Good Night and Good Luck

After reportedly trying to forge some kind of amicable, foward-looking merger between Picturehouse and Warner Independent, Warner Bros. management has suddenly thrown up its hands and is getting out of the “dependent” business altogether, it was announced about an hour ago.

WB president & COO Alan Horn released a statement that seems to translate, when you boil the snow out of it, into the following: “Sorry, but we’ve come to realize that running a Fox Searchlight- or Paramount Vantage-type operation just isn’t our bag. Our hearts were sort of into this, but now they aren’t. Things change. Besides, we’ve got New Line for the smaller stuff. We’re into maximizing revenue and building broad genre franchises, and…you know, making or releasing movies for people who read reviews and enjoy provocative subject matter just isn’t worth it to us.”

The actual statement reads that “with New Line now a key part of Warner Bros., we’re able to handle films across the entire spectrum of genres and budgets without overlapping production, marketing and distribution infrastructures …after much painstaking analysis, this was a difficult decision to make, but it reflects the reality of a changing marketplace and our need to prudently run our businesses with increased efficiencies. We’re confident that the spirit of independent filmmaking and the opportunity to find and give a voice to new talent will continue to have a presence at Warner Bros.”

So except for Clint Eastwood‘s Gran Torino and the occasional lucky-accident movie that may rank as award-worthy, Warner Bros. seems to have basically taken itself out of the quality-driven prestige movie business.

I wonder what really happened? What led to the breakdown of the merger talks?

It turns out that Defamer‘s Stu VanAirsdale was fairly close to the money when he reported that Picturehouse may soon be shut down, and that Anne Thompson‘s Variety story about the same situation was less correct, especially in reporting that Picturehouse chief Bob Berney and Warner Independent prexy Polly Cohen are “likely” to accept a bicoastal power-sharing arrangement that will preside over a merged operation,” i.e., Warner Indiepicturehouse.

Another One…C’mon!

Glenn Kenny, one of the country’s finest film critics and a brilliant writer to boot, has been cut loose by Premiere.com. “What this means for this blog is still up in the air,” he wrote this morning. “I’ve got meetings this afternoon in which such things are to be negotiated. In any case, I now join the ever-growing ranks of film critics without staff positions. I very much hope to keep this blog going…and get some good freelance work, quick. Anybody with ideas in this area should contact me at glennkenny@mac.com. Hope to be in touch again soon. Thank you, you’re the best goddamn audience a blogger could ever have.”

Thursday Tracking

Speed Racer (opening Friday) is running at 90, 29 and 16, which looks to me like $25 to $30 million, at best. (Normally a 16 first choice means $15 to $20 million, depending on the demographic, but the family-trade current will kick this one up.) What Happens in Vegas is running at 87, 32 and 18. David Mamet‘s Redbelt is going wide this week with 20 general, 24 definite interest and 2 first choice. The Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian (opening 5.16) is at 96, 42 and 14. Sex and the City (New Line, HBO, 5.30) is at 84, 23 and 6, but among over-25 women the first choice is 14, so it’ll probably play The Devil Wears Prada.

Harvey’s Tough Move

“In a heated phone call with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi late last month, Hillary Clinton supporter Harvey Weinstein threatened to cut off campaign money to congressional Democrats unless Pelosi embraced a new plan by the movie mogul to finance a revote of the Democratic presidential primaries in Florida and Michigan, according to three officials who were briefed on the contents of the conversation.” — filed this morning by CNN White House correspondent Ed Henry.

Great White Hope

Yesterday’s Grand Wizard award went to Hillary Clinton for blatantly using the term “white Americans” in a USA Today interview written by Kathy Kiely and Jill Lawrence. “I have a much broader base to build a winning coalition on,” she said, citing an Associated Press article “that found how Sen. Obama’s support among working, hard-working Americans, white Americans, is weakening again, and how whites in both states who had not completed college were supporting me.”

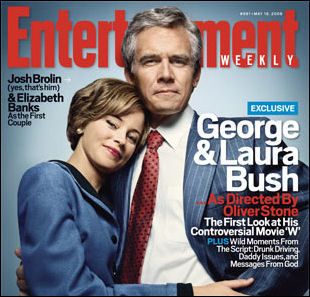

Brolin’s Bush

”Bush may turn out to be the worst president in history,” W. director Oliver Stone has told Entertainment Weekly . ”I think history is going to be very tough on him. But that doesn’t mean he isn’t a great story.

Josh Brolin, Elizabeth Banks as George and Laura in Oliver Stone’s W.

“It’s almost Capra-esque, the story of a guy who had very limited talents in life, except for the ability to sell himself. The fact that he had to overcome the shadow of his father and the weight of his family name — you have to admire his tenacity. There’s almost an Andy Griffith quality to him, from A Face in the Crowd. If Fitzgerald were alive today, he might be writing about him. He’s sort of a reverse Gatsby.”

Again, my reactions to Stanley Weiser‘s fine script.

Generation Gap?

I wasn’t going to say anything and just wait until the 5.18 screening of Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull in Cannes, but since Ain’t It Cool has run a neg review from “ShogunMaster” (and since Hollywood Wiretap has linked to it), the cat is out of the bag and I may as well share something of my own.

Last night I heard from a guy I’ve known for years who’s quite friendly with an exhibitor from the southern region, and this guy passed along some comments after seeing an exhibitor screening two days ago. The exhib’s taste in movies tends to be fairly generous and populist (enjoyed Iron Man, even liked Speed Racer), but he wasn’t especially taken with Indy 4, my friend says.

The most interesting thing my source passed along was his friend’s sense that “the only ones who liked it were the older guys.” This ties in to an older-younger, march-of-time theme that is certain to seep through. Harrison Ford‘s Indiana Jones is obviously older, Steven Spielberg is an older guy who is proud of shooting and cutting action films in a somewhat old-fashioned (i.e., classic, non-Matrix-y) way, and now — maybe — a hint that the film itself may play older, or on some level embody older-ness. Cool.

A Hollywood screenwriter guy is telling me that “people” — he didn’t say younger or older, but let’s presume the latter — “are really liking it.” He claims there was another exhibitor screening last week, and that some feel “it’s the best of the sequels.” It has, he’s been told, a kind of reflective, summing-up quality that has echoes of Temple of Doom and The Last Crusade.

I love this. Especially having been pummelled by Speed Racer last night. I would love it, I mean to say, if Indy 4 winds up providing a window into the Spielberg- Lucas-Jones mindset — i.e., we’re obviously grappling with the world as it is and giving it hell, but we’re still older guys and very comfortable, thank you, with doing things in our own tried-and-true way.

Let’s leave it alone for now, but the two downbeat responses suggest that a Da Vinci Code-like mauling could happen — maybe, possibly — when Mr. Jones turns up at the Grand Palais on 5.18. I’m thinking again about the statement that producer George Lucas gave to USA Today‘s Scott Bowles, the one about it “not” being “the Second Coming…it’s just a movie, just like the other movies.”

This may turn out to be a good thing, in a way. If this talk keeps up expectations will be slightly lowered by the time it shows in Cannes (and in domestic media screenings) on the Sunday after next, and the responses may therefore fall under the heading of “pleasant surprise.”

Whoa…

Decompressing from Speed Racer at Leow’s IMAX — Wednesday, 5.7, 8:55 pm

Double Negative

“The big question if Clinton stays in the race is this: Just how will she campaign? Yesterday, there were no negative TV ads or attack mailers. But Clinton did stress that she can win the general, implying that Obama might not be able to.

“‘I have a much broader base to build a winning coalition on,’ she told USA Today, citing her support with white working-class voters. It’s comments like that one that might drive more supers toward Obama pretty quickly. Why? Because they know the math, but they don’t want her to spend three weeks making a case that Obama can’t win. It will only weaken him.

“Here’s what Obama backer Chris Dodd said yesterday, per NBC’s Ken Strickland. ‘You’re going to be asking a bunch of people [in West Virginia] to vote against somebody who’s likely to be your nominee a few weeks later? And turn around and ask the very same people a few weeks later to reverse themselves and now vote for [Obama] on election day?'” — from this morning’s edition of MSNBC’s First Read.

The Gods Make Mad

I admire and respect the moves and the intent of Speed Racer (Warner Bros., 5.9), which I saw last night at the Leow’s IMAX near Lincoln Center. Right away I was saying to myself, “All right, this is out there….infuriating but brilliantly out there.” But it offers almost nothing in the way of genuine personal charm (except for the monkey, Chim-Chim) and I began looking at my watch starting around the 45-minute mark. Honestly? More like a half-hour in.

This is a deranged, steroid-cranked family-action movie…the work of madmen — undeniably brash and looney and, I feel, desperately in need of a quaalude. Speed Racer is a piece of very audacious, high-quality….I was going to say “torture” but it’s not. It’s extremely nervy filmmaking, clearly, but the Wachowskis are way too caught up in fulfilling their “we’re cooler than any of you!” vision and in being at least two if not three giant steps in front of everyone else in terms of creating a new film vocabulary in order to explore and shake the cage while ostensibly telling a story, and a lame-ass one to boot.

The Wachowskis are so zonked by the design dreams in their own heads that they’ve delivered a new kind of monster-budget insanity. They’ve made this movie for themselves, first and foremost, and for open-minded (or at least fair-minded) critics, and certainly for film history…but they haven’t concurrently “served the corporation” and made a film that people over the age of 8 or 9 can settle into very easily or comfortably. Or even settle into with some effort. I didn’t sit there consumed with loathing for this thing. It’s too fascinating for that. But it’s also a movie that’s saying over and over, “Look at us! Look at what we’re doing!” It’s too breathtaking to really entertain. And as pleased as I was by the verve-and-moxie element, I was dying for it to end.

You have to throw out the rule book and accept that this movie is using an entirely different kind of spaceship and orbiting the earth in a way that is going to vaguely piss you off but at the same time dazzle you. Or certainly intrigue you. The refusal to conventionally cut or fade or wipe from one scene to another — awesome. But it’s not done in a way that gives any sort of familiar, recognizable pleasure, and as square as this sounds, you really do need some of that in a movie. You have to keep feeding and massaging the square guy while introducing the new hipster, and there’s very little square-massaging going on in this thing.

Speed Racer certainly isn’t pleasurable to sit through, character-, theme- or story-wise. In subjecting their audience to the same old pure-hearted individual contender vs. the corrupt corporation horseshit, the Wachowskis are showing their elitist-sadist colors. If it was good enough for Japanese anime and and other graphic media in its day, they seem to be saying, it’s good enough for us right now…and if you don’t like it, tough! Watching it is a bondage-and-discipline game — you feel trussed up and bound with Andy and Larry (or whatever his name is now) applying the cool whip.

But it’s more than a little ironic that for a movie that trots out the evil-corporate-mogul business for the 189th time, Speed Racer is drenched in synthetic splendor that’s been bought and paid for by corporate cash. And it’s way, way too long. It should have been a 95-minute deal, tops, but it goes on for two hours and 9 minutes.

The racing sequences are insane. You never have any idea about what’s going on. Shots don’t build or match up or pivot off each other. They collide in a kind of surreal cartoon madness. The geometric/spatial relationships between the racing competitors are almost always a complete mystery. Off with the editor’s head! And the martial arts combat sequences are nothing — fatally boring, by my book.

The performances are okay, but I found more fascination in the face of Chim-Chim than anything the humans came up with. I loved that fucking monkey, and began to really dislike — hate! — the Wachowskis for only using him for typical animal-reaction cutaway shots. If they’d only dwelled on his facial reactions for seven or eight seconds at a time (or more!). But no — over and over they do a quick Chim-Chim laugh cut and then back to Emile Hirsch or John Goodman or Christina Ricci or Susan Sarandon or the mugging, heebie- jeebie supporting players. Fuck! (And I don’t like to use profanity unless it fits.)

McWeeny & Billington

Ain’t It Cool’s Drew McWeeny was on the record with his Speed Racer rave yesterday, before David Poland. I should have acknowledged this when I posted my 5.7 piece at 1:19 pm. “I think critics are forgetting that part of our job is to not only say what we like, but to review a film based on the intent of that film,” he says. “Comparing Speed Racer to Andrei Tarkovsky or serious adult cinema is a sucker’s bet. Of course they don’t compare. But it’s one of the most outrageous visions in kid’s cinema since George Miller‘s Babe: Pig in the City. A good thing, in my book.”

First Showing‘s Alex Billington also posted positively yesterday.

“I’m actually glad to hear that you mildly enjoyed it,” he wrote this morning, “as I was expecting most people to hate it, especially with all of the commentary you had written previously. I really do think it’s a hard movie to like if you can’t step out of your own age and attempt to appreciate it for the kids movie it is. But then again, it does have its flaws and it’s impossible to get around those especially when it brings the movie down in some big ways.”