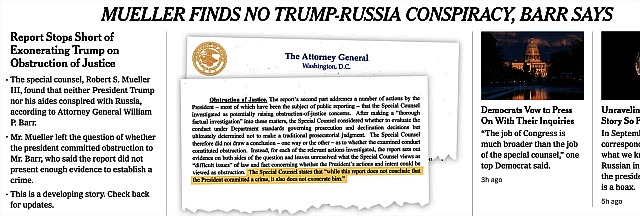

I’m disappointed. Make that damn disappointed. What semi-intelligent, fair-minded person wouldn’t be?

It seems to me that in observing the precise letter of the law and drilling only into possible proof of an actual, real-deal conspiracy to undermine the 2016 election by colluding with Russian operatives, Robert Mueller has seemingly sidestepped the basic overall, which is that President Trump is a malignant narcissist, an amoral sociopath and the head of a New York crime family, and that he doesn’t give a shit about anyone or anything other than his own empowerment and/or his mushroom dick being sucked. And that before and after 1.20.17 he’s acted this way to the detriment of the country and that portion of the population (i.e., a two-thirds majority) that respects the law and various concepts of human decency.

Michael, a N.Y. Times commenter, posted a few minutes ago: “I’m not surprised absent a written directive from Trump, a recorded phone call, or someone close to the president willing to tell the truth under oath, that Mueller could not prove obstruction of justice or criminal conspiracy inside the campaign.

“However, as Barr and Mueller state, this does not exonerate him. There is too much circumstantial and incriminating evidence surrounding the president’s firing of Comey, the many meetings between the Trump campaign and Russian operatives, to say ‘no collusion, no obstruction.’

“It was a huge mistake not to interview Trump under oath. I believe after the full report is issued, Congress needs to continue its oversight role that has only just barely begun. Important facts are waiting to be uncovered.

“This isn’t about optics — it’s about determining the integrity and/or duplicity of the man holding the highest office in the land.”

Laura, another Times commenter: “I’m just shocked. There’s no other word for it. As an avid follower of this whole sprawling Russia story over the last 2 years, I just don’t see how this is possible.

“There is just so much wrongdoing is plain sight — how can this be the outcome?

What about the Trump Tower meeting? And Kushner wanting to establish a back channel to Russia so US intelligence couldn’t listen to their conversations? And Trump trying to fire Sessions for not recusing himself? And the dozens of other examples of things just as corrupt, suspicious, and possibly illegal??

“Is Barr covering up for Trump? I don’t really think that, but it’s sort of the best idea I can come up with at the moment of why this is happening.