“About two years ago, Steve Guttenberg walked into the showbiz haunt Crustacean on Santa Monica Boulevard in Beverly Hills. ‘I walked in and the maitre d’ made a big deal for me,’ said Mr. Guttenberg. The Goot — as he’s known to his friends — appreciated the show. To hear him tell it, eating in public in Los Angeles is a dangerous business for an actor whose last box office hit was Three Men and a Baby in 1987.

“All of a sudden, the maitre d’ says, `Get out of the way!'” said Mr. Guttenberg. “And they literally threw me to the side and Tom Cruise came in. And he sat Tom Cruise and said, `I’m so sorry, but you know, Tom Cruise.’ And I’m like, `Holy fuck.’

“So after three decades in L.A., he bought a place on the Upper West Side. ‘I came to New York to find a better life,’ he said. Uprooting took some time. The 15-year-old golden retriever he loved dearly was old and sick; the golden died a month ago. So two weeks ago, the wavy-haired, Brooklyn-born 49-year-old actor, who describes his career as a ’32-year-overnight success,’ finally made it back to New York City.

“‘In L.A., I think about what I don’t have,’ he told me. ‘In New York, I think about what I do have. And I’m really tired of comparing myself to Tom Cruise.” — from Spencer Morgan‘s 7.15 N.Y. Observer article, “Look Out, New York Ladies — The Goot Is Loose.”

Milk at NYFF?

Besides the possible inclusion of Clint Eastwood’s Changeling and Ari Folman‘s Waltz With Bashir, Variety‘s Winter Miller claims that “industry insiders suggest pics on this year’s shortlist for the New York Film Festival may include Gus Van Sant‘s Milk…”if it’s finished in time.” Sounds doubtful. If it happens, though, Milk won’t play Toronto…right?

The other hot possibles, Miller says, are Steven Soderbergh‘s two-part Che (yeah, heard that); Charlie Kaufman‘s Synecdoche, New York; one of Claire Denis’ two films, 35 Rhums or White Materials; Sam Mendes‘ Revolutionary Road (really?), John Hillcoat‘s adaptation of Cormac McCarthy‘s em>The Road; Ron Howard‘s Frost/Nixon and John Patrick Shanley‘s Doubt.

Anne Thompson chimes in also: “Neither Sam Mendes‘ Revolutionary Road nor John Patrick Shanley’s Doubt will be ready for the NYFF, as previously reported here. Gus Van Sant’s Milk, starring Sean Penn as Harvey Milk, will also not be finished until late October or early November, while John Hillcoat‘s film version of Cormac McCarthy‘s The Road, starring Charlize Theron and Viggo Mortenson, will not be complete until December.

“As for Che, I hear that it will only turn up at a fest willing to screen it as a 4 1/2 hour feature, as Cannes did.”

Off To The Races

Congrats to Paramount exec marketing/publicity vp Mike Vollman for snagging the twin posts of exec vp marketing for MGM/UA and marketing president for United Artists. MGM chairperson Mary Parent did the hiring.

Mike Vollman

Variety‘s Michael Fleming reported this morning that Vollman informed his Par bosses last night. Fleming adds that since Vollman “worked closely with Terry Press at DreamWorks, the hire will only accelerate speculation that she is in line for the top post, which has been the rumor for months.”

Vollman will immediately begin working with Parent and UA topper Paula Wagner on Valkyrie, Jim Sheridan’s Brothers, Perfect Getaway and How to Lose Friends and Alienate People.

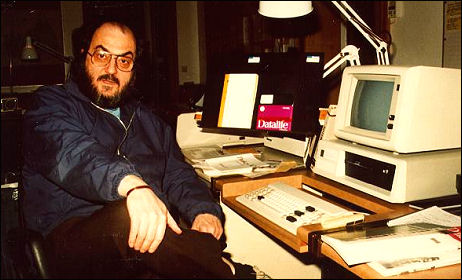

The Look Years

As long as we’re on a Kubrick jag, I happened upon this while searching for the Stanley Kubrick’s Boxes installments. I’ve heard it, I think, on that Taschen audio disc that came with that Kubrick coffee-table book, but I’ve never seen it accompanied by footage. Here’s Part 2, Part 3 and Part 4. I love hearing Kubrick admit that his senior class grade average was 67, which, in 1945, prevented him from getting into even the lowest-calibre college due to all the soldiers pouring into schools on the G.I. bill.

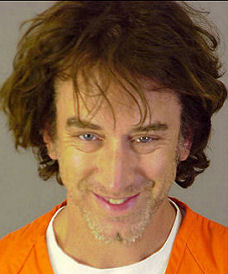

Orange Wild Wings

An “extremely intoxicated” Andy Dick was arrested this morning by California cops on drug and sexual battery charges, says The Smoking Gun. Dick, 42, was popped about 10 hours ago in Riverside County after he allegedly groped the breasts of a 17-year-old girl, etc. The incident occurred outside a Buffalo Wild Wings restaurant. Two lessons: (a) addictions will ruin your life, and (b) don’t smile like some demonic character out of a Batman film (or like the great John Barrymore in 1920’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde) when they take your mug shot.

Andy Dick, John Barrymore

Can We Have A Taste?

Why does this review of Stanley Kubrick’s Boxes, the recently-aired, British-produced doc about the legendary filmmaker’s pack-rat belongings, by thelondonpaper‘s Stuart McGurk makes no mention of the allegedly terrific behind-the-scenes footage of Kubrick working on Full Metal Jacket?

Prosthetic head of the female Vietcong sniper killed at the end of Full Metal Jacket. Kubrick allegedly shot (but of course didn’t use) footage of Adam Baldwin’s “Animal Mother” slicing it off with a machete after her death in the burned-out building.

Joncro, an HE poster from London, saw the show and posted on 7.15 at 3:34 pm that the FMS footage is “fascinating” and “hilarious, with Kubrick arguing with the English crew about how many tea breaks they are having.” He also mentioned a Lolita screen test.

Asking it before, asking again: when will this doc show in the States, when will it be marketed on a DVD, how can it be viewed online, etc.? And what about the other documentary called Citizen Kubrick, which has also been shown/screened in London? If Warner Home Video has first dibs, a voice is telling me we won’t see these docs for a long time.

Stanley Kubrick’s Boxes is a record of journalist Jon Ronson “[trawling] through the thousand-plus boxes of personal paraphernalia Kubrick left after his death in 1999.”

In this 1984 shot, Kubrick poses with a just-purchased, brand-new, hot-off-the-factory-line, state-of-the-art IBM computer.

Another guy named Bernd Eichhorn‘s also sifted through the Stanley Kubrick Estate, going through close to 1000 boxes, searched cellars and attics, collected memorabilia, photographs, objects, scripts, books and paperwork.

The contents of 977 boxes are now the basis of the Stanley Kubrick Archive, which is housed at the University of the Arts London.

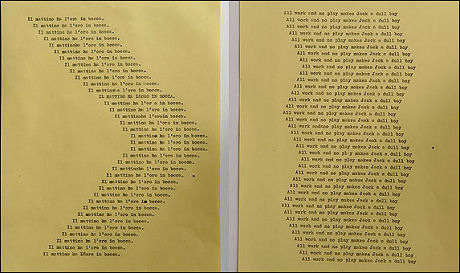

Italian and English-language versions of Jack Torrance’s demented writings in The Shining — Kubrick reportedly had versions shot in every major language.

Fake ID

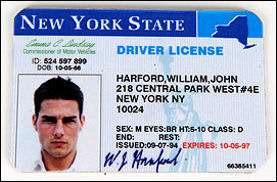

It’s a measure of Stanley Kubrick‘s exactitude that he had this New York State driver’s license made up for Tom Cruise‘s William Harford character, which might have conceivably been used for an insert shot in Eyes Wide Shot. (No such shot turned up in the final cut.) Except if Kubrick was really a detail freak, he’d have made the expiration date on the license the same year as EWS‘s expected release date (i.e., 1999) or beyond, and not October 1997.

And the fact that license says Harford’s height is 5’10” while most celebrity height sites put Cruise’s stature at around 5’7″ tells you Kubrick was not above sacrificing reality on the altar of flattery.

The Harford license is one of the hundreds of items in the currently viewable Kubrick Archives in London.

Best Take Yet

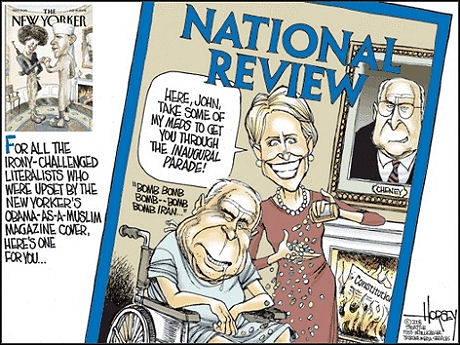

A Tom Toles cartoon in today’s Washington Post, passed along by HE reader SpinDozer:

Herzog as Hitler!

The Playlist author[s] have come up with some reasonably on-target casting suggestions for Quentin Tarantino‘s Inglorious Bastards. Except for one that’s sounding less and less right plus one flat-out wrongo. They also contain one amazing suggestion, which is Werner Herzog playing Adolf Hitler. A master stroke, genius, stuff of instant legend…especially if Herzog plays Hitler with his own voice and manner and doesn’t try to be Bruno Ganz in Downfall.

Potentially the most audacious casting all of the 21st Century.

As I wrote a few days ago, I’m starting to think that Brad Pitt as Lt. Aldo Raine is a mistake. As a sage HE reader-whose-name-I’ve-forgotten pointed out, Pitt needs to play Landa, the German Colonel “Jew Hunter.” Aldo has a strong presence in the first act, but then becomes a secondary character, and Landa is the best part in the script, hands down. How hard will it be to learn to say 40 or 50 lines in convincing German? Even if Pitt can’t do it well enough to fool German-speaking natives, who cares? This is a “movie” that cares nothing for genuine realism.

The others with comments:

3. Marion Cotillard as Shosanna Dreyfus / HE comment: perfect. 4. Isaach De Bankole as Marcel, the black projectionist / HE comment: Samuel L. Jackson instread. 5. Michael Madsen as Sgt. Donny Donowitz, a.k.a. “The Bear Jew” / HE comment: Perfect casting if this was 1987, but Madsen will be 50 in September, and he’s had some very strange facial work done besides. I like Madsen as much as the next guy, but the Jews in the platoon have to at least be in their 30s…no? 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10. Alexandra Maria Lara as Bridget Von Hammersmark, John Hawkes as Pvt. Hirschberg, August Diehl as Frederick Zoller, Catherine Deneuve as Madame Mirieux, Tim Roth as Lt. Archie Hicox, Julie Delpy or Audrey Tatou as Francesca/ HE comment: all fine.

Forget It

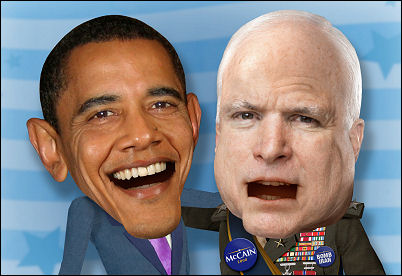

The new JibJab presidential campaign spot (which aired on Leno last night) is a retrograde, woefully cornball, second-tier thing at best. “My Land” was a huge phenomenon four years ago, but this time out the JibJabbers guys are mainly trying to recycle and photo-copy. What kills it for me is (a) a yokel-cornball streak a mile wide and (b) a sophmoric and simplistic anti-Obama attitude.

The new spot is called “Time For Some Campaignin'” (a riff on Bob Dylan‘s “The Times They Are A Changin'”). The rhetorical point is that politicians do the same dance every year, telling us what we want to hear, and we pay for it to the tune of billions. Generically cynical, no edge or innovation, over and out.

Flaw #1: they’ve used a twangy-ass banjo again, aping the country tone of the “My Land” spot. Flaw #2: the JibJab guys have no specific Barack Obama vs. John McCain point to make except for a standard contest of a hearts-and-flowers liberal vs. a snarly-voiced warmongering conservative, which is a fairly sloppy observation at this stage of the game. Flaw #3: a good 50% to 60% of the spot uses old or so-what? material — i.e., the Bushies are on their way out, a recap of Hillary’s failed campaign (an allusion to her 2012 ambitions, Bill’s randy-ness with a Monica-resembling brunette) and so on. Flaw #4: it depicts Obama as a Snow White or Bambi fantasist living in an animated Polyanna world — an allusion to the criticisms of his “Yes We Can!” phase that BHO didn’t offer specific policies — which shows the spot to be at least three or four months out of date. Flaw #5: the guy who voices Obama doesn’t sound like him in the least. Flaw #6: the guy who voices McCain sounds like a mixture of Brian Dennehy, Louis Armstrong and Foghorn Leghorn.

And the interactive online software that supposedly allows you to put your own head shot in the animated cartoon doesn’t work. I clicked on the damn green button eight or nine times.

J & C’s New Yorker cover

Illustration by the Seattle Post-Intelligencer‘s David Horsey.