This was composed four years ago by Debbie Saslaw. Many echoes and similarities, except for one event. I could say something but I won’t.

What Triggered The Era of Homme Fatale?

We are living in the age of the male blanc dangereux, or, if you will, the homme fatale.

If there’s one thing the mainstream media and entertainment industry agree upon without hesitation, it’s that 40-plus white guys have enjoyed too much power for too long and need to be brought down.

The view is that too many of these ayeholes are anti-woke or not woke enough and therefore bad news, and that they need to ride in the back of the bus for a while and learn how it felt for marginalized people for too many decades.

Aside from your basic wokequake and #MeToo factors, I wonder if this viewpoint was in some way triggered by (or is perhaps a delayed reaction to) the ’90s femme fatale wave. All of those films about scheming, black-hearted women with ravenous sexual appetites, blah blah. What intelligent woman wasn’t quietly furious about (or at least hugely irritated by) these films, one after another after another?

The first crop of femme fatales, of course, arose with the film noirs of the late ’40s to mid ’50s. Lana Turner in The Postman Always Rings Twice, Barbara Stanwyck in Double Indemnity, Jane Greer in Out of the Past, Ava Gardner in The Killers, Lizabeth Scott in Dead Reckoning, etc.

The second manifestation happened 25 years later with Lawrence Kasdan‘s Body Heat (’80) and particularly Kathleen Turner‘s greedy and conniving Matty Walker. This wasn’t exactly followed up upon by Stephen Frears‘ Dangerous Liasons (’88) and Harold Becker‘s Sea of Love (’89) but the notion of selfish, cunning and possibly dangerous women was certainly underlined by these films.

The ’90s wave, sparked by the perverse imaginings of screenwriter Joe Eszterhas, pretty much began with the one-two punch of Curtis Hanson‘s The Hand That Rocks the Cradle (’92) and Paul Verhoeven‘s Basic Instinct (’92). It more or less ended with Roger Kumble‘s Cruel Intentions (’99).

Call it a vogue that lasted seven years or a bit less.

The headliners were (1) Basic Instinct, (2) Barbet Schroeder‘s Single White Female (’92), (3) Katt Shea‘s Poison Ivy, (4) Philip Noyce, Ezsterhas and Ira Levin‘s Sliver (’93), (5) Nic Kazan‘s Dream Lover (’93 — earned a grand total of somewhere between $256,264 and $316,809, (6) Alan Shapiro‘s The Crush (’93), (7) Uli Edel‘s Body of Evidence (’93), (8) William Friedkin‘s Jade (’95), (9) Gus Van Sant‘s To Die For (’95) and Cruel Intentions — an even 10.

What am I missing? Basic Instinct 2 (’06) doesn’t count — it arrived way past the end of the cycle.

No Way Scorsese Saw “Flower Moon” As “Mississippi Burning 2”

On or about 11.5.19 I chatted with Leonardo Dicaprio at a San Vicente Bungalows party. He was particularly excited about Killers of The Flower Moon, describing it as a kind of “birth of the modern FBI” story. The basic line, he said, focused on former Texas Ranger Tom White (whom Leo was intending to play at the time) being ordered by top G-man J. Edgar Hoover to take over the Osage murders case and make sure the bad guys pay the price.

Eventually DiCaprio decided to play one of the killers, Ernest Burkhart, with Jesse Plemons stepping into the White role.

Given Leo’s summary, one could have been forgiven for presuming that Martin Scorsese‘s film, which didn’t begin shooting until April ’21, would be a “white FBI guys bring justice to Oklahoma” movie, or something in that general vein. Certainly not as fictitious or fantastical as Alan Parker‘s Mississippi Burning, as Eric Roth‘s screenplay has always been closely based upon David Grann’s scrupulously researched 2017 book. But perhaps with a certain good guys-vs-bad-guys attitude.

But between Scorsese, Grann and Roth, how could Flower Moon possibly have been made with the idea of delivering an Oklahoma version of Parker’s 1988 thriller, which ignored many facts about the 1964 murder of three Civil Rights workers and reduced the African-American characters to people who grieved, cowered and sung hymns?

But then, three months ago, along came Flower Moon costar Lily Gladstone, who, in a Variety interview with Zack Sharf, seemed to suggest that Scorsese had, up to a point, made a film that hadn’t, in fact, sufficiently considered the Osage native point of view of the killings and the investigation of same.

Gladstone said that Scorsese “worked closely with the real-life Osage Nation to ensure his movie would properly represent the community. The result was that “the Osage Nation ended up positively changing Flower Moon from what Scorsese [had] originally planned.”

Which was what? Missisippi Burning 2 or some facsimile thereof, as Eddie Ginley joked yesterday in a thread?

“The work is better when you let the world inform the work,” Gladstone explained to Sharf. “That was very refreshing how involved the production got with the [Osage Nation] community. As the community warmed up to our presence, the more the community got involved with the film.

“It’s a different movie than the one [Scorsese] walked in to make, almost entirely because of what the community had to say about how it was being made and what was being portrayed.”

Glenn Kenny: “That’s Gladstone’s perspective, shaped through that of Sharf, and in any event has nothing to do with reshoots. Scorsese and company were getting Osage input from well before the cameras started rolling.

“Look, man, I know how precious the ‘Native Americans strong-armed Scorsese into going woke’ narrative is to you, and I know you’re gonna stick with it through thick and thin, but just don’t pretend too much insider knowledge here.”

HE response: “So Gladstone misstated Scorsese’s creative strategy (i.e., before the alleged Osage Nation re-think) in order to celebrate the Osage Nation’s strength as a culture and to emphasize that their perspective on the 1920s murders was, thank God, crucially included at the 11th hour.

“You’re saying, in other words, that Scorsese had understood the entire Killers equation from the get-go, as had original author David Grann, and that neither of them needed woke tutoring as far as the Osage perspective was concerned.

“Gladstone, in short, was spinning her own impressions last January, and Sharf, a go-along wokester parrot, played along?

“Maybe so.”

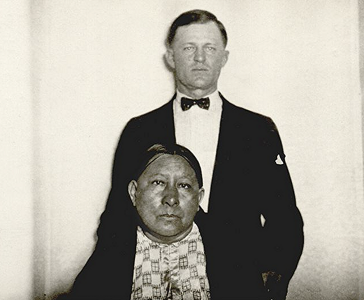

Here, by the way, is a snap of the actual Ernest Burkhart and Mollie Burkhart (played by DiCaprio and Gladstone in the film)

Good God In Heaven

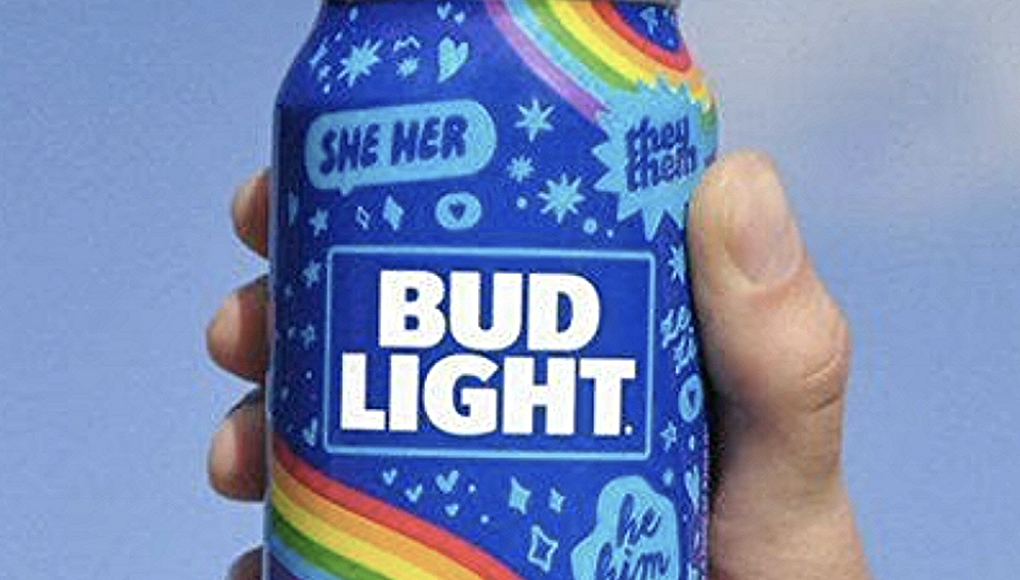

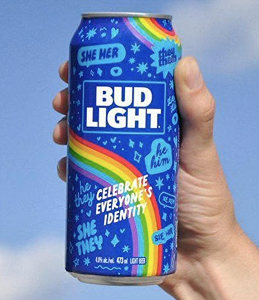

I said earlier I’ve no particular problem with Dylan Mulvaney endorsing Bud Light. But the decoration on this Bud Light can gobsmacked me. I thought inclusion was the new idea — not just beer bruhs chugging Bud Light during football games but all sizes, shapes and persuasions. But the decoration plainly says “gays and trans people only.” Sober for 11 years, I haven’t been up to speed on beer cans for quite some time.** Sorry.

Moronic “Yo Girl” Bullshit Marvel Comedy

Nia DaCosta‘s The Marvels (Disney, 11.10) will obviously be torture for a great many people.

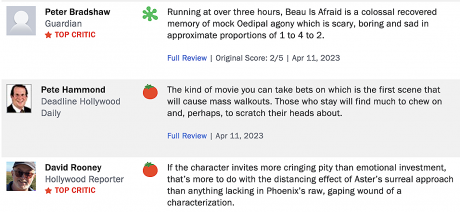

The Worst Three Hours of My Moviegoing Life

…will engulf me on Thursday evening (4.13), and all I can say is that “the clarity of mind experienced by a man standing on the gallows is wonderful.”

Although I hate certain aspects of my life and indeed myself, I do respect my willingness to sit through an IMAX presentation of Beau Is Afraid. Willingness as in hardcore manliness.

Funky, Family-Owned L.A. Beach Motels

“A new concept arrived in the 1930s, the motel — a portmanteau word made out of motor + hotel. They sprang up all over, and in the early years they were usually family owned.

“A classic example of an early bungalow-style operation was the Topanga Ranch Motel. Built in the mid ’30s and once owned by William Randolph Hearst, it was one of the first Topanga-Malibu hostelries to cater exclusively to the motorcar crowd.

“We know a screenwriter who would stay at the Topanga Ranch Motel for weeks in winter. [It was] a gently decaying relic, but cheap and quiet and there were no distractions — just a TV that only received three stations on a good day. But by then, the era of the motel was over.”

— from an excellent piece in Topanga New Times, dated 11.4.22 and titled “Hotel California.” Written by Suzanne Guldimann.

Jeff & Sasha Substack: Hold Out Until Cannes

Sasha and I were chatting yesterday in a general sense, this and that and whatever. The subject eventually drifted into “what’s out there that sounds good…something that might heat up the blood?” We discussed some of the big attractions at the ‘23 Cannes Film Festival (the slate will be announced on Thursday, 4.13), and for whatever reason I forgot to mention that I’ll be submitting to both Renfield and Ari Aster‘s Beau Is Afraid that same day. I also didn’t mention HE’s most eagerly awaited pre-Cannes film, which is Matt Johnson and Matthew Miller‘s BlackBerry (IFC Films, 5.12). Anyway…

Sensitivity Editing (i.e., Censorship) for Plays

The gist of Martin McDonagh‘s recently-aired beef is that certain theatrical producers want words in his 2003 play The Pillowman, set for a revival presentation in London two months hence, so be diluted to as not to offend woke audience members.

McDonagh to BBC’s Today: “They wanted to make some words more palatable to them or what they think their audience is. It seems like governments are becoming increasingly more scared of dissenting voices,” which makes this “a very frightening time.”

McDonagh #2: Writers should “get off social media”, “stop checking the internet” and “go out and outrage.”

In other words theatrical producers are urging the same kind of sensitivity editing that has afflicted the publishing industry.

Good Shootin’

When I first saw Triple Frontier in early ’19, I didn’t process it as a comfort film. A good one, especially the second half, but not a repeater. I’ve watched it at least five or six times since. So it’s a comfort film, I guess. Except for the ending. My issues are explained within the last four paragraphs.

I was looking for a video clip of one the most vivid scenes, when a portion of a narrow cliffside trail crumbles and a poor overloaded mu goes over the side. Mesmerizing. They either created a donkey dummy and threw it over a cliff, or created the moment with exceptional CG.

Posted on 3.6.19: I was into Triple Frontier during the first half, but not exactly gripped by it.

We aren’t told very much about the five ex-commandos (Affleck’s character is sketched out to some extent — he’s fat, financially strapped, has an alienated daughter) and the general feeling is that the film is a stone skipping across the surface of a lake. Or, you know, more into treading water than actually swimming.

The key moment is when they discover that the drug lord has much, much more cash socked away in his jungle abode than expected. $250 million or something like that. If these guys could get away with $10 million each they’d obviously be doing just fine. Hell, they could make off with $20 million each. But no — cash-strapped Affleck suddenly wants a Kardashian-sized bank account. He not only loses his mind — let’s take it all, look at this, we’re loaded beyond our wildest dreams! — but everyone else falls in line.

The problem is that Oscar Issac has arranged for a large Russian-made chopper to take them over the Andes, but all that extra dough (bags and bags of it) weighs a hell of a lot, and they find out too late that the helicopter can’t manage to clear the 11,000-foot Andes peaks with all that weight. The chopper goes down, and then, finally, Triple Frontier gets interesting.

Gripe: More than anyone else, Affleck’s character goaded the team to carry off a lot more money than they had originally planned to find, etc. Everyone went along with this, but Affleck leads the charge, urging them on.

Taking more money makes no sense as there are clear weight limits on the amount of cash the chopper can carry over the Andes. The pilot (Pedro Pascal) voices concerns about this, but they’re all so money-crazy they decide to risk it anyway.

So after Affleck dies and the others make it back safely, they decide to DONATE THEIR SHARES to Affleck’s family fund. The principal recipient is Affleck’s chubby daughter, a typically sullen teen who refuses to face life without ear buds.

I would make sure the daughter gets a full one-fifth share of the loot, naturally, but why does she get all of it? I really don’t get this at all. Affleck inspired the team to think and act in greed mode. He was the father of it. How does that translate into the fat daughter pocketing every last dime?

Statement of Values

Spoiler whiners are little babies whose sole…okay, primary concern is subject matter (i.e., “then what happens?”).

You’ve gone through college and decades of living and struggling and you still don’t understand that subject matter is oatmeal?…a thing to start with but also a form of confinement if you allow it to run things? It’s the lowest and most rudimentary form of absorption and processing that a film or streaming-drama viewer can possibly know. For peons only.

But to the whiners subject matter is their Lord and Ruler…a flag, a way of life, a Gregorian chant. To 95% of viewers, subject matter is damn near everything.

Around 11 pm last night somebody told me what had happened on Succession, and urged me to watch episode 3 straight away. Firstly I thanked them, and secondly it only whetted my appetite.

Having been tipped off didn’t affect my enjoyment of any of the elements (story, acting, dialogue, visual strategy) IN THE SLIGHTEST WAY. Do you know why? Because I’m not an infant. Because I’ve achieved a semblance of an adult perspective in my life.

A teenaged friend once spoiled the ending of Nicholas Ray’s King of Kings (‘61). Not just the crucifixion part but the resurrection stuff…all of it. I’ve never forgiven him.

“The singer, not the song”…shut up! Bastard! I don’t want to know you!

However, HE’s basic limited spoiler avoidance policy (i.e., always wait two weeks after a film opens unless everyone else has already spoiled it) remains in place. Same policy regarding shocking plot turns on extended streaming series (i.e., mum’s the word for two weeks unless it’s been spoiled by everyone else right away, in which case it’s fine to jump into the pool).

HE’s Cannes Film Festival policy is to exercise restraint whenever appropriate, but if everyone else spoils I’m not going to hold out.