It was during a discussion this morning about David Caruso that it hit me. For a minute or two in ’93, when the carrot-haired Caruso was riding high with NYPD Blue and after his bravura performance as Mike the Chicago detective in Mad Dog and Glory…for a while there it looked like Caruso might pole-vault onto the next level and become a superstar. Maybe. It seemed possible.

But of course it wasn’t. Because freckly, ginger-haired guys can’t be superstars. They can be admired or even worshipped for their acting chops (i.e., Phillip Seymour Hoffman) or respected or “popular” as far as it goes, but they can’t be “the alpha guy“…that charismatic, rock-solid, center-of-the-universe force field whom other guys want to be and women want to go out with…to be a real movie star you need to exude a certain extra-cosmic, triple-dimensional quality.

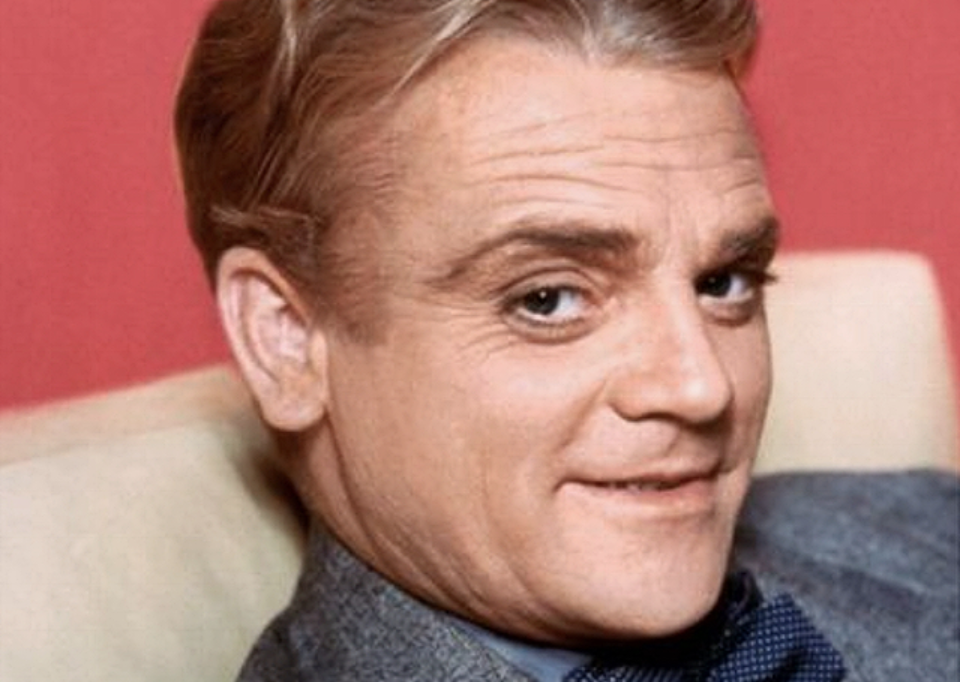

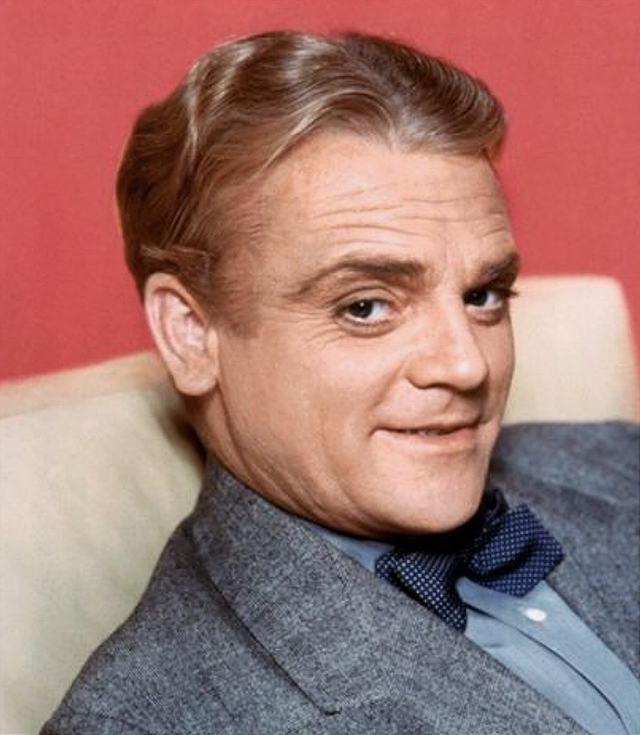

And the fact is that only two copper-haired actors in the entire history of Hollywood have become serious superstars — James Cagney and Robert Redford.

Except Cagney doesn’t really count because he ascended and enjoyed his big-star heyday in the mostly monochrome ’30s and ’40s, and so no one was obliged to contemplate his hair color or freckly complexion.

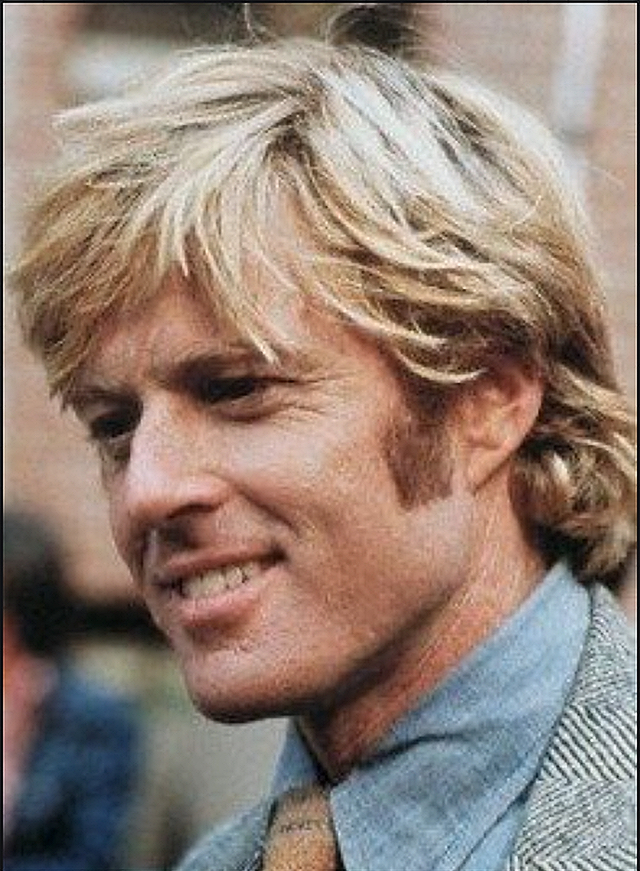

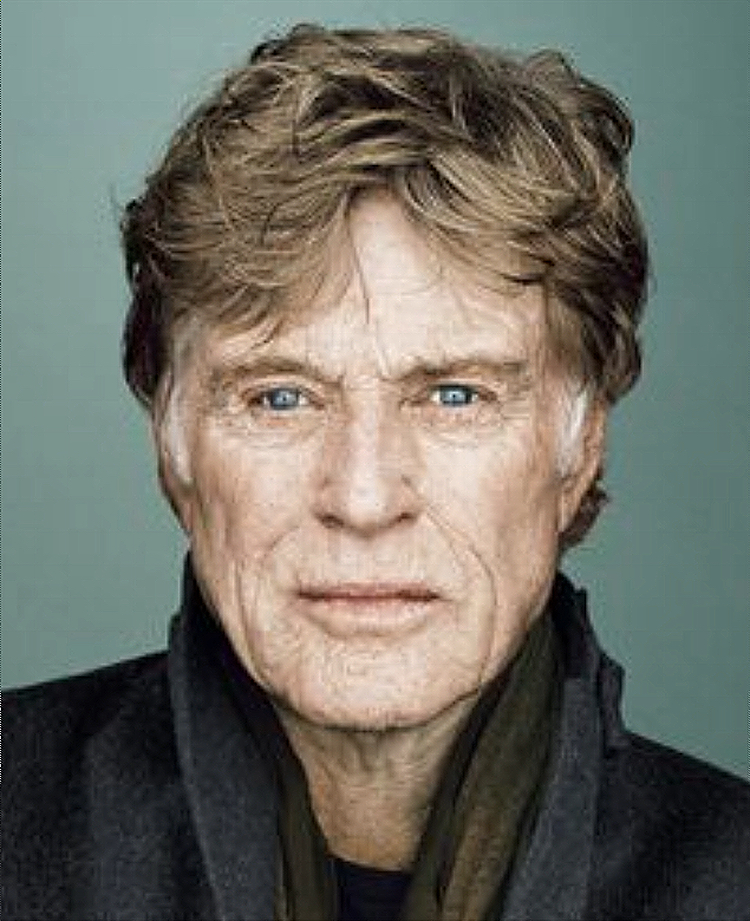

And Redford doesn’t really count because, as we all know, he became a blonde sometime in the early to mid ’60s and stayed that way until his downshift period began sometime in the late ’80s or early ’90s.

And why do you think he became a blonde? Ask yourself that. Okay, I’ll tell you why. He became a blonde because he wanted to be big, and he knew (or his agent or some good friend persuaded him) that it wouldn’t happen unless he did something about his hair. I recall talking to an old friend of Redford’s on the phone once, a guy he used to hang out with in Van Nuys, and this guy told me that Redford’s high-school nickname at the time was “Red.” But eventually he let the blonde thing go. I know that he walked around as a natural copperhead when he was hosting the Sundance Film Festival in the ’90s.

Ginger or copper-haired actresses have never had the slightest problem in Hollywood, of course. And a select few (as with anything else) have become major stars — Cate Blanchett, Amy Adams, Emma Stone, Jessica Chastain, Nicole Kidman, Julianne Moore, Bryce Dallas Howard, Isla Fisher, Lindsay Lohan, Christina Hendricks plus yesteryear’s Katharine Hepburn, Deborah Kerr, Myrna Loy, Tina Louise, Greer Garson, Rita Hayworth, Lucille Ball, Maureen O’Hara, Carol Burnett, Susan Hayward.

But ginger-haired guys have almost never made it to the penthouse level. Because there’s something about them that Americans just can’t quite settle in with or bow down to…not really. Michael Fassbender, Lucas Hedges, Paul Bettany, Jesse Plemons, Caruso, Ed Sheeran, Damian Lewis, Rupert Grint, Alan Tudyk, Brendan Gleeson, Danny Bonaduce, Eric Stoltz, Carrot Top Thompson, David Lewis, Domhnall Gleeson, Rupert Grint, Simon Pegg, Toby Stephens, the great Philip Seymour Hoffman, Chuck Norris, Jason Flemyng, Seth Green, David Wenham…none of them ever made it into the elite winner’s circle, not really. Because people glommed onto that red hair and went “okay, fine, good actor but nope.”

Yes, Leslie Howard was a fairly serious star in his 1930s heyday, but he wasn’t way up there. He wasn’t Clark Gable big.