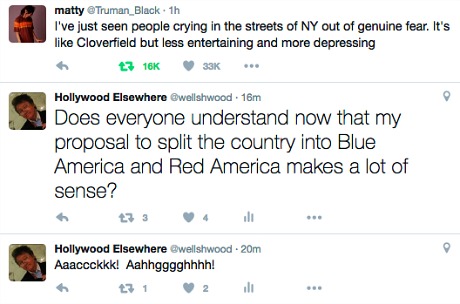

This is what Young Americans are really good at. Coast to coast howls. I feel so proud right now. So much better than grief. No peace, no quarter, no reprieve. Street action in NYC, Boston, Portland, Oakland, San Francisco, Los Angeles, etc. Me? I was watching Robert Zemeckis‘s Allied in Westwood. Better than what I expected — a fine, crafty, old-fashioned suspenser. Great integrated FX. A gold standard movie-movie. Will there be anti-Trump L.A. protest tomorrow night? I’m there.

Today is all about mourning for lefties. I just tried to persuade two female industry pallies (a producer, a cinematographer) to join me for an industry screening of Robert Zemeckis‘s Allied, and they both said they feel too devastated, too depressed to attend. The dp’s voice sounded hoarse and crackly, like she’d just talked herself out of dropping a handful of seconals. The producer sounded more spirited, but she couldn’t rouse herself. Sitting through an entertaining World War II thriller seemed a bridge too far. So there are a lot of depressed people in this town. And I’m wondering how, if at all, this will affect the response to Allied? Hundreds of people who’ve just come from a funeral, sitting in a theatre and staring at a big screen. Their minds elsewhere. Zombies.

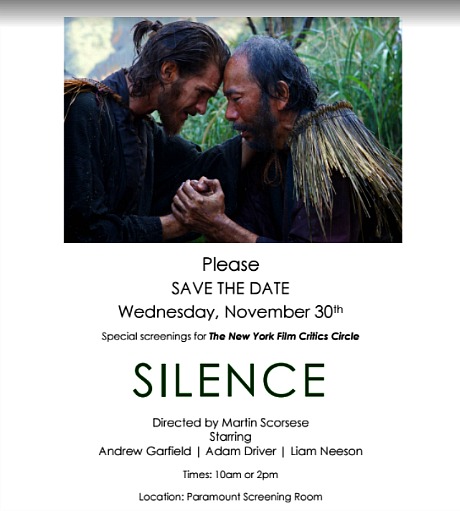

1:15 pm Update: “Things change,” Variety‘s Kris Tapley has just reported. “Paramount is now planning to screen Martin Scorsese‘s Silence for members of the National Board of Review on 11.19 and members of the New York Film Critics Circle on 11.30.” What about the Broadcast Film Critics Association then? If the NBR gets to see Silence on 11.19, the film could surely be shown to the BFCA before the balloting deadline of 11.28. I know that BFCA honcho Joey Berlin was talking to Paramount earlier today.

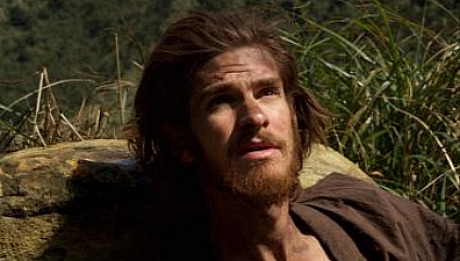

Earlier: When Variety‘s Kris Tapley reported yesterday morning that Martin Scorsese‘s Silence wouldn’t be screening for critics until sometime in December, the assumption was that Scorsese needed more time to fine-tune his period epic. Because to screen it in time for the NYFCC, LAFCA, National Board of Review and the Broadcast Film Critics Association voting deadlines, Silence would have had to be finished and screenable by around Thanksgiving, but Scorsese, one assumed after reading Tapley’s story, needed an extra week or two.

Then I reported this morning that NYFCC members were invited on 10.31 to an 11.30 screening of Silence, which would have at least fit within the NYFCC voting schedule. I assumed after reading Paramount’s invitation that Scorsese had recently changed his mind about the film’s post-production schedule and that the 11.30 screening would no longer be possible.

But an hour ago an Indiewire piece said that that Silence will be screened to 400 Jesuit priests in Rome sometime in late November. So it’ll obviously be finished and screenable later this month. Why, then, are Paramount and Scorsese declining to screen it for critics until sometime in December? It’s apparently not a logistical decision but one based on….you tell me. This is an odd way to play their hand.

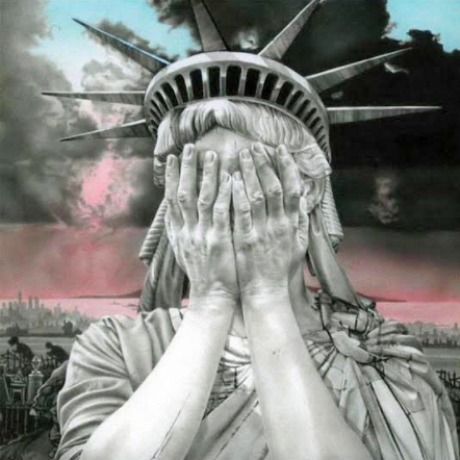

Yesterday’s election was not an “intramural scrimmage.” It was a grotesque smothering of hope. There is no earthly reason to expect that Donald Trump‘s inability to focus on anything for more than a couple of minutes will suddenly change. There’s no reason to expect that he’ll approach the Presidency with anything approaching curiosity, much less competency. What is absolutely certain at this stage is that the Clinton loyalists within the Democratic National Committee have to be jettisoned. Here’s to the mid-terms and a seriously progressive Democratic candidate running for president in 2020.

If Joe Biden had won the Democratic presidential nomination last summer, he’d be president-elect this morning. I’m even telling myself that if Bernie had won the nomination he might have prevailed because at least he was addressing the same anger that Trump managed to exploit so well. The liberal instinct right now is to lower our voices, show a little tenderness, easy does it. The wife of a journalist colleague told me this morning to be extra-gentle with over-45 women today (i.e., don’t be an asshole). Thanks, wife of journalist colleague! But I can sense the mood as well as she can. Whatever grief is being felt this morning by over-45 women, I feel it also. Not “theirs” but “ours.” The fact is that too many Democrats and Millenials stayed home. The bumblefucks didn’t exactly say “no” to a would-be woman president, but they sure as hell said “no” to Hillary.

"The terrorists have won." — Keith Olbermann pic.twitter.com/CCrbWRDCxa

— GQ Magazine (@GQMagazine) November 9, 2016

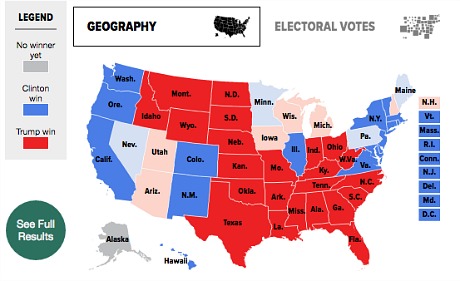

On 7.31 The Young Turks’ Cenk Uygur predicted a Trump win by nearly the same electoral college margin that he actually won by. Michael Moore was predicting the same around the same time, actually a bit earlier. Oh, and by the way? Nate Silver needs to get out of town and hide out in the hills of western Massachusetts until things calm down.

Early this morning HE commenter “Bad Hat Harry” addressed big-city liberal-progressive types about last night’s election result: “I hope you’ve set aside a health does of hate for yourself because you share AT LEAST as much blame for President Trump as anyone who voted for him — your party and policies created the necessary conditions for his ascendency. But of course instead of rational self-examination and reflection, you’ll demonize your opponents and call them names and misrepresent their motives. Easier to let yourself off the hook that way.”

To which I responded: “This is what some voices were saying in the wake of the ’00 and ’04 elections — respect the Bubba vote, respect their motives and concerns. On top of which Bush is a nicer, more personable guy than Gore or Kerry — a guy you can have a beer with. And he’ll stand up to terrorism!

“I was never super-delighted with Hillary Clinton either, but my God…what have they done? The bumblefucks have just taken a giant, self-pitying, anti-progressive shit on this country. They have guaranteed the continuance of Citizen’s United, hastened the demise of the planet through climate change, ensured the rightwing leanings of the Supreme Court and all but stabbed the progressive movement in the heart. They can’t see beyond their own myopic mythology, their own chosen blindness. May their lives only get worse. Much, much worse. May fresh poison flow through their veins. If I could clap my hands three times to ensure this, I would clap my hands three times.”

Early yesterday Variety‘s Kris Tapley reported that Martin Scorsese‘s Silence won’t screen until sometime in December. (I popped in the word “early” in my reaction piece as I assumed they wouldn’t dare wait until mid or late December.) Tapley was no doubt handed legit information by a Paramount source before filing, but on 10.31 — 10 days ago — members of the New York Film Critics Circle received invites to see Silence on Wednesday, 11.30. Specifically a 10 am and 2 pm screening at Paramount’s screening room in Times Square. At the very least Tapley’s story represented an abrupt reversal in strategy because, as the screen-captured PDF invite makes clear, as of 10.31 Scorsese and Paramount were confident that the film would be satisfactorily completed and ready to screen for elite NYC-area critics by 11.30. This would have still gotten in the way of the Broadcast Film Critics Association initial nomination deadline (initial ballots have to filled out by 11.29), but an 11.30 screening date would have probably been finessable. [The below invite was forwarded to me this morning by a NYFCC member.]

9:56 pm Pacific: It’s over. Hillary Clinton, who has lost fair and square, needs to concede — everyone needs to turn off their TVs and take long walks or maybe hit the nearest bar, so she just needs to man up and face the music. She isn’t making things better by stalling. She needs to concede and announce that a bigot, a hatemonger and a guy with an ADD condition that would choke a horse will be sworn in as President on 1.20.17. It’s 1 am in New York. This country just elected an intemperate child, a grotesque clown, to lead the country for the next four years. Ingmar Bergman‘s Shame. The ghost of John F. Kennedy is disgusted. Abraham Lincoln isn’t even reachable.

Nate Silver at 9:50 pm Eastern: “It’s very hard for Clinton to win the Electoral College if she loses Michigan along with Ohio, North Carolina and Florida, none of which look particularly safe for her right now. Even if she were to hold the test of her firewall and win Nevada, she’d be stuck at 263 electoral votes and would need to do something unexpected like flip Arizona or Georgia into her column.”

Nate Silver forecast bot (10:12 pm Eastern): “Clinton wins New Mexico. Our model now gives her a 60% chance of winning the election.” Bullshit! I just took a percocet. Hillary Clinton has been a lousy candidate all along, and now, God help us, the chickens have come home to roost. Thank you, Jill Stein and Gary Johnson supporters. Michael Moore‘s Michigan will go for Trump, and that’s all she wrote.

Thank you, James Comey!

7:42 pm news bulletin: A friend who’s been a hardcore Hillary supporter all along just told me she thinks I’m partly responsible for Clinton’s loss (because I said she’s unappealing as a candidate with the braying and the eye bags), and so she just told me we’re done as friends. Brilliant!

Earlier: Things are looking very tight, and I for one am white-knuckle terrified. Democrats are very nervous. Trump is going to win Florida and quite possibly North Carolina. The bumblefucks are heavily motivated. I’ve been saying all along that my seat-of-the-pants intuition was telling me that Hillary Clinton will squeak through to a victory, but only by a little-mouse squeak. 7:15 pm update: I’m getting a very bad feeling right now — very bad. A reality TV star and an ADD-afflicted demagogue is going occupy the White House.

The hinterland dumbfucks are a lot stronger than anyone figured. If Hillary doesn’t win Florida (and she won’t), it’ll makes HRC’s path to victory a lot tougher. I can’t believe this. A warm-nostril-breath psychopath may actually become President. Not likely but not unlikely either. Terrifying. The Young Turks‘ Cenk Uygur is the prophet. Nate Silver, from whom I drew endless comfort during the campaign, has some splainin’ to do.

Earlier today Variety‘s Kris Tapley reported that Martin Scorsese‘s Silence won’t screen until sometime in early December, which means that the screening deadlines of the National Board of Review, NYFCC and LAFCA (i.e., the New York and Los Angeles critics’ orgs) and HE’s own Broadcast Film Critics Association are being ignored. Which is too bad as these four groups will definitely be selecting the 2016 award season hotties, and now Silence is looking at…well, it’s own path.

At least this puts the Hollywood Foreign Press Association in a good spot to elevate Silence (or not), as they’ll be voting a bit later in December.

This isn’t a tragedy but it’s too bad that Scorsese has decided that Silence will be a latecomer. (Glengarry Glenn Ross‘s Shelley Levene says “lately kiss my lately.”) If I were Marty I would say “fuck it” and screen an almost-cut to these four groups and then invite them to see the final, fussed-over version later in the month. How different could these two versions be? A few trims, a few music cues.

As a voting member of the BFCA, may I make a suggestion? Cut Marty some slack by offering him a special dispensation in their voting procedure. Silence won’t be seen when initial BFCA balloting begins on the morning of 11.28.16 and ends on 11.29.16. And yes, the BFCA noms will be announced on 12.1.16. But the final BFCA ballots will be e-mailed on 12.8.16 with return ballots required by 12.9.16 by early evening.

But the BFCA (which, don’t forget, cut J.J. Abrams‘ Star Wars: The Force Awakens a huge break last year) could simply decide to include Silence sight unseen on the final ballots, and then if Silence is screened by, say, 12.5 or 12.6, the membership could see it and vote accordingly. Where would be the harm? Bend over for Marty, guys! He’s earned a special measure of respect.