The banner headline on the March issue of Empire, which has been on sale for three weeks, teases “The Greatest Cinema Moments Ever.” Which, of course, is bullshit. The actual content (37 pages) could be more accurately described as “Edgar Wright‘s Favorite Mindlowing Holy-Shit Movie Moments Over The Last 20 Years.”

The epic journey of cinema from the dawn of the sound era to New Year’s Eve 1999 is pretty much ignored. But that’s the Empire readership for you — the ’90s are the good old days, memories of the ’80s are fading fast and anything before the Ronald Reagan era is Paleozoic. That’s Wright for you also — a 46 year-old director who knows all about the 20th Century landscape (and all the joy, pain, anxiety, struggle and exhilaration of that convulsive century) but who thinks about movies only in terms of (a) bang-boom-pow-CG-fizz-whizz for movie nerds and more specifically (b) “Jesus, that was so fucking iconic!” and (c) “My God, that was one fucking kewl adrenaline rush!”

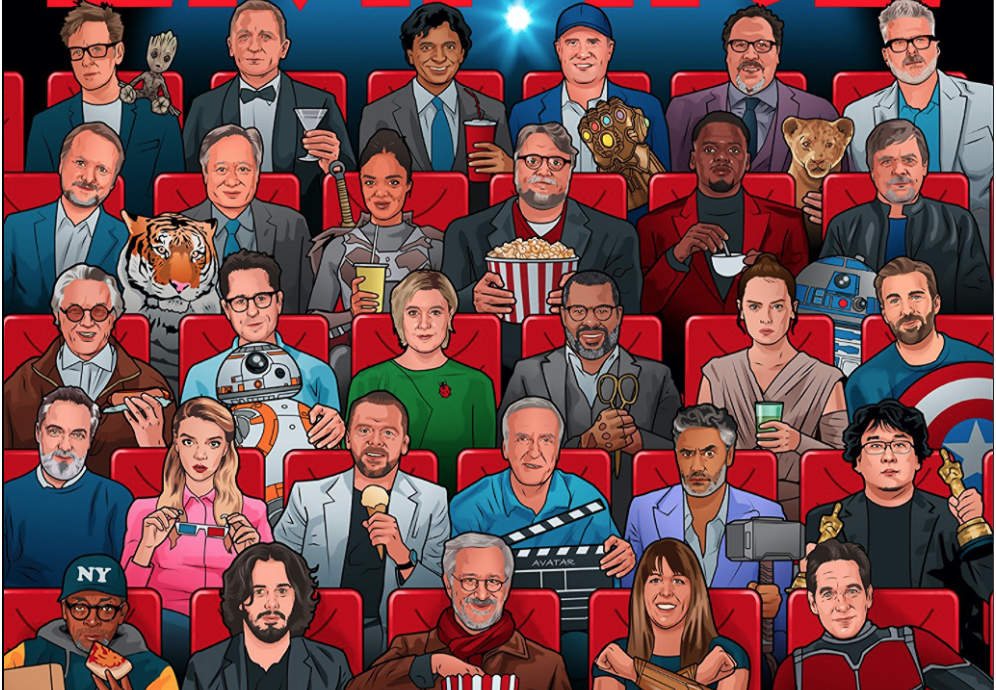

The cover faces are said to include Steven Spielberg, Tessa Thompson, Patty Jenkins, Jordan Peele, Taika Waititi, Paul Rudd, Guillermo del Toro, Chris Evans, Simon Pegg, Daniel Kaluuya, M. Night Shyamalan, Kumail Nanjiani, George Miller, Greta Gerwig, Kevin Feige (pronounced FAY–gee), Christopher McQuarrie, Joe Russo, J.J. Abrams, Bong Joon-ho, David Yates, Daisy (“Cary who?”) Ridley, Joe Cornish, Anya Taylor-Joy, James Gunn, Bill Hader, Alfonso Cuarón, Walter Hill, Rian Johnson, Spike Lee, James Cameron, Lily James, Robert Zemeckis, Ang Lee, Jon Hamm, Daniel Craig, Jon Favreau, Sam Mendes and Mark Hamill. But maybe not.

HE takes exception to the notion that Spike Lee, a serious scholastic movie buff, would watch a film within a packed house (remember packed houses?) while eating a greasy pepperoni pizza. Forget the Do The Right Thing reference — is there anything more rancid than stinking up the joint with the steamy smell of heated pepperoni while chewing and slurping and smacking his lips? I’m not kidding — only animals eat pizza during a film.