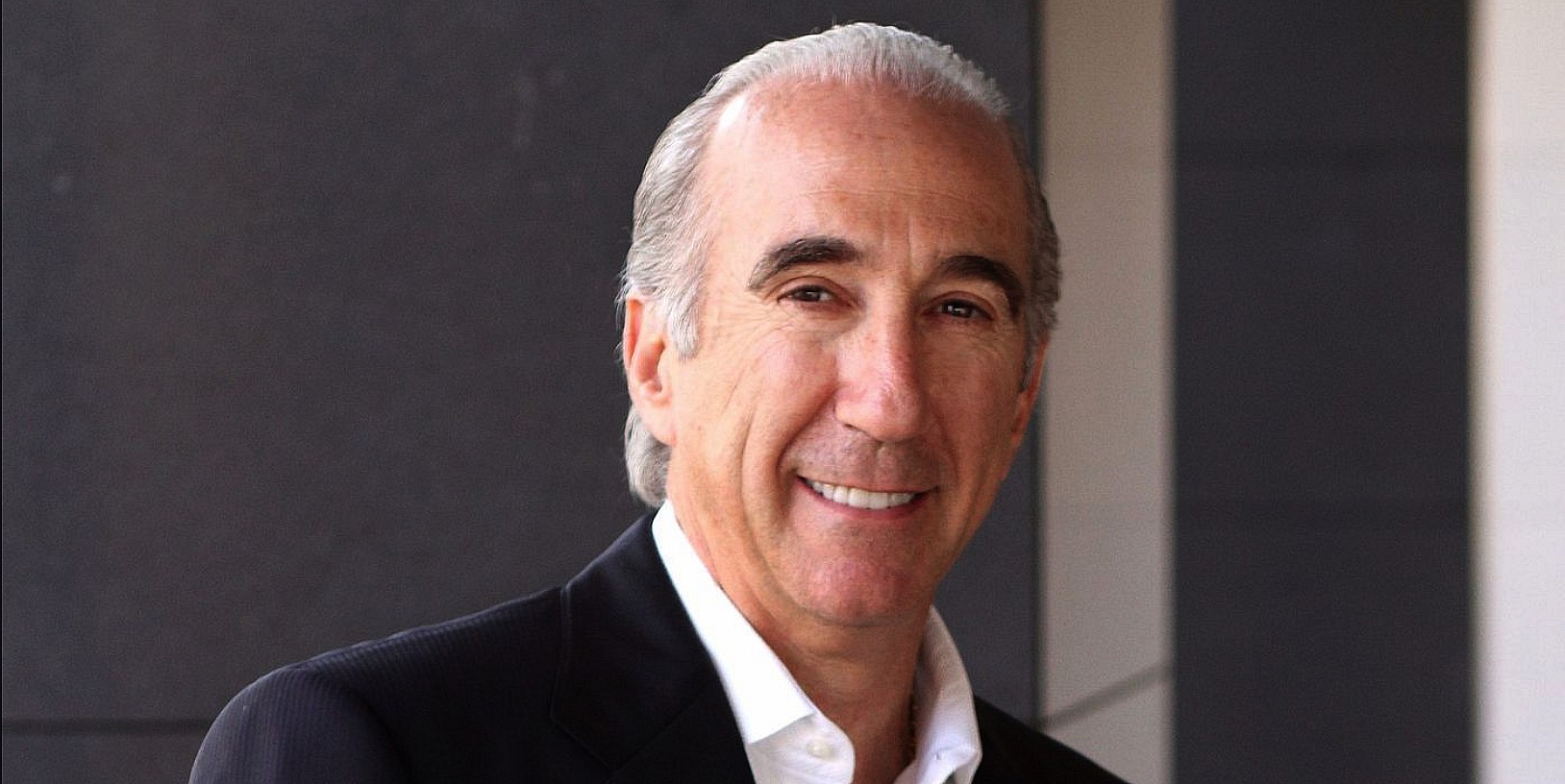

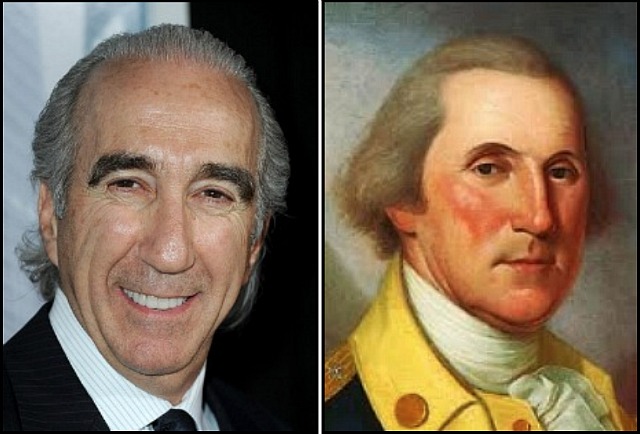

Gary Barber, the narrow-faced, George Washington-resembling chairman/CEO of MGM and MGM Holdings Inc., has been whacked or, put more politely, “asked to leave.” Deadline‘s Anita Busch has reported that MGM Holdings deep-sixed Barber, who had run the company since 2010 and had four years to go on his current contract, “over disagreements on strategy about the future direction of the company,” whatever that means.

Hollywood Elsewhere says that Barber’s dismissal is an emotionally satisfying thing. Barber may have rejuvenated MGM to some extent and he may have been loved by his now-former employees, but he was an arrogant asshole when it came to the faith and creed of film restoration. For at least the last four years Barber stood in the way of the way of Robert Harris‘s attempt to independently fund a restoration of John Wayne‘s The Alamo — a thoughtless and callous act from any responsible perspective.

(l.) Former MGM chairman & CEO Gary Barber; (r.) George Washington sometime during the French and Indian War.

Yes, outside the Alamo situation Barber appeared to be a smart, aggressive, well-organized exec who knew how to get things done. Great. Then why did he show such callous disregard for the condition of a not-great but generally respected film that could have been saved in its original 70mm form, but is now lost for the most part? What kind of South African buccaneer, unwilling or unable to spend MGM’s money to restore the 70mm version of Wayne’s film, refuses to allow a restoration of said film to be independently funded?

12.26.14 quote from a “Save The Alamo Facebook page: “Gary Barber is the worst thing to happen to MGM since Jim ‘The Smiling Cobra’ Aubrey systematically sold off the old company in the early 1970’s. Worse, the film library is at stake this time. MGM seems intent on not only having no interest in restoring and preserving [The Alamo], but in actively seeing it destroyed. Unbelievable that this kind of practice is still going on.”