Any thoughts you may have had about Jerry Bruckheimer and Joseph Kosinki‘s Top Gun: Maverick possibly dealing subtle cards and not necessarily using sledgehammer tactics are now…well, let’s just say that hopes along those lines are temporarily dashed. If this just-released teaser is any kind of indication, I mean.

San Diego-based fighter pilots!….the aura of studly military rock stars, coping with buried anger and the burden of expectations, brusque and strapping and throwing their heads back in laughter while playing piano in a honky tonk. (Like Miles Teller‘s son of Goose Bradshaw character does in a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it clip.) And the women who both love and compete with them. With the big climactic test of skill and character looming. And so on.

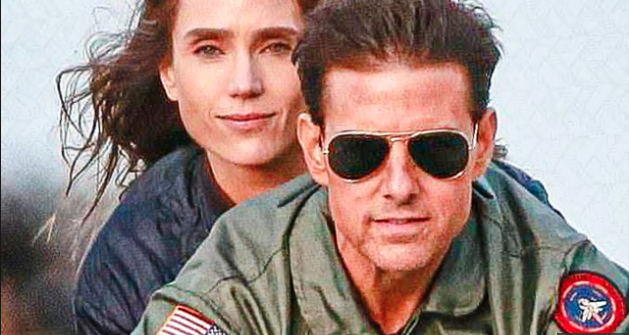

I haven’t read the script (co-authored by Peter Craig, Justin Marks, Christopher McQuarrie and Eric Warren Singer) but the tip-off is a Wikipedia description of Jennifer Connelly‘s character — “a single mother running a bar near the Naval base.”

A single mother! Running a bar! Who dispenses sage advice while mixing a killer Mojito! With, I’m guessing, a possible age-appropriate interest in Tom Cruise‘s Maverick, who’s now a creased and weathered Naval flight instructor. And perhaps, in keeping with the theme of launching the new generation, with an aspiring fighter-jock daughter? Or am I pushing too far?

I want a scene in which Cruise tells Connelly that Kelly McGillis‘ Charlie Blackwood left him for another woman, and then (beat, beat) Connelly tells Cruise, “Yeah, I know…it was me.” Or: “I’m sorry, that’s tough. (beat) She left me too.”

Ed Harris to Cruise: “Captain…what is that?” Jon Hamm playing some kind of tough nut. And Val Kilmer back for seconds. All the young dudes of the original Top Gun are now in their late 50s and early ’60s.

Best shot in the trailer: Crew-cutted Cruise riding a motorcycle without a helmet, bathed in magic-hour amber, loving the wind and grinning the grin.

Cruise’s six career-best roles (in this order): (1) Vincent the assassin in Collateral, (2) the titular Jerry Maguire, (3) Joel Goodson, the U-boat commander of Highland Park, (4) Charlie Babbitt in Rain Man, (5) Ron Kovic in Born on the Fourth of July, and (6) Frank T.J. Mackey in Magnolia. Honorable Mention: Mitch McDeere in The Firm.