Barbet Schroeder‘s Reversal of Fortune (’90) delivers one of my all-time favorite endings, which isn’t an “ending” as much ironic commentary about the mindset of a rich, very blase sociopath (Jeremy Irons‘ Claus von Bulow) and the difference between the “little people” and the Fifth Avenue elites who occasionally pop into this or that store. The scene happens between :50 and 1:25. HE comment: The checkout clerk had it coming because she was so unsubtle when she stared at the front page of the New York Post. She did it so blatantly that she forced Von Bulow to respond.

Straight Monkeypox Dope

Mainstream media reporters and editors are generally forbidden…okay, discouraged from filing the kind of straight-from-the-shoulder Monkeypox report that Donald McNeil, the highly respected chronicler of pandemics who reported for The New York Times for decades, has posted on Common Sense.

Excerpt #1: “At the moment, unless you are a gay man with multiple or anonymous sex partners, you are probably at not much risk.”

Excerpt #2: “There are two effective vaccines for this disease and one solid treatment, [so] why are we losing the fight? I blame shortages of vaccines and tests, the initial hesitancy by squeamish health agencies to openly discuss who was most at risk, and the refusal of organizers of lucrative gay sex parties to cancel them over the past few months, even as evidence mounted that they are super-spreader events.”

Cold Cards

Congrats and best wishes to the newly-betrothed Ben Affleck and Jennifer Lopez, but getting hitched in Las Vegas…I’m sorry to say this but Las Vegas is no place to exchange vows.

A place this devoid of spirit and romance is bad karma. Getting married in a small-town city hall in Iowa is cool. Or on a rural Tuscan hilltop at magic hour. Or in a small chapel in Paris. Or on a beach in Kauai at dawn. Marriage is not a game of chance — it’s a game of trust. Exchanging vows isn’t about “wheee!” — it’s about “okay, this shit just got real.”

Affleck, a serious poker and blackjack player, has a seemingly ardent affection for Las Vegas, but the central metaphor of that town is about fairy tales and visions of power and dominance, and it always boils down to “did you beat Las Vegas or did it beat you?”

My point is that there’s something delicate and solemn and even mystical about getting married — it’s like saying a prayer together or co-writing a poem. If there’s one place on the planet earth where delicacy, solemnity and mysticism are in short supply, it’s fucking Las Vegas.

Caveat Emptor

The U.S. debut of Park Chan-wook‘s Decision to Leave (MUBI, 10.14) is a few months off, and I’m sure his devoted fans will celebrate every shot, cut and camera move of this slow-moving noir. From a technical standpoint it’s masterful, but it was understood by a certain percentage of Cannes Film Festival critics (i.e., the honest ones) that it didn’t go much further that that.

The Park Chan-wook cabal has insisted for years that the usual narrative elements that define most first-rate films don’t count as much when it comes to PCW, that he’s a world-class auteur because of his high style and excellent chops and that’s all — the same kind of rationale that floated Brian DePalma‘s boat for so many years.

Just remember what I was saying last May, which is that Decision to Leave is a beautifully shot slog if I ever saw one.

Posted on 5.23.22: With all due respect for Park Chan-wook’s smooth and masterful filmmaking technique (no one has ever disputed this) and the unbridled passion that his cultish film critic fans have expressed time and again…

And with respect, also, for the time-worn film noir convention of the smart but doomed male protagonist (a big city homicide detective in this instance) falling head over heels for a Jane Greer-like femme fatale and a psychopathic wrong one from the get-go…

The labrynthian (read: convoluted) plotting of Park’s Decision To Leave, though intriguing for the first hour or so, gradually swirls around the average-guy viewer (read: me) and instills a feeling of soporific resignation and “will Park just wrap this thing up and end it already?”

Jesus God in heaven, but what doth it profit an audience to endure this slow-drip, Gordian knot-like love story-slash-investigative puzzler (emphasis on the p word) if all that’s left at the end is “gee, what an expert directing display by an acknowledged grade-A filmmaker!”

God Only Knows

There’s a lyric in Paul Simon‘s “Slip Slidin’ Away” that’s always rubbed me the wrong way. Maybe you know what I mean and maybe you don’t…”God only knows, God makes his plan…the information’s unavailable to the mortal man.”

To which I would reply, “What information would that be exactly?”

We’re all familiar with the Christian sentiment about how we mustn’t condemn God for orchestrating horribly cruel fates for so many millions of people, and that we can’t hope to know or understand the grand scheme…oh, yeah? You think?

If you want to conceive of God as some kind of magnificent multiversian…an all-seeing, all-knowing, semi-sentient being with a personality and a deep voice not unlike the one that Charlton Heston converses with during the burning bush scene in The Ten Commandments…if you insist upon that kind of definition of God then you’ve no choice but to accept His absolute indifference to human suffering. Which he impassively lays on at every turn. With relish.

He doesn’t give a shit, in short, and the most frequently deployed tool at his command, as Aeschylus reminded, is “pain that falls drop by drop upon the heart.” Boy, does it ever!

All of this reminds me of a wonderful scene in Rabbit Hole (’10), about a couple grieving over a deceased young child. Nicole Kidman and husband Aaron Eckhart are in a group therapy session, and listening to a couple who’ve also lost a child. They’re sharing the notion that God has a plan and He needed their child so he could have an extra angel in heaven, blah blah, and Kidman just shoots that shit down like Sgt. York. Perfect.

“Life is a comedy written by a sadist” — Woody Allen.

Weeks Late to “Black Phone”

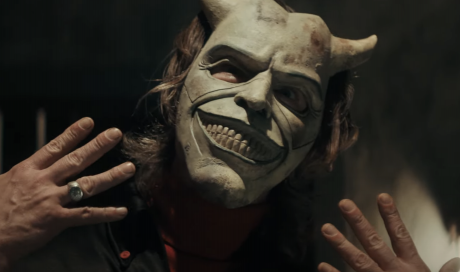

Last night I saw portions of Scott Derrickson‘s The Black Phone (Universal, 6.26). Okay, I watched the first 30 or 40 minutes, then I began nodding off, in and out. I finally gave up and escaped. It was Jett and Cait‘s decision to rent it, and I didn’t have the character or the courage to argue or suggest an alternative. I sat there in an uncomfortable position on the couch (looking up and to the left), and submitted. I have no excuse.

The Black Phone struck me as fairly awful in a hand-me-down way. And I find it hugely depressing that it’s made $105 million so far. Millennial and Zoomer-aged horror fans have no taste — they’ll sit through anything. Oh, how I hate those Blumhouse horror chops — mulchy, derivative, eye-rolling.

My feelings of distaste quickly grew into repulsion, and very early on, I should add. And this 103-minute prsogrammer is composed of horror elements I’ve seen before and didn’t think anyone would have the guts to recycle — late ’70s suburban milieu, a child-killing, mask-wearing fiend in the Pennywise/Buffalo Bill/Freddy Krueger mold (aka “the Grabber,” a take-the-money-and-run performance by Ethan Hawke), a good-hearted but cowardly young hero (Mason Thames), a young girl with Shining-like psychic abilities (Madeleine McGraw), a cellar dungeon where the Grabber imprisons his victims (The Silence of the Lambs), doltish detectives, a boozy and abusive dad (Jeremy Davies). And it’s based on a short story by Stephen King‘s 50-year-old son, Joe Hill.

Derrickson and co-screenwriter C. Robert Cargill push every button and yank every lever they can think of, and very little amounts to anything I would call unnerving or even half-scary. Talking to The Grabber’s dead victims on a dead phone isn’t scary at all — it’s just “oh, okay, a device.” I counted two mild jolt moments. (Or maybe I dreamed them.) The feeling of being fed the same old mid-teen suburban horror tropes is terrible…it makes you feel trapped and drugged and humiliated. I wanted Davies’ scum-dad to somehow die, and I consider it ludicrous that (according to the Wiki synopsis) he ends up apologizing for his brutality.

The fact that moviegoers routinely buy into films of this calibre…I don’t want to think about it. But anyone who watches this film and says “hey, not bad”…that person is not in a good place, cinematically speaking.

Red Skelton Hour

“A massively scaled and interoperable network of real-time rendered 3D virtual worlds that can be experienced synchronously and persistently by an effectively unlimited number of users with an individual sense of presence and with continuity of data, such as identity, history, entitlements, objects, communications and payments.” — an improvised, off-the-cuff, extremely loose-shoe definition of the metaverse, shared by one Clem Kadiddlehopper while regarding a traveling display of John Deere equipment in Garden City, Kansas, on Saturday, July 9th. and with a piece of hay between his teeth.

Seriously — the above definition, posted on 7.14.22, is from Puck’s Matt Belloni.

Genetic New Jersey Thing

Fascinated by the suburban faces wandering through The Mall at Short Hills. Many if not most — a good 65% to 75%— look like characters from The Sopranos. Members of Tony’s golf club, friends of Carmela’s, diners at Artie Bucco’s, prosecutors, attorneys, customers at Bada-Bing and Satriale’s, etc.

Having Endured “Gray Man”

…but also having avoided writing my review, I’ll just say that a director (or directors in this instance) can list several classic films as influences, and that’s fine. But given the Russo Brothers list, it’s fair to note the seeming presence or absence of traces of these films in The Gray Man itself. All I can say is “wow.” Okay, I’ll say more than this. Influence–wise, The Gray Man contains not so much as a hint of a trace of a whisper of Francois Truffaut’s Shoot The Piano Player (‘62). Ditto Michelangelo Antonioni’s Red Desert (‘64). There is one and only one noticable influence upon this film, and that is the Bourne franchise…finito, mike drop, over and out.

Another Reason

One of the factors behind Beanie Feldstein’s decision to leave Funny Girl early (her last performance will be on 7.31) was her history of having missed performances due to this, that and whatever. And now…tonsilitis!

Reviews That Tore It

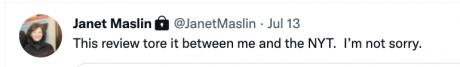

I’ve always loved Janet Maslin‘s writing, and especially her film reviews. She became a film critic for The New York Times in 1977, and then the paper-of-record’s top-dog critic on 12.1.94 when the long-serving Vincent Canby (1969-1994) moved on to theatre reviews.

Maslin covered the celluloid waterfront for five years, and to this day I vividly recall reading her Titanic review on the morning of 12.19.97, and a statement at the end of paragraph #2 that James Cameron‘s epic was “the first spectacle in decades that honestly invites comparison to Gone With the Wind.”

But Maslin’s run came to a halt after the Times published her enthusiastic review of Stanley Kubrick‘s Eyes Wide Shut on 7.16.99.

Yesterday Maslin tweeted that the Eyes Wide Shut review “tore it between me and the NYT…I’m not sorry.” I’ve never heard the detailed blow-by-blow about that episode, but I’d sure like it if Maslin (who’s been a Times book reviewer for the last 22-plus years) would tell it some day.

What other film critics have had a falling-out with their editors over their opinions, or even a single film review?

I seem to recall reading that Andrew Sarris‘s 8.11.60 review of Psycho, his very first for the Village Voice, got him into trouble, but not to the point of getting whacked. “I got so many angry letters about it,” Sarris recalled decades later. “It was my first Cahiers du Cinéma review, you might say. The idea that I promulgated [was] that Hitchcock was a major avant-garde artist. Everybody knew what Hitchcock did. Most people liked him, but didn’t take him seriously. So that was the beginning [of the auteur theory].”

In June 1976 Todd McCarthy was cut loose from the Hollywood Reporter over a negative review of Ode to Billy Joe. “I filed a dismissive review,” McCarthy wrote on 4.15.20. “[It] was published, but the next day got a call from my editor, B.J. Franklin, who conveyed the news that Jethro, otherwise known as Max Baer Jr., the director of the film, was not a bit pleased with my notice. Would I perhaps consider taking another look at it with an eye to revising my opinion upward?

“When I refused this opportunity, B.J. proposed that I interview Max about the film. I politely declined. The next day I was informed that my services would no longer be required at the Reporter, and also learned that Max and B.J. were Bel-Air-circuit social friends.”

In 1991 Washingtonian editor Jack Limpert vehemently disagreed with Pat Dowell‘s positive review of Oliver Stone‘s JFK. On 2.11.17 Washington Post columnist John Kelly wrote that “it’s not clear if Limpert showed Dowell the door or if she found it on her own.” Limpert later said that JFK was “the dumbest movie about Washington ever made.”