloo’s character at the beginning of the film, and who leaves the village at the finale with an audio tape of her story.

Even if you share my confused reaction, there’s no arguing that Soraya M.‘s finale — a drawn-out depiction of Soraya’s brutal and bloody death — is devastating to sit through. When asked about the explicitness of this scene, Nowrasteh said that he’s a seen a tape of an actual stoning that was “much worse than what I’ve shown in the film” in terms being difficult to watch.

I saw The Stoning of Soraya M. yesterday afternoon at a Los Angeles Film Festival showing. The film will opens on Friday, 6.26. The post-screening panel included Nowrasteh, star Shoreh Agdashloo, religious scholar Reza Aslan and The Kite Runner author Khaled Hosseini, who moderated.

The title of this article, by the way, isn’t a quote from Soraya M. but The Verdict. It’s a line that Lindsay Crouse says on the witness stand in the big third-act testimony scene — “Who are these men? Who are these men? I wanted to be a nurse!” But it obviously fits.

Two videos from yesterday afternoon’s Los Angeles Film Festival showing of Cyrus Nowrasteh‘s The Stoning of Soraya M., which opens on Friday, 6.26. The post-screening panel included (l. to r.) Nowrasteh, star Shoreh Agdashloo, religious scholar Reza Aslan and The Kite Runner author Khaled Hosseini, who moderated.

The Proposal‘s estimated Friday gross of $12.4 million represents Sandra Bullock‘s biggest opening-day haul ever — fine. But what’s happened to poor Pelham? Tony Scott‘s subway thriller dropped over 60% compared to last Friday’s opening. You can’t even speak of Year One in the same breath as Pelham, and yet Harold Ramis‘s comedy earned $8.5 million yesterday. Shit floats.

“The chants of death to Khamenei are true,” a Canadian citizen has told Huffington Post live-logger Nico Pitney. “I witnessed people’s fear of the Basij disappear. I saw an 80 year old Chadori woman with rocks in her hands call for the execution of Khamenei and all Basij. A group of Basij were surrounded and forced into a building, [and then] the front was blocked with garbage and set on fire. The Basij opened fire on the crowd with what I assume were blanks. The crowd dispersed for a moment and then came back with a fury. That’s when the Molotov cocktails came out. When I moved on the building was on fire. An hour later when I passed by again there wasn’t much of a building left. There was full-blown war.”

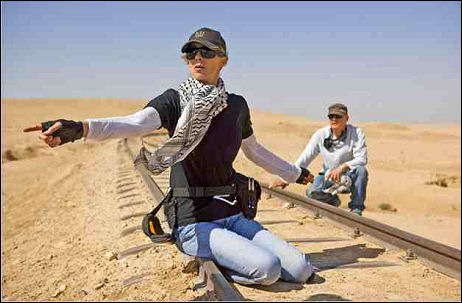

In a highly unusual and highly admiring interview piece, thorny N.Y. Times critic Manohla Dargis speaks with Hurt Locker director Kathryn Bigelow in tomorrow’s edition (i.e., Sunday). Are the Times editors telling Manohla to step outside the critics’ box and write more to beef up page views, or did she ask to interview Bigelow out of personal passion? Perhaps a little of both.

Bigelow’s film, says Dargis, was “greeted with rapturous praise and some misapprehension” after its Venice Film Festival premiere nine months ago. “Mostly, it seems, because its extraordinary filmmaking, which transmits the sickening addiction to war as well as its horrors in largely formal terms, doesn’t come wedded to a sufficiently obvious antiwar position. One British critic went so far as to say that while the film had ‘excellent acting, camerawork and editing, it could pass for propaganda.’

Except The Hurt Locker “doesn’t traffic in the armchair militarism of Hollywood products like Top Gun and Transformers,” she says, “[and] neither is it an antiwar screed. It’s diagnostic, not prescriptive: it takes an analytical if visceral look at how the experience of war can change a man, how it eats into his brain so badly he ends up hooked on it.

“And, like all seven of Ms. Bigelow’s previous feature films, this new one is also as informed by the radical aspirations of conceptual art as it is by the techniques of classical Hollywood cinema.”