Tip of the hat to Slashfilm‘s Peter Sciretta for posting this work-priint version of an alternate ending to Alexander Payne‘s Election, etc. Horrible!

Daily

Cards Up

If Terrence Malick could somehow swing it, I’m sure, The Tree of Life wouldn’t be about to screen in 70 minutes’ time. (It’s now 7:20 am.) However good or great or whatever it turns out to be, there’s a certain satisfaction in one of the most prolonged hiding-from-the-world acts in modern cinematic history about to come to an end. I briefly discussed it last night with a friend. Friend: “So how sucky is the Malick going to be, do you think?” Me: “It might not be what some want, but it can’t suck — it’s Malick.”

You Lose

Earlier today I tried to catch a 5:15 pm screening The Snows of Kilimanjaro at the Salle Bazin. This is what I saw when I arrived 15 minutes before showtime. I went to the end of the line and stood and waited and stood and waited. I knew I’d never get a seat but I toughed it out to the end. And then I said “eff it” and got on the train to Juan-les-Pains.

Silver Train

Late this afternoon I took a quick ride between Cannes and Juan-les-Pains, except the train decided not to stop at Juan-les-Pains and dropped me off at Antibes instead. So I impulsively asked Sasha Stone and her daughter Emma to join me there, and we had a pretty good time detoxing and sipping rose and roaming around the marina area and contemplating the Picasso museum exterior.

Antibes

The Picasso museum in Antibes, which is about a half-hour east of Cannes by local roads.

Looking east toward Nice — Sunday, 5.15, 7:20 pm.

Reasons Why

Any and all theories about why Paul Feig and Judd Apatow‘s Bridesmaids exceeded expectations this weekend to earn an impressive $24.4 million are hereby requested. The expectations were between the low teens and $16 or $17 million. So what happened? Was Saturday Night Live‘s” Kristen Wiig the big selling point? The girlie poo-poo humor? Or what? And what were the gender and age breakdowns?

The film’s B-plus from Cinemascore is a result of it not being a start-to-finish laugh riot so it’ll probably drop at least 40% next weekend, but still…

"But Not Out Here…"

Here’s an excellent analysis of John Ford‘s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance by N.Y. Times critic A.O. Scott. Spoiler whiners are hereby advised that Scott reveals the third-act secret in this 49 year-old film.

Shuffle

The Artist costars Berenice Bejo, Jean Dujardin at this morning’s Cannes press conference.

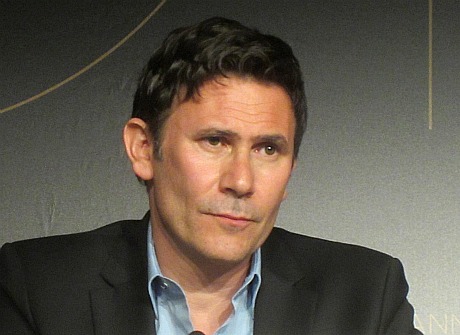

The Artist director Michel Hazanavicius — Sunday, 5.15, 11:25 am.

Return star Linda Cardellini (l.), costar Louisa Krause (I think) prior to last night’s showing of Liza Johnson’s film about a female soldier’s difficulty in adapting to home turf after serving in Iraq.

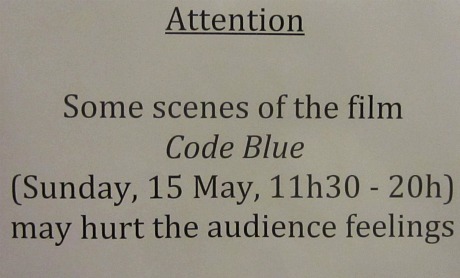

This is one of those unfortunate translations. The original French caveat was probably something about Code Blue being possibly traumatic for some.

Days of Wop Rock

Two days ago Deadline‘s Michael Fleming reported that Ryan Gosling will star in and direct a remake of Taylor Hackford‘s The Idolmaker (’80). Gosling will be playing Ray Sharkey‘s role, I presume, which was based on rock-music promoter and manager Bob Marcucci.

The first two-thirds of The Idolmaker are brilliant. It’s probably my favorite Hackford film, closely followed by Against All Odds. Marcucci discovered and managed Frankie Avalon and Fabian, among others.

The Artist

Michel Hazanavicius‘ much-anticipated The Artist, which just finished showing in the Grand Lumiere, is a winning “success,” and at the same time a half-and-halfer — a film that delivers beautifully but also leaves you wanting in certain ways. It’s a black-and-white silent drama with dashes of humor (i.e., I wouldn’t call it a dramedy) that’s first and foremost a tribute to the lore and sheen of 1920s Hollywood. And that much is fine.

If you’re any kind of film buff it’ll work for you and then some, but I’m not so sure about the under-45 set. Monochrome plus no dialogue are obviously stoppers for the majority of filmgoers out there. Let’s face it — The Artist would have seemed like a quaint exercise if it had been made 35 or 40 years ago by Peter Bogdanovich.

My basic impression is that The Artist is a very well-done curio — an experiment in reviving a bygone era and mood by way of silent-film expression. Is it a full-bodied motion picture with its own voice and voltage — a film that stands on its own? Not quite. But it’s a highly diverting, sometimes stirring thing to sit through, and the overall HE verdict is a thumbs-up.

The Artist has been very carefully assembled, but chops-wise it’s not strictly a revisiting of silent-film era language. It visually plays like a kind of ersatz silent film — technically correct in some respects but with a 2011 sensibility in other ways. It has a jaunty, sometimes jokey tone in the beginning, and then it gradually shifts into drama and then melodrama. But it tries hard and does enough things right that the overall residue is one of satisfaction and “a job well done.”

Shot in Los Angeles, the story of this French-financed production recalls the plots of Singin’ In The Rain and A Star Is Born with a little Sunset Boulevard thrown in.

It takes place in Hollywood between 1927 and 1931 and focuses on George Valentin (Jean Dujardin) a Douglas Fairbanks-y silent film star who stubbornly refuses to adapt to the advent of motion-picture sound, and Peppy Miller (Berenice Bejoa), a Janet Gaynor-like or young Joan Crawford-y actress whose career takes off with sound.

Hazanavicius uses an entire passage of Bernard Herrmann‘s Vertigo score in the final act, when Valentin is at his lowest ebb.

It’s interesting that Dujardin strongly resembles Fredric March, star of King Vidor‘s A Star Is Born (1937). It’s doubly interesting that Dujardin apparenty gained weight for the role, as his appearance today (i.e., in the press conference inside the Palais) is definitely slimmer.

John Goodman plays a studio chief, James Cromwell plays Valentin’s chauffeur, and Penelope Ann Miller plays Valentin’s unsatisfied wife.

From the Wiki page: “Director Michel Hazanavicius had been fantasizing about making a silent film for many years, both because many filmmakers he admires emerged in the silent era, and because of the image-driven nature of the technique.

“According to Hazanavicius his wish to make a silent film was at first not taken seriously, but after the financial success of his spy-film pastiches OSS 117: Cairo, Nest of Spies and OSS 117: Lost in Rio, producers started to express interest.

“The forming of the film’s narrative started with Hazanavicius’ desire to work again with actors Jean Dujardin and Bereenice Bejo, who had starred in the OSS 177 films. Hazanavicius choose the form of the melodrama, partially because he though many of the films from the silent era which have aged best are melodramas.

“Filming took place during seven weeks on location in Hollywood. Throughout the shoot Hazanavicius played music from classic Hollywood films while the actors performed.”

Respectable But Minor

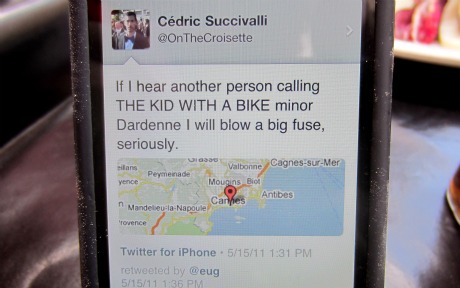

Jean Pierre and Luc Dardenne‘s The Kid With The Bike, which I saw early Saturday evening, is being reflexively praised here and there because (a) it’s a low-key but entirely competent teenaged kid-desperate-for-paternal-support film, but (b) mainly because the Dardennes are highly respected big wheels within the Cannes journalistic community.

If The Kid With The Bike had been made by an unknown younger director and shown under Un Certain Regard or Semaine des Critiques, positive reviews would result — it’s an honest, well-made film — but it wouldn’t cause much of a stir.

Believe me, The Kid With The Bike is nothing to do mad cartwheels over. Yes, the Dardennes are first-rate scenarists and straight shooters; they know exactly what they’re doing every time. And their film ends well. But Cannes critics are, I feel, kneeling forward and kissing the proverbial ring. There’s nothing wrong with that in a general sense as long as there’s perspective.

Yes, I took an instant dislike to Thomas Doret, the red-haired lead character called Cyrill, when I first saw the trailer. This feeling deepened when I saw the film. I disliked his obstinate-woodpecker personality and the dogged, loon-like tone in his voice. If I ran into a kid like this in real life I would excuse myself fairly quickly, you bet.

Honestly? While the decision of his youngish kitchen-chef dad to abandon Cyrill and go his own way because he has very little money is reprehensible and pathetic, on a certain level I sympathized. Some men are just weak or selfish or naturally un-gifted at parenting (like my own dad), and some kids are just irksome. My heart goes out to any kid dealing with parental neglect and/or abuse, but on the other hand life is hard and sometimes cruel. Some of us are dealt shitty cards, but we have to play them as best we can.

Cyrill, it’s clear, is emotionally damaged and heading for some kind of downward swirl, perhaps into crime or becoming an abuser on his own. So on one level it’s admirable when a kind-hearted, fair-minded hairdresser named Samantha (Cecile de France) agrees to become Cyrill’s weekend care-giver, but on another level it’s a bit…puzzling?

She’s expressing a standard maternal instinct, but I found it curious that a youngish, attractive woman’s life would be so otherwise bereft of passion and commitment that she would leap into this kind of relationship. And I found her willingness to suddenly dump her somewhat selfish-minded, not-especially-bright boyfriend when he says “it’s him or me” too abrupt.

I felt that the whole film was a bit too simplistic and on-the-nose. I went with it, but I also felt that I was being fed a plate of honest but under-cooked contrivances by a couple of talented but (this time around) under-inspired chefs.