From Scott Feinberg…

From Scott Feinberg…

Set 21 years ago in Masshad, Iran, Ali Abassi’s Holy Spider is a disturbing (to put it mildly), fact-based drama about Saeed Hanaei (Mehdi Bajestani), a serial killer of prostitutes.

The murders are ghastly enough, but a double-down comes when, post-capture, Hanaei is bizarrely supported by fanatical zealots who believe he has done Allah’s bidding.

The first half is pretty much a straightforward crime drama. After graphically depicting two of Hanaei’s grisly killings, it follows an intrepid female reporter (Zar Amir-Ebrahimi) who risks life and limb to bring about his arrest.

I can’t call this section any more than decent — efficient and good enough, but not exactly brimming with style or suspense or cinematic flair.

The diseased social reaction among his fans in the second half is what grabs you. You’re left thinking “really?…a sizable contingent of Mashhad citizens cheered a serial killer because he was helping to rid the streets of streetcorner hookers? Who thinks like that? What kind of diseased culture?,” etc.

But then of course, this is Iran and the Masshad faithful were the country’s chief bumblefucks.

The meaning of the title of R.M.N., the latest film by the great Romanian auteur Cristian Mungiu, is never revealed, or it wasn’t to me during last night’s Salle Debussy screening.

The Wiki page says that Mungiu “named the film after an acronym for rezonanța magnetica nucleara ** (‘nuclear magnetic resonance’) as the film is ‘an investigation of the brain, a brain scan trying to detect things below the surface.'”

So the film is basically about scanning the small-town minds of the residents of Recia***, a commune located in Transylvania, which most of us still associate with Dracula.

But the underlying focus isn’t vampires but racist xenophobes who fear Middle Eastern immigrants and more specifically two gentle fellows from Sri Lanka who’ve been hired to work at a local bakery.

It takes a while for the racism to emerge front and center, but a metaphorical representation is the nub of it — a phantom that lurks in the surrounding woods and more particularly within.

It manifests three times — (a) in the opening scene in which the small son of Matthias (Marin Grigore), an unemployed slaughterhouse worker, is spooked by its off-screen presence while walking in the woods, (b) in the third act when a significant characters hangs himself (also in the woods), and (c) at the very end when four or five bears are spotted by Matthias after nightfall (ditto).

R.M.N. is a meditative slow-burn parable that you’ll either get or you won’t, but there’s no missing the brilliance of a one-shot town hall meeting in which the locals are demanding that the Sri Lankans be expelled from the community.

The shot lasts for roughly 17 minutes, and it’s all fast, bickering dialogue, simultaneously burrowing into the ignorance of the townies while building and deepening and man-oh-man…it’s so fucking great that I said to myself “this is it…this is what my Cristian Mungiu fixes are all about, and thank the Lords of Cannes for allowing me, a traveller from the states, to absorb this in my well-cushioned theatre seat.

The build-up narrative is about Matthias and his mute son Rudi (Mark Blenyesi), his resentful ex-wife Ana (Macrina Bârlădeanu) and Csilla, a passionate, kind-hearted bakery manager and cello player (Judith State) whom Matthias has an undefined sexual relationship with. He never says he actually “loves” her although he keeps returning to her home for solace and whatnot.

Secondary characters include the bakery owner, Mrs. Denes (Orsolya Moldován), and the local priest, Papa Otto (Andrei Finți), and a sizable gathering of anxious, agitated citizens who are basically the local reps of the Mississippi Burning club.

I was going to throw a little snark by alluding to Gene Wilder’s description of the townspeople of Blazing Saddles — “Simple people, people of the land, common clay…you know, morons.”

Except they’re representative of millions of native Europeans right now who are clearly unsettled by Middle Eastern immigrants who’ve been taking root and are changing the traditional character of what they’ve always regarded as “their” culture and homeland.

Xenophobic nationalism reps an un-Christian way of thinking and behaving, to put it mildly, but…I don’t know what to conclude except that it’s fundamentally cruel. Nonetheless this kind of rightwing pushback is manifesting all over. Make of it what you will.

That’s all I need to say. R.M.N. and particularly that town-hall scene are going to reside in my head for a long time to come.

** The English language term is MRI.

*** The film was mostly shot in Rimetea.

During this morning’s Triangle of Sadness presser, director Ruben Ostlund and costar Woody Harrelson announced they’ll reunite for a film called The Entertainment System Is Down. Great news, but there’s a better title to be discovered.

Unasked Ostlund questions: (a) what is your sense of the woke-terror climate at this time? Is it thriving, gaining, receding?; (b) out of all the thousands of splendorful super-yachts in the world, how did you happen to rent the Christina O, which Aristotle Onassis owned in the ‘60s and ‘70s?; (c) to what extent (if any) was Swept Away in the writing of Triangle of Sadness?

Cannes critics have lost their minds over Charlotte Wells’ Aftersun, a laid-back, edge-of-boredom, fly-on-the-wall father-daughter vacation flick, set in Turkey sometime in the late ‘90s. I didn’t mind it and it’s not a painful endurance test, but it’s certainly lethargic as fuck.

Where’s the pulse? Where’s the intrigue or story tension or the proverbial second-act pivot or any of that stuff? Sorry, Jose.

11 year old Sophie (Frankie Corio) and her young-looking, divorced dad (Paul Mescal) are staying (bonding) at a midrange coastal hotel. Swimming pool, video games, camcorder footage, puppy love, golden sunlight, distant hazy forests, dad grinning like an idiot. etc.

A dozen or so little things “happen” (including a curious weeping scene and a mystifying moment when Sophie succumbs to the romantic advances of an overweight gamer) or are more precisely observed. but the whole time you’re thinking “Guy Lodge and Carlos Aguilar did backwards somersaults over this?“

Ruben Ostlund‘s Triangle of Sadness is often wickedly funny — there’s no denying that. Now and then the press crowd at the Salle Debussy was chortling, guffawing and even howling. Even I, a confirmed LQTM-er, laughed out loud five or six times.

The 140-minute Triangle turns broad after the first hour or so, and that’s when it starts to lose the satiric mojo. (But not entirely.) But until that tonal shift it struck me as the funniest, scalpel-like social comedy I’ve seen since…well, now that I think of it, Ostlund’s The Square (’17), which sliced and diced your elite, politically terrified, museum-culture wokesters.

When the capsule synopsis for Sadness appeared online a couple of years everyone immediately recognized the similarity to Lina Wertmuller‘s Swept Away (’74), a Marxist comedy about a luxury yacht sinking and leaving a rich bitch (Mariangela Melato) and a common crewman (Giancarlo Giannini) stranded on a desert island.

Once their class-based loathing of each other fades away, Melato and Giannini fall in love and the social dynamic reverses itself — Melato swooning with desire for the primitive Giannini and vice versa. But when they’re finally rescued Melato reverts to haughty form, leaving Giannini heartbroken.

But strictly speaking the resemblance applies only to Triangle of Sadness‘s third act, titled “The Island.” And it’s different from the Wertmuller (a two-hander) in that Ostlund’s is an ensemble piece.

The first act, focusing on a young, beautiful, somewhat conflicted couple living on modelling and social-influencer income (Harris Dickinson, Charlbi Dean), is titled “Carl and Yaya”.

The film’s best scene occurs early on. It involves a dispute Carl and Yaya have about who will pay for dinner in a pricey restaurant. Yeah, I know — what kind of dude is Carl if he’s expecting Yaya to play the traditional man’s role? But Yaya, who makes a good deal more money than Carl, pledged the night before that she’d cover it, only to blithely ignore the check when the waiter places it on their table. Carl wants them to be equals, he complains, and not submit to standard gender roles. Yaya replies that it’s “unsexy” to talk about money. Manipulation translation: She wants him to get the check anyway.

The second best scene is the opener — a cattle call for a group of shirtless male models (Carl among them) who are asked at one point to show their Balenciaga face (cold, indifferent) and their H&M “happy” face.

In the second act, “The Yacht”, Carl and Yaya are guests on a swanky, first-class vessel (actually Aristotle Onassis and Jackie Kennedy‘s Christina O), and about halfway through this section Triangle of Sadness tips over into coarse slapstick with a healthy serving of gross-out humor a la Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life.

The vomit scene is when the movie changes its game, and while the remainder of the film is amusing in fits and starts, it never qui recovers.

But half of a brilliant comedy (complemented by a reasonably decent one in the second half) is enough for me.

The abundantly wealthy passengers on the cruise (Vicki Berlin, Henrik Dorsin, Jean-Christophe Folly, Iris Berben, Dolly De Leon, Sunnyi Melles) are all vulgar exploiters of one stripe or another. The most amusing tuns are from Woody Harrelson as the ship’s captain — a droll, Marxist-slogan-spouting alcoholic — and Zlatko Burić, a fat Russian fertilizer tycoon (“I sell shit”).

“Find out the movies a man saw between the age of ten and fifteen…which ones he liked, disliked… and you would have a pretty good idea of what sort of mind and temperament he has [as an adult].” — Gore Vidal, Paris Review interview, 1974, as excerpted in David Thomson’s “The Whole Equation.”

It goes without saying that Vidal’s remark applies to women also.

Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to list a dozen or so films you saw and loved between 10 and 15, and then answer whether Vidal was on to something or not. No biggie. Take your time.

For what it’s worth, some of the films I loved during my late-tweener-to-mid-teen period were seen on TV — The Public Enemy, Gunga Din, The Best Years of Our Lives, King Kong, etc. I could go on and on about theatrical favorites of my miserable youth but I have a screening to catch.

On 7.19 Kino Lorber will issue a 4K “special edition” Bluray of Delbert Mann‘s Marty (’55). It will include the correctly framed 1.37 version, which Kino issued in 2014, along with an 1.85 version — a political concession to the 1.85 fascists who screamed bloody murder over the boxy.

In a 7.28.14 HE post titled “Marty Is Boxy After All…Glorious!,” I included an explanation from Kino Lorber vp acquisitions and business affairs Frank Tarzi:

“We looked at [Bob Furmanek]’s research and then screened Marty at 1.85, and didn’t like what we saw,” he said. “If I cropped some of the close-up scenes down to 1.85 I would be cropping half of their face off. I could see [going with] 1.66 but I still think 1.33 is better. We got attacked on Home Theatre Forum and Facebook. I couldn’t believe the tone of [some of the posts]. For a two-week period we were being crucified.”

Tarzi says he’s “very happy” with the boxy Marty. “1.85 just would have been too severe, he believes. “We did several tests. There’s one closeup scene in which Marty’s is on the phone, asking the girl for a date…by the time the camera stops getting in tight, the face covers the whole frame. Cutting that down to 1.85 would have been incorrect.”

Today’s trio: Riley Keough’s War Pony (2:15 pm), Ruben Ostlund’s Triangle of Sadness (4:30 pm) and Cristian Mungiu’s keenly anticipated R.M.N. (10 pm).

Didn’t like and therefore haven’t mentioned — Arnaud Desplechin’s Frere et Soeur, Jerzy Skolimowski’s EO.

Can’t wait for Sunday afternoon’s screening of Ali Abbasi ‘s Holy Spider.

On the Cannes red carpet for George Miller’s new movie, the woman in front of me stripped off all her clothes (covered in body paint) and fell to her knees screaming in front of photographers. Cannes authorities rushed over, covered her in a coat, & blocked my camera from filming pic.twitter.com/JFdWlwVMEw

— Kyle Buchanan (@kylebuchanan) May 20, 2022

“Maybe childhood makes you sad sometimes, but there are other solutions besides ‘hand me the dick-saw.’I’m sure the vast majority of parents do not take this lightly, and [know] that it’s very hard to know when something is real or just a phase. Being trans is different — it’s innate — but kids do have phases. Gender fluid? Kids are fluid about everything. If kids knew what they wanted to be at age eight, the world would be filled with cowboys and princesses. I wanted to be a pirate. Thank God nobody scheduled me for eye removal and peg-leg surgery.” — from last night’s “New Rules” crescendo of last night’s Real Time with Bill Maher.

Edited Twitter reaction: You can’t say George Miller‘s Three Thousand Years of Longing isn’t trippy or eye-popping or CG-swamped or…okay, a bit florid. But it also touches bottom with a poignant, imaginative and very adult current of romance, discovery and even transcendence.

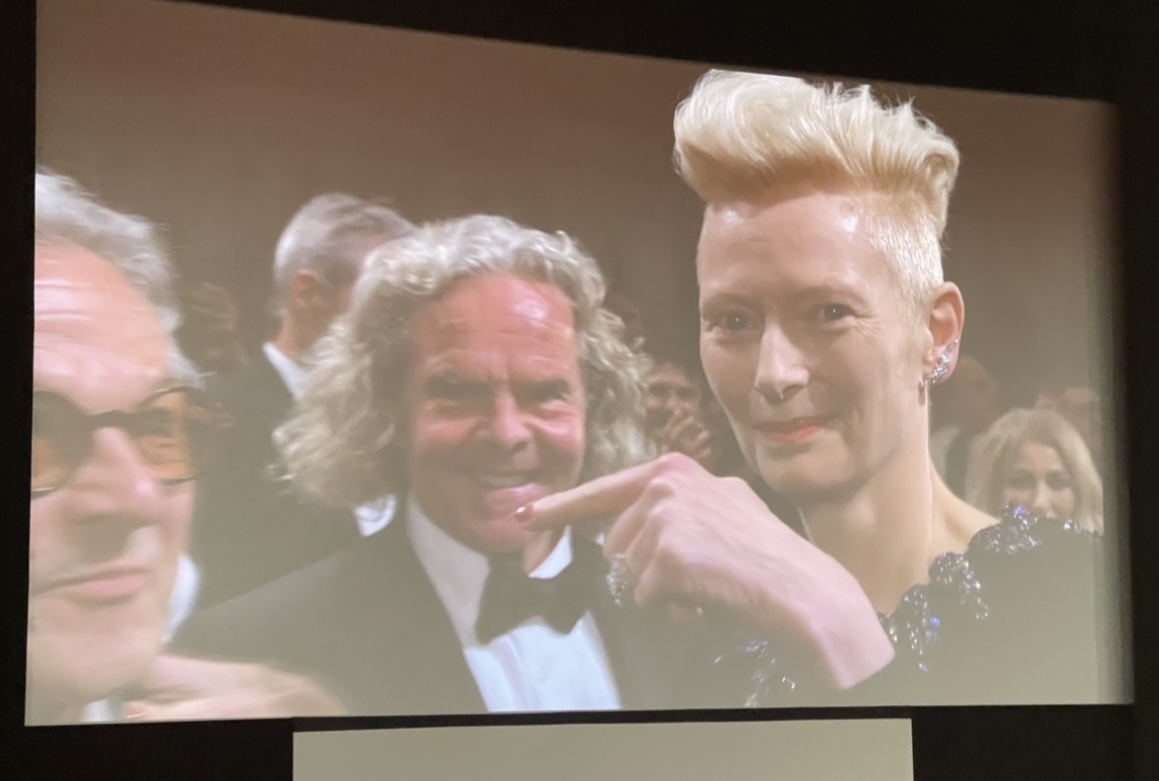

Much of Miller’s film is invested in a 21st Century CG-meets-Michael Powell and The Thief of Baghdad aesthetic, but it’s framed by a very unusual and touching love story between Tilda Swinton‘s English writer — whipsmart, spinsterish — and Idris Elba‘s hulking and thoughtful Djinn (i.e., magic genie).

I can’t say that Longing is a supreme G-spot experience — too much is submerged in the Djinn’s fantastical history, which is devoid of story tension — but the film has something of real emotional value while Swinton and Elba are holding the screen.

I was praying that the film wouldn’t stay inside the genie bottle and smother us with CG fantasy mush.

But during the last 15% or 20% it leaves the CG palaver behind and focuses on the grown-up love story, which is one of the gentlest, most other-worldly and spiritually driven I’ve ever experienced.

Elba** and Swinton are wonderful — seasoned, grounded, playing-for-keeps actors at the peak of their game.

I was scared at first, but Longing turned out much better than I expected. A mixed bag with an intriguing beginning and a payoff that feels (or felt in my case) sublime.

** Elba’s gentle and reflective genie reminded me, of course, of Rex Ingram‘s Djinn in The Thief of Baghdad (’40). What a contrast between this exuberant, rip-roaring, loin-clothed giant and Ingram’s quiet, tradition-minded “Tilney” — servant to Ronald Colman‘s Supreme Court nominee in George Stevens‘ The Talk of the Town (’42).

Friday, 5.20 — 6:45 pm: I’m sitting in the rear left section of the Grand Lumière for a 7 pm black-tie screening of George Miller’s Three Thousand Years of Longing. I scored a last-minute ticket through friends, and I’m the only guy not wearing a tux. Miller, Idris Elba, Tilda Swinton, producer Doug Mitchell on red carpet as we speak.

I regret reporting that Marie Kreutzer‘s Corsage, which screened at 11 am this morning, didn’t sit well. I found it flat, boring, listless. The Austrian empress Elizabeth (Vicky Krieps) is bored with her royal life, and the director spares no effort in persuading the audience to feel the same way.

Krieps plays up the indifference, irreverence and existential ennui. Somewhere during Act Two a royal physician recommends heroin as a remedy for her spiritual troubles, and of course she develops a habit. I was immediately thinking what a pleasure it would be to snort horse along with her, or at least during the screening.

Corsage is unfortunately akin to Pablo Larrain‘s Spencer and Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette — stories of women of title and privilege who feel alienated and unhappy and at a general loss. I’m sorry but this movie suffocates the soul. In actuality Empress Elizabeth was assassinated at in 1898, at age 51. For some reason Kreutzer has chosen to end the life of Krieps’ Elizabeth at a younger point in her life, and due to a different misfortune.

This is one of the most deflating and depressing films I’ve ever seen.